Computed tomography and acute stroke

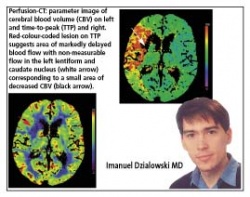

By Imanuel Dzialowski MD

´CT has been revolutionizing the understanding and treatment of stroke´ - that is the summary of Dr. Dzialowski.

In February 2005 Dr Imanuel Dzialowski became a Postdoctoral Fellow, on the Calgary Stroke Programme, at the Department of Clinical Neurosciences, in Foothills Hospital, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, following a wealth of neurology and neuroradiology training, experience and stroke research in the University of Technology, Dresden, the Humbold University, Berlin, and the University of Essen.

He is also co-author of a dozen papers/abstracts, printed in the publications Radiology, Intensivmed, Stroke, Journal of Neurology, Cerebrovascular Diseases, Aktuelle Neurologie, Journal of Neuroimaging.

Patients with an acute stroke syndrome present with hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, hemianopia, speech disturbance, or impairment of consciousness. The two most common causes are cerebral ischaemia and intracranial haemorrhage. Less frequent differential diagnoses include migraine, seizure, cerebral venous thrombosis, focal encephalitis, demyelination disorder, or tumour. Brain imaging is necessary to assess the exact diagnosis and the acute pathophysiological state of the brain. Both will guide treatment and will finally determine the patient’s clinical outcome.

Computed tomography (CT) has been revolutionizing the understanding and treatment of stroke since its introduction into clinical practice around 30 years ago. Magnetic resonance imaging is another upcoming imaging modality with even greater potential to study the brain in acute stroke. However, it is not yet widely available in most countries and its feasibility in severely affected patients is still limited.

Despite the enormous progress CT has conveyed, stroke scientists must ask whether its use really improves patients’ outcomes. Kent and Larson proposed five levels of clinical efficacy for assessing diagnostic technology: 1) technical capacity 2) diagnostic accuracy 3) diagnostic impact 4) therapeutic impact, and 5) patient outcome. This article addresses the question of which pathology CT is able to assess in patients with acute stroke; how accurate this information is; and whether imaging with CT has any impact on stroke diagnosis, stroke treatment, and finally on the clinical outcome of patients.

Technical capacity of CT in acute stroke

Based on changes in X-ray attenuation, non-contrast CT is capable of detecting the following changes:

> Intracranial haemorrhage appears clearly hyperdense, e.g. as parenchymal mass or filling of the subarachnoid space

> Thrombo-embolic arterial occlusion; well-defined hyperdensity in the course of the middle cerebral artery

> Ischaemic brain oedema; hypodensity of grey or white matter manifesting e.g. as ‘loss of cortical ribbon’ or obscuration of the lentiform nucleus.

Adding intravenous contrast media, CT can assess intracranial vessel status (CT angiography, images 4 and 5) and brain parenchyma perfusion (perfusion-CT, image 6).

Diagnostic accuracy

Because CT was the first modality that could image the brain in-vivo, a reference standard for CT findings in acute stroke has seldom been available. However, surgery or autopsy regularly confirms the CT finding of intracranial haemorrhage.

In cerebral ischaemia, hypo-attenuation on CT is highly specific for irreversible brain tissue damage. In its very early stage, ischaemic oedema might be too subtle to be detected by the human eye. However, even within three hours from symptom onset, CT is positive in about 40-60% of patients.

CT has diagnostic impact by reliably differentiating between haemorrhagic and ischaemic stroke. In addition, it is used to differentiate among types of cerebral ischaemia like territorial infarcts caused by emboli, infarcts in end-supply areas or ‘watershed areas’ often associated with major artery occlusion or stenosis, and disseminated small infarcts caused by small vessel disease.

Therapeutic impact

For the first time in history, CT enabled identifying patients suffering from cerebral ischaemia. As a consequence, specific treatment like thrombolysis could be tested. CT has thus an enormous therapeutic impact just by differentiating between ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke.

In acute cerebral ischaemia, the only treatment that is proven to improve clinical outcome is intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) applied within three hours of symptom onset, or intra-arterial infusion of pro-urokinase in patients with MCA occlusion if applied within six hours of symptom onset. In selected patients, the time-window for intravenous thrombolysis can be extended to up to six hours from symptom-onset and CT identifies those patients at risk for thrombolysis-related secondary intracerebral haemorrhage.

In acute haemorrhagic stroke, prothrombotic treatment with Factor VIIa appears to be a therapeutic option in the near future.

Impact on patient outcome is the most important criterion for the usefulness of a diagnostic test showing that it leads to a change in patient management that improves patient outcome. CT enables thrombolytic therapy and thereby reduces likelihood for disability by at least 30%. Each prevented disabling stroke saves estimated life-time-costs of around US$90,000.

In summary: CT is the current standard of care in acute stroke since it impacts stroke diagnosis and therapy and thereby improves patient outcome.

02.08.2006