Article • Computer intelligence

Cognition-guided surgery – a rocky road

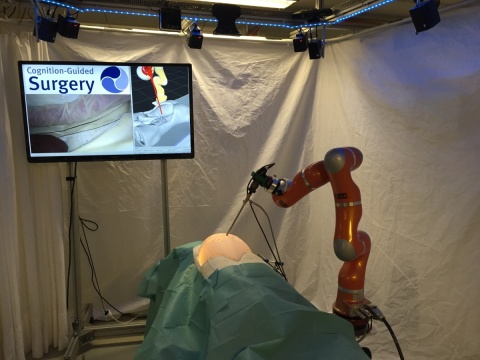

Surgery will change – with all the challenges that developments such as Big Data create there are no two ways about it. However, how deep those changes run remains to be seen. In a rather young field of research, scientists look at the ways all components used during surgery can be interlinked. Professor Beat Müller, co-initiator of the project ‘Cognition-Guided Surgery’, explains results achieved so far and coming challenges.

Report: Marcel Rasch

Cognition-guided surgery aims to enable surgeons to make knowledge-based computer-aided decisions during surgery – with the help of computers. This requires the creation of a database that is filled with factual and practical knowledge that a machine can process and use.

The underlying idea is for a surgeon to be able to call up suitable actions when planning or performing an intervention. ‘You can compare it to a cognitive vehicle. While we are in the car driving along the road we often don’t notice that there are technologies in the background that control traction or chassis or whatever. When problems occur, a warning is displayed. As an advanced development, the cognitive car is autonomous, entirely disconnected from the human driver,’ Professor Beat Müller explains.

The human brain can process or access a maximum of about seven pieces of information at a time. However, large amounts of data are not a problem for a computer. The challenge for the machine is not data volume but data interpretation. ‘In surgery we are dealing with massive data volumes. Every day, new knowledge is published in thousands of books and articles, new insights are culled from diagnostics, which is an increasingly complex discipline. A few decades ago X-ray images were all we had; today we are looking at CT and endoscopy images, at lab and histology parameters previously unknown.

‘To collect these data and channel them into a sound decision – that’s the complex art of medicine. Unfortunately humans do make poor decisions every once in a while. Thus cognition-guided surgery wants to create a system that helps to make good decisions.’

Initial results

That’s a long way to go. It won’t suffice for scientists to access Big Data and to design analytical tools; they must consider a very special factor, as Müller points out: ‘The ability to learn is a crucial feature of the machine. The computer must be able to process not only factual knowledge, or book knowledge, but also practical knowledge gathered over time in the course of our everyday work. All these types of knowledge are input for the knowledge base. What we are aiming at is a system that does not suggest certain procedures anymore, because of the negative outcomes this procedure yielded in the past. Instead the system suggests only procedures with a higher probability of success.’

Such a system might indeed work, as was demonstrated by an initiative funded by the German Research Fund (DFG) between 2012 and 2016. ‘In the special research area Cognition-Guided Surgery, teams from a consortium of researchers, including the German Cancer Research Centre and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, looked at several key aspects of this idea,’ Müller reports. In the course of the project an adaptive autonomous camera-guidance robot was developed. ‘When the computer correctly guided the camera during an intervention, this experience was stored as “positive”. But when the camera-guidance robot was corrected, it stored the correction,’ he explains. Thus the system learns the correct camera positions step by step.

The road ahead

There is enormous potential to make surgery safer and more efficient.

Prof. Beat Müller

However, many challenges lie ahead. ‘Don’t forget – we are at the very beginning of our research,’ says Müller, dampening unrealistic expectations. ‘On the one hand we have to make the required data available in a machine-compatible way. When, as trained physicians, we look at an X-ray image and can read it – we understand what we are seeing. The more X-ray images we read, the more we learn. The computer must also go through this phase of gathering experience and knowledge.’ On the other hand, Müller explains, ‘a computer can easily do statistical analyses, but semantic assessments are a major obstacle. We are talking about model-based or pattern-based action. It’s not only about gathering data but about the way these data are perceived and evaluated.’

A third difficulty is system validation. ‘The computer has to show that its suggestions, which are based on the learning process, are indeed better. Human beings learn from success and failure. Machine learning happens in smaller increments. If an error made by the system is not corrected, the system will store it as “positive”, no matter whether there might have been specific reasons for not correcting the error in this particular case. In short: We must ensure the system not only gathers knowledge but that it indeed improves. Poor approaches to learning might very well lead to poor therapy suggestions. And the worst-case scenario is that we don’t even realise that the surgeon performs worse with computer aid than without it,’ Müller warns.

Despite these caveats, the vision is alive. ‘There is enormous potential to make surgery safer and more efficient,’ Müller believes. However, today there are only a few isolated solutions and there are not enough research partners for large interdisciplinary research projects. ‘However, if we look at cognitive vehicles again, there are market-ready solutions claimed to be safer than human drivers. This is what I’d like to achieve for surgery.’

Profile:

Professor Beat Müller MD, a leading senior physician and Head of Section for Minimally Invasive and Bariatric Surgery at the Department for General, Visceral and Transplantation Surgery at Heidelberg University Hospital, also researches computer-based surgery. He has been lead investigator in several interdisciplinary and multi-partner research projects such as ‘Intelli¬gent Surgery’ and ‘Cognition-Guided Surgery’ (both underpinned by the German Research Fund (DFG) until 2014 and 2016 respectively. Beat Müller is also a key participant in InnOPlan (Innovative, Data-driven Efficiency of Surgery-related Process Landscapes), a project funded in the framework of the technology programme ‘Smart Data – Innovations from data’ by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, and the EU-funded project COMBIOSCOPY (Computational biophotonics in endoscopic cancer diagnosis and therapy).

Further information:

http://www.cognitionguidedsurgery.de+http://rob.ipr.kit.edu/837_1586.php

14.11.2016