Cancer stem cells

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are the engine that drives tumour growth. They can not only reproduce themselves but also differentiate to form all the specialised cells found within a tumour. While chemotherapy and radiotherapy non-specifically target all rapidly dividing cells, there is increasing evidence that CSCs are more resistant to these treatments.

Report: Karoline Laarmann

Thus, if targeted treatment can be devised to work specifically against CSCs, it might be possible to eradicate a cancer completely as well as prevent its later recurrence. ‘It’s like trying to weed a garden,’ reflected Dr Trevor Yeung, a surgeon-in-training and clinical scientist from the Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, Oxford University, UK: ‘It’s no use just chopping off the leaves; we need to target the roots to stop the weeds from coming back.’

At this year’s ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology) Cancer Biology Symposium, to be held in Nice, France on 26 & 27 November, Dr Yeung’s lecture will focus on CSC – fact or fiction?

So, what indeed are CSCs? ‘Part of the problem is that the terminology may be confusing and evocative, especially the phrase stem cell,’ he said, during an interview with Karoline Laarmann. ‘A better term would be cancer-driving cell. Nevertheless, whatever we call these cells, there is overwhelming evidence that different subpopulations of cancer cells exist, and that it is the CSC subpopulation that drives tumour growth.’

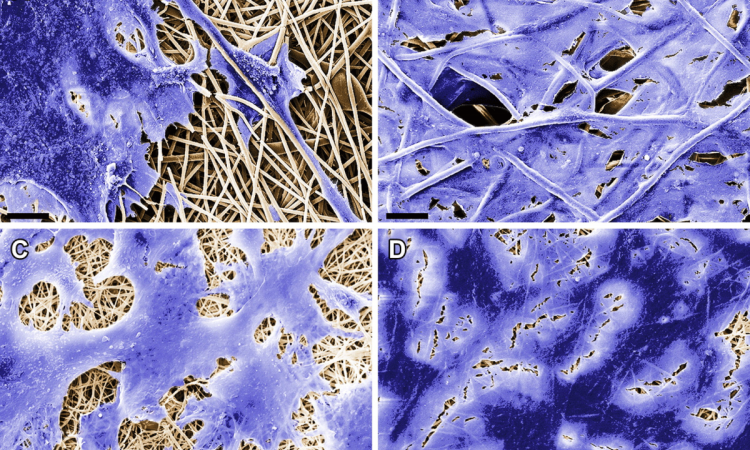

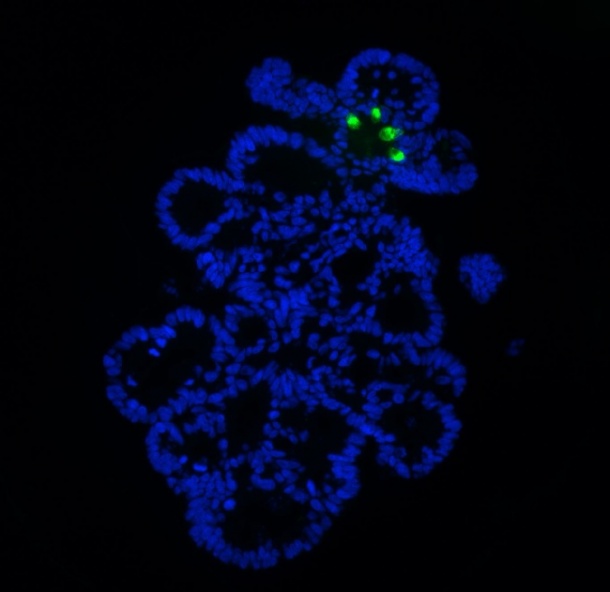

Dr Yeung is a member of an Oxford study group headed by Professor Sir Walter Bodmer that developed a new way of cultivating CSCs samples in the lab that should greatly accelerate its study and allow the development of drugs targeted against them.* Previous cancer stem cell work has relied on cancer biopsies obtained from patients, which is labour intensive and may not be easily repeatable. The Oxford team developed a new technique to enrich these cancer stem cells in the laboratory using established cell lines; this will enable high throughput testing of drugs that may be more specific for CSCs.

Because the technique makes it much easier to work with cell line material and gain more of it than with fresh tumour tissue, the technique also enables greater analysis of stem cell functions. Furthermore, better in vitro cell culture methods might help to reduce the use of animals for preclinical evaluations of drugs. ‘CSCs may express different surface proteins to the non-CSC population, so this may provide another mechanism of attack,’ Dr Yeung said. ‘A further potential method would be to attempt to induce differentiation of these CSCs so that they are no longer able to self-renew and drive tumour growth. Current developments are at an early stage, so it may take many years before such a drug is available for patients.’

“The pharmaceutical industry is extremely interested in cancer stem cell research and is actively engaging with us to investigate new ways to target them,’ Dr Yeung said. ‘With regards to personalised treatment, such treatment is already widely practiced for cancer e.g. administering Herceptin only for Her2+ breast cancer, not giving anti-EGFR treatment to patients with Kras mutations in colorectal cancer, Gleevec for CML and GIST.’

Several groups across the globe are researching different aspects of CSCs – for example, how best to identify them, how they behave in a tumour, and how to develop new therapies to target specifically them.

Conferences such as the ESMO Symposium naturally allow medical researchers to share ideas and form new collaborations. ‘Clinician scientists are in a unique position to be able to translate basic biological research into benefits for clinical practice,’ Dr Yeung added.

*Cancer stem cells from colorectal cancer derived cell lines. Yeung TM, Gandhi SC, Wilding JL, Muschel R and Bodmer WF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Feb 23;107(8):3722-7.)

03.11.2010