Image source: Shutterstock/GagliardiPhotography

Article • Mammacarcinoma screening

Breast cancer: Simply monitoring might be best

Breast cancer screening is a well-designed and scientifically proven, evidence-based procedure, but has pitfalls such as under-detection and over-diagnosis. Surgery or radiotherapy may have serious consequences on health and must therefore be administered in carefully selected patients.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

Research is ongoing as to how screening can help differentiate between the cancers that deserve treatment from those that don't, a British expert told delegates during ECR 2019.

Screening is effective and helps save millions of patients with breast cancer (BC) annually – but it is not without flaws, and can trigger a chain of actions that may cause more harm than doing nothing. In some cases, it might be best to monitor the disease than to treat it right away, according to Matthew Wallis, a breast screening radiologist and researcher in Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Treatment has side effects

Treatment is not risk free, Wallis explained. ‘I’ve been working in breast screening for rather more years than I wish to remember and I firmly believe I’ve done more good than harm. But, there are probably women out there who have received more treatment than was strictly necessary and probably have had harm as a result of my interference, and not just the bruises I cause when I do vacuum biopsies, ‘he said.

Cancer is a very complicated process and personalised care is much more than just the oncologist prescribing more and more expensive drugs for fewer and fewer people but very targeted. ‘It is also reducing what radiologists do at the lower end scan,’ Wallis said. Cancer is highly complex and requires different approaches depending on the patient and her disease. ‘With breast cancer, we’re still very fixated on this multistep progression based on epidemiology and morphology and it’s been a very good thing. Actually the molecular and genetic basis of this is much more complicated,’ he said.

Long treated as a single disease process, the medical community is shifting away from that. ‘Treatment has changed: we’ve moved from appalling surgery to mastectomy, to partial mastectomy, to local mastectomy, to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In the UK, some women are not even offered treatment at all for their axilla. We used to rip everything out, then a little out, and now there’s nothing,’ he said.

Knowing when and when not to treat could reduce side effects of current treatment, which range from death from catastrophic sepsis to lymphoedema, chronic pain and musculoskeletal symptoms. Avoiding treatment when unnecessary would also spare women burdening cosmetic and psychosocial consequences that may drastically impact on their health and quality of life.

BC screening still falls short in distinguishing between cancers that should or should not be treated, i.e. differentiating low risk from high-risk cancers. ‘We pick them all up. That’s because our targets for screening are about cancer detection and not about detecting killing cancers,’ Wallis explained. ‘Matching high-risk disease biology with chemotherapy is now possible, but it’s still tricky to identify biologically low risk cancers and that probably wouldn’t need the full game of treatment like chemo, radiation therapy and surgery. Since those cancers probably would not develop or kill anyone in their normal life expectancy.’

Differentiating low and high-risk cancers is improving

We need to be out there explaining these women that cancer is an enormous great house of lots of different things and some are bad news and some are good news

Matthew Wallis

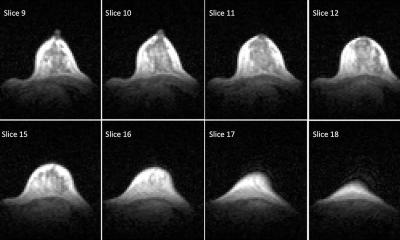

Low risk DCIS can now be spotted early with mammography and confirmed by biopsy; it might never become cancer and if it does, it would do so much later on in life. It might be more interesting to offer active monitoring than immediate treatment for these conditions, according to Wallis. ‘The risk of these DCIS is so low that some people would like to reclassify them as indolent breast lesions or idle lesions, rather than calling them cancer. DCIS can be detected with imaging potentially 10 to 15 years before they present clinically, which would leave plenty of time to assess if a lesion turned cancerous or not,’ he pointed out.

Other low risk cancers exist and need consideration, as they could benefit from active monitoring, i.e. by performing mammography once a year. Three international randomised controlled trials are currently looking specifically at active monitoring vs. surgery for low risk DCIS: the LORIS (The LOw RISk DCIS trial), LORD (LOw Risk DCIS) and COMET (Comparison of Operative versus Medical Endocrine Therapy for Low Risk DCIS) trials, each with a 900-patient cohort.

In the UK, the PRIMETIME trial will tackle invasive cancers that can potentially spread over the breast. ‘We’re offering women aged over 60 with small, low risk cancers to opt in to radiotherapy or opt out, with the anticipation that radiotherapy is unlikely to offer them any benefit,’ Wallis said. The SMALL trial, also in the UK, will follow 850 women aged over 60 with tiny low-grade invasive cancers over five years, after offering them the opportunity to be treated with vacuum biopsy and subsequent radiotherapy, vs. surgery and radiotherapy.

‘It’s about avoiding unnecessary treatment. Should we re label these cancers? I don’t know,’ he said. ‘I’m not sure just changing the box to include more or less is necessarily a good idea. We need to be out there explaining these women that cancer is an enormous great house of lots of different things and some are bad news and some are good news. And if it’s good news, you can live with it in symbiosis and we’ll follow you and if it gets worse,’ Wallis concluded. ‘We’ll sort you out and your survival will still be the same.’

Profile:

Matthew Wallis has been a breast screening radiologist since 1989. After 19 years as director of breast screening in Coventry, Warwickshire and Solihull, he moved to Cambridge to concentrate on research – with a major research interest in using routinely collected data to optimise all aspects of breast screening from the imaging chain to surgical management. His other interest is DCIS and de-escalation of treatment. He is also chief investigator of LORIS, the Low Risk DCIS trial.

01.12.2019