Autologous cartilage transplantation

Advances in the treatment of cartilage injuries to the knee are very noteworthy. The decisive breakthrough must have been the development of the self-resorbing, bilayer collagen membrane (Chondro-Gide) by Geistlich in Switzerland.

This allows the damaged area and replacement material to be covered long enough for the new tissue to integrate and heal.

Sports-related knee injuries often lead to concomitant injuries of the articular cartilage. However, in adults, articular cartilage damage has literally no tendency at all to self-heal. Left untreated, over the years they lead to an increasing destruction of the joint (arthrosis), and there are always efforts to find new means to avoid this. During a discussion with European Hospital, Professor Matthias Steinwachs MD (above) at the Schulthess Hospital in Zurich, a leader in the latest developments, outlined some of those techniques.

Operative treatment procedures

With arthroscopic drilling (Pridie procedure) and the procedure of microfracture drill holes are inserted into the bony base of the cartilage damage, leading to bone marrow leaking out and then clotting within the damaged area and settling as a fibrin clot containing stem cells. After 6-8 weeks rest for the joint, a fibrous replacement cartilage develops that, unfortunately, has limited biomechanical characteristics.

Autologous matrix-induced chondroneogenesis (AMIC) is a procedure developed for the treatment of awkwardly situated, large cartilage defects. The bone marrow leaking from the drill holes is retained within the damaged area by covering it with periost or a self-resorbing collagen membrane (Chondro-Gide). However, this also leads only to the development of rather ineffectual fibrous cartilage.

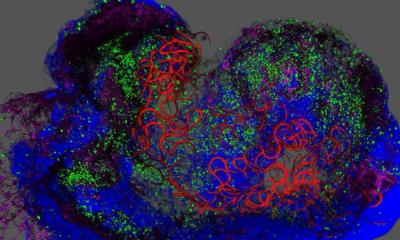

Autologous chondrocyte transplantation (ACI), a biological procedure developed for clinical use a few years ago, involves the removal and subsequent analysis of a small cartilage sample from a non weight-bearing part of the joint during arthroscopy. The cartilage cells are removed from the tissue under sterile conditions and germinated in a Petri dish. Enough cells are cultivated to cover the defect. After 3-4 weeks germination the cells are inserted into the damaged area during an open operation and covered with the collagen membrane. Under these conditions the cells develop a much higher grade regenerated cartilage that has almost 90% of the biomechanical characteristics of healthy articular cartilage. It also means the joint can be used much earlier, significantly shortening rehabilitation.

Chondro-Gide bilayer collagen membrane

Swiss company Geistlich has made a significant contribution to advances in the treatment of cartilage injuries through the development of the new type of collagen membrane Chondro-Gide. This membrane covers the defect and the replacement material used to fill it and holds it in place. In Europe, the previously used periost is now hardly used because all too often the tissue becomes overgrown (hypertrophy) and patients experienced consistent pain requiring further operations. The new collagen membrane decreased these undesired late effects.

Chondro-Gide consists of collagen of porcine origin. The membrane’s compact, smooth outer layer prevents permeation by foreign cells. The porous inner layer consists of collagen fibres that promote cell adhesion and stimulate cell growth. The configuration of the fibers ensures high tensile strength. The membrane can be fixed with fibrin glue, sutures or pins, which prevents it from sliding or displacement resulting from mechanical strain. Spontaneous disintegration of the membrane through resorption takes about 3-6 months.

As Prof Steinwachs explained, in 99% of cases these methods have been used on the knee joint; it is also possible to use them to operate behind the kneecap. ACI has been used since 1988 although, unfortunately, it turned out that the fibrous cartilage that developed lasted only on average for three years. With AMIC plus Chondro-Gide it should be possible to achieve much better results, he said. However, as this procedure has only been used for 3.5 years no conclusive statistics are available yet.

One major problem with this procedure is cost. Surgical costs of ACI and AMIC are about the same and covered by medical insurers. However, with AMIC there is an additional cost to cultivate the cells – around 7,000 Swiss Francs. So far, medical insurers do not cover this. Perhaps, given sufficient data from follow-up studies, this will change.

Literature: MR Steinwachs: The treatment of articular cartilage damage. The Medical Journal (TMJ) 2008;

3: 7-12

28.10.2008