Looking inside

A new method of viewing TB bacteria

Although tuberculosis (TB) is commonly thought of as being a disease that mainly affects nineteenth century poets and Victor Hugo characters, it is still the second-most common cause of mortality from an infectious disease in the world, killing nearly three people every minute.

TB is generally a curable disease—but first it must be diagnosed, and that has been one of the biggest barriers in its elimination. M. tuberculosis grows very slowly, so traditional methods of diagnostic testing take a very long time. A team from the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine has been working on a new approach. The work is led by Jeffrey Cirillo, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Microbial Pathogenesis and Immunology.

Cirillo’s previous research, which has been supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust, has focused on developing a rapid yet inexpensive test for tuberculosis. He and his team have nearly perfected the technology and are in the process of bringing the test to market.

The slow growth of M. tuberculosis also makes development of new therapeutics difficult because it takes so long to determine if the treatment is working.

Now, Cirillo and his team have developed a method of detecting whether a potential treatment is working as early as a day after it is given. “Since M. tuberculosis takes about a month to quantify using traditional approaches, any method that allows direct determination of the amount of bacteria present is very valuable and speeds progress, saving months every time an experiment is done,” Cirillo said. “Our methods allow this.”

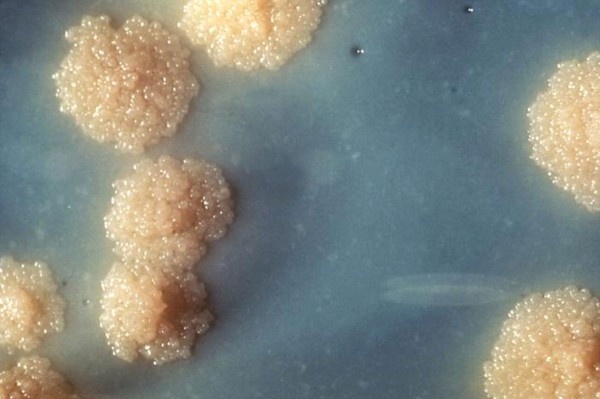

Using optical imaging technology, the researchers can observe the bacteria in real time, in living animals, without harming them. This way, it is easy to determine if a proposed treatment is working and the number of bacteria is decreasing. “There have never been sensitive enough systems to measure the bacteria directly in animals,” Cirillo said. “This is a completely new technology and has nearly limitless applications to microbiological research, particularly in animals, but it increases sensitivity in any experimental system.”

Drug-resistant TB, now present everywhere in the world, is hampering efforts to fight the disease because the usual drugs used to treat it are no longer effective. Therefore, new, more effective treatments need to be developed.

The researchers first had to find the best fluorescent protein to help them visualize the bacteria. “We use very sensitive systems that can actually see the signal through mammalian tissue,” Cirillo said. “This works best in the near-infrared, which is where our signals are primarily produced.”

Active TB causes symptoms such as cough, fever, night sweats, weight loss. If left untreated—a common scenario in developing countries lacking health care infrastructure—a person with active TB has only a 50 percent chance of survival, and he or she will infect an average of 10 to 15 people each year.

“The goal in TB research is complete eradication of the disease,” Cirillo said. “We think this new technology is one tool to do just that.”

Source: Texas A&M University

05.04.2016