Spource: University of British Columbia

News • Additive manufacturing

3D printing testicular cells

In a pair of world firsts, scientists have 3D printed human testicular cells and identified promising early signs of sperm-producing capabilities.

The researchers, led by UBC urology assistant professor Dr. Ryan Flannigan, hope the technique will one day offer a solution for people living with presently untreatable forms of male infertility.

“Infertility affects 15 per cent of couples and male factors are a contributing cause in at least half those cases,” said Dr. Flannigan, whose lab is based at the Vancouver Prostate Centre at Vancouver General Hospital. “We’re 3D printing these cells into a very specific structure that mimics human anatomy, which we think is our best shot at stimulating sperm production. If successful, this could open the door to new fertility treatments for couples who currently have no other options.”

Within human testicles, sperm is produced by tiny tubes known as seminiferous tubules. In the most severe form of male infertility, known as non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA), no sperm is found in ejaculate due to diminished sperm production within these structures.

While in some cases doctors can help NOA patients by performing surgery to find extremely rare sperm, Dr. Flannigan says this procedure is only successful about half the time. “Unfortunately, for the other half of these individuals, they don’t have any options because we can’t find sperm for them.”

Those are the patients Dr. Flannigan’s team is hoping to help.

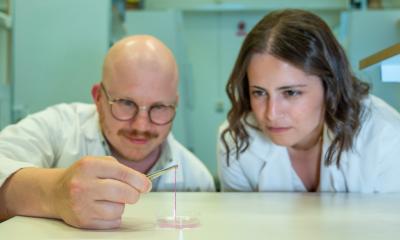

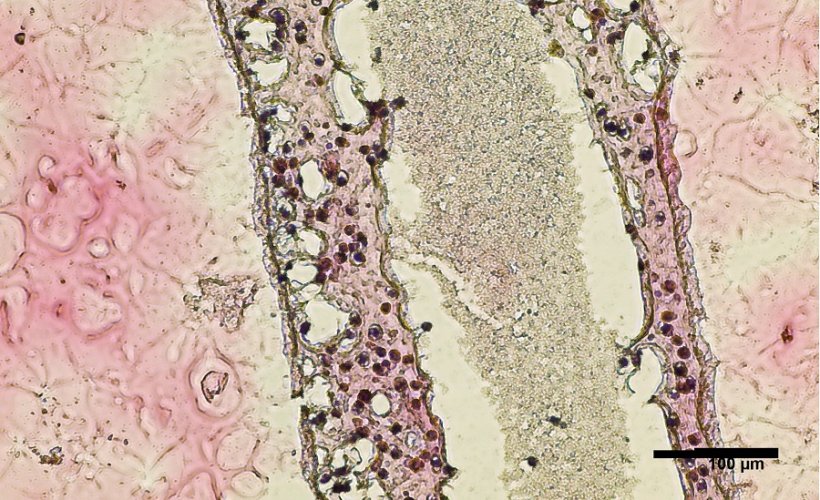

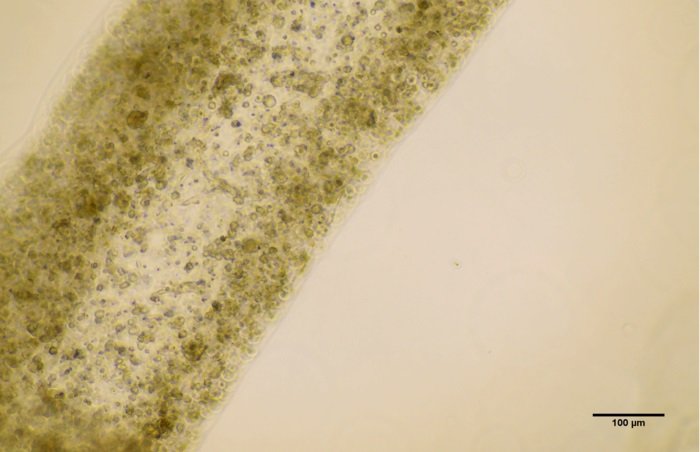

Source: Courtesy of Dr. Ryan Flannigan

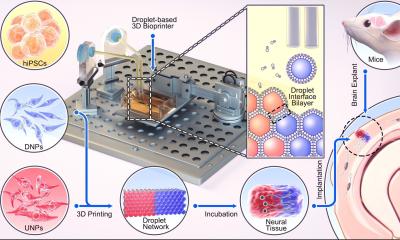

For the recent study, the researchers performed a biopsy to collect stem cells from the testicles of a patient living with NOA. The cells were then grown and 3D printed onto a petri dish into a hollow tubular structure that resembles the sperm-producing seminiferous tubules.

Twelve days after printing, the team found that the cells had survived. Not only that, they had matured into several of the specialized cells involved in sperm production and were showing a significant improvement in spermatogonial stem cell maintenance – both early signs of sperm producing capabilities. The results of the study were recently published in Fertility and Sterility Science.

“It’s a huge milestone, seeing these cells survive and begin to differentiate. There’s a long road ahead, but this makes our team very hopeful,” said Dr. Flannigan.

The team is now working to “coach” the printed cells into producing sperm. To do this, they’ll expose the cells to different nutrients and growth factors and fine-tune the structural arrangement to facilitate cell-to-cell interaction.

If they can get the cells to produce sperm, those sperm could potentially be used to fertilize an egg by in vitro fertilization, providing a new fertility treatment option for couples.

Dr. Flannigan’s research program has also been shedding new light on the genetic and molecular mechanisms that contribute to NOA. They’ve been using various single cell sequencing techniques to understand the gene expression and characteristics of each individual cell, then applying computational modelling of this data to better understand the root causes of the condition and to identify new treatment options. The work has been highly collaborative, involving UBC researchers across computer science, mathematics and engineering, as well as international collaborations.

“Increasingly, we’re learning that there are likely many different causes of infertility and that each case is very patient specific,” said Dr. Flannigan. “With that in mind, we’re taking a personalized, precision medicine approach – we take cells from a patient, try to understand what abnormalities are unique to them, and then 3D print and support the cells in ways that overcome those original deficiencies.”

Source: University of British Columbia

21.03.2022