Article • Abbreviated MRI

Seeking a view through the dense breast

The EA1141 trial

Despite rigorous quality assurance of breast cancer screening programs, ‘both, over- and under-diagnosis of breast cancer is a challenge,’ says leading radiologist Christiane K Kuhl, from the Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, at the University of Aachen, Germany. ‘Mammography is a good screening test – but has its limitations especially, but not only, in women with dense breast tissue. And, since breast cancer continues to represent a major cause of cancer death in women, we have good reason to search for improved screening methods.’

The current established gold standard of breast cancer screening, i.e. digital mammography, is associated with both, over- as well as under-diagnosis of breast cancer. Over-diagnosis means that screening mammograms pick up indolent cancers, which, even if left undiagnosed and thus untreated, would never becomelife threatening. Under-diagnosis means that screening mammograms fail to pick up many aggressive cancers that will, if undetected/untreated, progress to metastatic disease and thus contribute to breast cancer mortality.

The major reason for both over- and under-diagnosis is variable breast cancer biology. ‘Over the past years, our understanding of breast cancer as a heterogeneous group of diseases has greatly increased. Today, breast cancer is characterised by its genomic features. The different molecular subtypes of breast cancer explain the quite variable imaging presentation, risk of progression, response to treatment and patient survival between different breast cancers.’

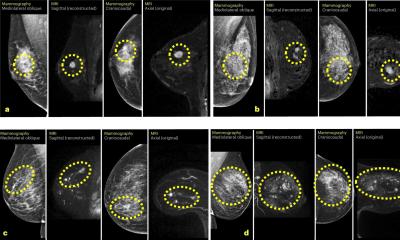

Detection of breast cancer in digital mammography – and also in digital breast tomosynthesis – relies on the depiction of pathophysiological processes that are associated with slowed tumour growth. ‘For instance, we pick up architectural distortions that are caused by tumour hypoxia; we pick up microcalcifications that are caused by tumour cell death. We distinguish malignant tumours from benign ones by morphological features such as spiculations – features that are typical for Luminal-A breast cancers – which are the least aggressive ones.’ Kuhl explains ‘This tells us that mammography is good at finding cancers that are slowly growing – in other words: mammograms have a technology-inherent, and thus unavoidable, bias to detect less aggressive cancers. On the other hand, particularly aggressive breast cancers can exhibit pushing margins, may not cause architectural distortions, and may not be associated with calcifications. Thus, especially the faster growing cancers can remain undetected on mammography until they are large enough to become clinically palpable,’ the radiologist explains.

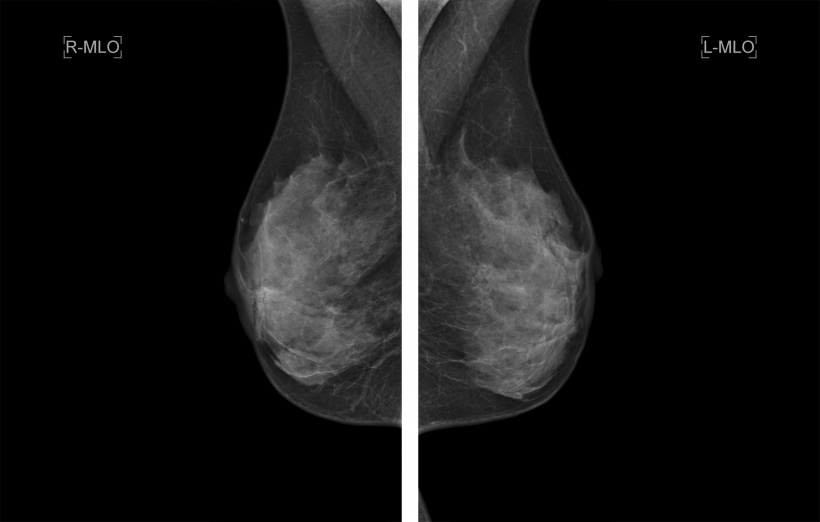

Additionally, there are host-related factors that will modulate the detectability of breast cancer on mammograms. ‘Breast cancers tend to be similarly white on a mammogram compared to normal fibroglandular tissue. Therefore, normal fibroglandular tissue can obscure cancers. The amount of fibroglandular tissue in the breast, or breast “density”, varies greatly between women from none to extremely dense. At age 50, about half of women have intermediately dense or extremely dense breasts that may obscure cancers. Yet, dense breast tissue means not only a reduced mammographic accuracy in finding cancers – but is an established risk factor for developing the disease,’ Kuhl explains. This is why in the USA, women are informed about their individual breast density, and supplemental screening methods are endorsed in women with heterogeneously dense and extremely dense breasts.

The most important advantage of breast MRI compared with mammography is that its sensitivity profile is reversed to mammography

Christiane Kuhl

The concept of all current mammographic screening programs is to offer one and the same method – mammography – for every woman. This is the exact opposite of modern concepts of personalised medicine,’ Kuhl explains. ‘We need screening methods that are tailored to the need of the individual woman in order to avoid both, over- and under-diagnosis of breast cancer.’

Due to the sensitivity profile of radiographic breast imaging per se, the limitations of mammographic screening will only be marginally addressed by using improved radiographic imaging, such as digital breast tomosynthesis. ‘It’s beyond discussion that breast MRI is the most accurate screening method currently available. However, the aim of contemporary breast cancer screening is not to increase the number of cancers detected,’ she emphasises, ‘but to improve, and thus ensure, early detection of biologically important breast cancer – and avoid diagnosis of conditions that will not impact on patients’ outcomes.

‘The most important advantage of breast MRI compared with mammography is that its sensitivity profile is reversed to mammography: Breast MRI is indeed best in finding cancers with adverse biological profile, whereas it may remain normal in women with low-grade DCIS. ‘Breast MRI thus offers the sensitivity profile that does match what contemporary screening is expected to deliver.’

Abbreviated breast MRI

‘Due to the high cost of MRI it is currently reserved for a small group of women who carry a very high breast cancer risk. Yet recent data suggest that even, only a small fraction of this group indeed undergo MRI screening. MRI is not even considered for all remaining women who carry an average to moderately increased risk –despite the fact that breast cancer is the main cause of cancer death in these women, and despite the fact that MRI has been shown to be as advantageous in them as in high risk women. Bottom line: MRI is greatly under-utilised both in high risk and average risk women.

‘With all evidence on the side of breast MRI screening, our main goal now is to improve and ensure access to this life-saving screening test,’ Kuhl says. ‘Since cost is the most important challenge to overcome, we aim to make this test less expensive.’

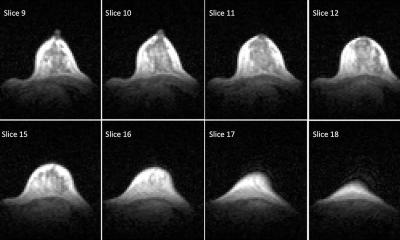

One aspect that drives costs is how MR systems are used. So far, MRI protocols – including those for breast cancer screening – employ complex and demanding technology to interrogate tissue properties to maximum. Therefore, clinical MRI protocols consist of an entire battery of pulse sequences that are time consuming to acquire and read. ‘The concept of abbreviated MRI is to focus on specific components tailored to answer a specific clinical question – and cut out all other components, to keep it simple and short’, Kuhl explains. ‘For MRI breast screening, the question is arguably: Is breast cancer present or not? It takes about three minutes’ magnet time to answer this question but, more importantly, with abbreviated MRI, it takes only a few seconds of radiologists reading time to establish this diagnosis.’

If combined with dedicated MRI systems optimised for breast imaging and which ensure fast patient throughput, ab-MRI could be a viable alternative for population-wide screening.

Christiane Kuhl

Kuhl introduced the concept of abbreviated MRI in her landmark paper published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014, where she showed the abbreviated protocols work perfectly well, and allow breast cancer diagnosis with the same superb sensitivity and specificity typical of a full-protocol, ‘conventional’, multiparametric breast MRI. Since that publication, a number of articles followed by authors in Europe, Asia, and the Americas, which confirmed the reproducibility and clinical utility of this approach

‘The results of all studies so far suggest that abbreviated MRI yields equivalent diagnostic accuracy as does full-protocol MRI, and thus could be a powerful breast cancer screening tool for a wider group of women. ‘However, we need the same measures of quality assurance established, put to practice and enforced that are also part of mammographic screening, before we can even think of offering Ab-MRI on a broader scale. The first step is to test the concept rigorously in a large, multi-centre clinical trialin terms of effectiveness, patient acceptability and cost, against our best radiographic screening modalities, to ensure that it truly can reduce both over- and under-diagnosis.’

Thus, the EA1141 study has been set up (sponsored by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group / American College of Radiology Imaging Network - ECOG/ACRIN). Under the lead of Christopher Comstock, MSKCC, Gillian Newstead, University of Chicago, and Christiane Kuhl, University of Aachen, this study aims to compare abbreviated MRI with digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer screening of dense breasts.

‘If combined with dedicated MRI systems optimised for breast imaging and which ensure fast patient throughput,’ Kuhl concludes, ‘ab-MRI could be a viable alternative for population-wide screening.’

Profile

Christiane Kuhl MD has been Director of the Clinic of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at University Hospital Aachen, Germany, since 2010. After completion of her medical studies, Kuhl was appointed professor at the Department of Oncological Diagnostics and Interventional Radiology at University Hospital Bonn, Germany. As one of the most renowned German breast cancer researchers, the professor explores the benefits of MRI-based early detection of breast cancer. She has received several German and international awards for her work.

25.10.2017