Tissue engineering in paediatric cardiac surgery

When heart valves need replacing mechanical or biological heart valves are usually used. Both have disadvantages: Mechanical prostheses promote the development of blood clots so that patients need anticoagulant treatment for their lifetime.

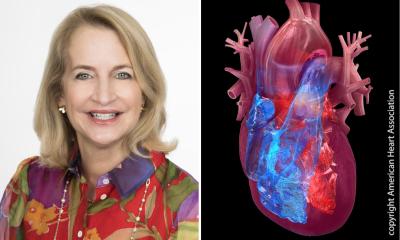

Professor Axel Haverich implanting a growing heart valve

Cardiac surgeons in Hanover, led by Prof. Alex Haverich, have now successfully developed heart valves that can ‘grow’: In the laboratory, all cells are removed from a human donor heart valve until only the tissue ‘frame’, the acellular matrix, is left. In the second step, stem cells from the patient’s blood or bone marrow are ‘settled’ on this frame, and these will grow into tissue cells. After two to three weeks the new heart valve is ready for implantation. Seeing that the method uses the body’s own material there are no issues with tissue rejection and the implant lasts a lifetime.

The objective of the project , which began in 1996 at the Leibniz Research Laboratory for Biotechnology and Artificial Organs (LEBAO), is the development of heart valve prostheses that are the equivalent of natural valves both from a conceptual point of view and from their biological behaviour. The implants must neither be immunogenic nor thrombogenic, but resistant against infections and must be able to grow. After animal tests on small and large animals the first clinical implantations on humans were carried out on seven paediatric patients with heart valve disease, in May 2002 at the Republican Centre for Cardiac Surgery in Chisinau, Republic of Moldova.

Today, after 3.5 years of regular cardiac examinations there are no signs of any aneurysmatic changes, degeneration of the hart valves or stenosis. Moreover, physiological expansion of the pulmonary valve rings has been detected, which is proof of the valves’ ability to grow inside growing children. At the same time, valve function has been preserved unimpaired. ‘From everything we now know, and looking at the latest examination results, I can assume that we will never have to touch these valves again,’ says Haverich. The Hanover-based researchers are now waiting for permission to use the new procedure in Germany as well. In Germany, two out of every 1,000 babies have congenital valvular heart disease. Experts estimate that 150 of those could benefit from the new method.

01.05.2006

More on the subject: