The therapeutic potential of adult stem cells in CVDs

By Professor Bodo-Eckehard Strauer MD, Head of the Department of Cardiology, Pneumology and Angiology at Dusseldorf University Hospital

Cardiac infarction is characterised by tissue ischaemia with loss of contractile heart muscle.

The consequence is cardiac insufficiency and disturbance to cardiac rhythm. About two thirds of all patients have no symptoms before an infarction; about two thirds of all patients do not survive their cardiac infarction. About a third of surviving infarction patients experience increasingly worsening heart function in the first year after the infarction (remodelling).

The aim of therapy is to re-open the infarcted vessel using acute procedures (balloon dilatation and stent implantation), though this is merely the tip of the iceberg and the destroyed heart muscle usually remains useless. This is where treatment with stem cells comes in as causal therapy, striving to regenerate heart muscle by injecting stem cells into it.

The body itself contains naturally occurring, adult autologous stem cells, e.g. in the bone marrow. They are an ethical resource of cells that is completely safe. The idea was therefore to regenerate heart muscle clinically, by transplanting naturally occurring bone marrow stem cells into the infarcted region. This process was developed in Dusseldorf.

Bone marrow was removed and the cells prepared, then, after re-opening the infarcted vessel by balloon dilatation, they were injected into it under low pressure, using a balloon technique. The vessel was kept open with a catheter (a procedure lasting about 30 minutes), during which time two to three ml of a suspension of stem cells were injected into the infarcted region, a process repeated with four to six insufflations. The intervention was carried out on conscious patients with local anaesthesia, and at most produced mild pain at the site of injection.

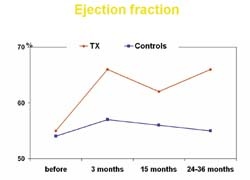

Follow-up controls for three years and longer after the infarction show that long-lasting mprovement in cardiac function has been achieved, with an average increase in cardiac function of 50% and a reduction in the size of the infarct of about 20%. At the same time, blood supply to the cardiac muscle has been considerably improved, as has metabolism, and physical strength has increased. As yet, no side effects have been reported, so the procedure should be considered an ethically safe treatment of muscle loss after infarction, and causal therapy that is really beneficial to the patient.

The Dusseldorf results have since been confirmed worldwide. Work groups in Frankfurt, Hanover and Rostock have been able to show, even in larger studies, that regeneration of infarcted cardiac muscle can be achieved by transplanting autologous bone marrow stem cells. What is important is that this myocardial regeneration, which, depending on study design, is between 4–16%, is of an order of magnitude that is at least as great as the sum of all therapeutic improvements in ventricular function achieved with balloon dilatation or stent implantation for cardiac infarction. Consequently, added improvement in patients’ ventricular function can thus be achieved, on top of surgical intervention and drug treatment.

No complications from the stem cell treatment have been reported so far. There is no malignant degeneration as the cells used occur naturally in the body. No signs of inflammation have been observed, nor have disturbances to cardiac rhythm, angina pectoris or respiratory distress. Complications arising from the procedure itself are much the same as those that might occur in ordinary heart catheterisation procedures, and are insignificant.

It should be mentioned that a similar procedure is also effective in treating peripheral arterial disease. In this case, treatment involves intra-arterial and intramuscular injection of autologous bone marrow stem cells into the limbs affected, the therapy first practised by Bartsch et al. Ischaemic preconditioning, such as by compression induced with a cuff, or even ergometry, greatly promotes migration of stem cells into the muscles.

After three months there was marked improvement in the length of stride, the ankle/arm indexes, oxygen saturation and even venous occlusion plethysmography parameters. Consequently, autologous stem cell therapy can also be classed as a successful procedure for peripheral arterial occlusive disease, where symptoms are refractory to treatment, and in advanced stages of vascular disease.

01.09.2007