Article • Rapidly meeting a surging demand

The science behind 3-D printed nasal swabs

Medical device approved 3-D printers are producing clinically safe and effective nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 testing.

Report: Cynthia E. Keen

Images courtesy of USF 3-D Clinical Applications Laboratory

A nasal swab may seem rudimentary, but is essential for testing COVID-19. Diagnostic test kits and components – nasal swabs, collection vials, and chemical reagents – have been in short supply worldwide, especially in March. Ironically, nasopharyngeal swabs are predominantly manufactured in northern Italy and China, two countries first impacted by coronavirus. Concerned by diminishing supplies and near impossibility to restock, the dean of the University South Florida (USF) Morsani College of Medicine, wondered if the radiology department’s 3-D Clinical Application Division could produce swabs.

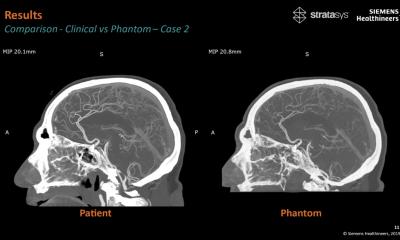

3-D Clinical Applications director and imaging scientist Summer Decker PhD, with Jonathan Ford PhD, biomedical engineer and fellow medical printing expert model, create virtual analyses for simulations of injury mechanics and blood flow, for example, as well as 3-D prints of anatomical models of organs and regions of the body. In two decades of research they produced trailblazing work and numerous publications. Worldwide, their lab, located at USF Health and Tampa General Hospital, is one in about two dozen renowned for this expertise.

Immediately investigating the idea, they started to develop nasopharyngeal swab prototypes that would use materials cleared by the USA’s FDA as patient-safe. They received one representative standard-of-care nasopharyngeal swab to examine before creating a new design for a 3-D printer. ‘On the surface, creating a nasopharyngeal swab doesn’t seem that complicated a design,’ Decker observed. ‘But it’s more complicated than it looks. We knew we couldn’t replicate components of the traditional swab, such as the flocking on the tip which collects the sample. We needed a device that could be printed as one unit, collect a sufficient mucosal and epithelial sample for viral testing, and be safe and comfortable during the collection process. Additionally, the material could not interfere with the actual testing machines.’

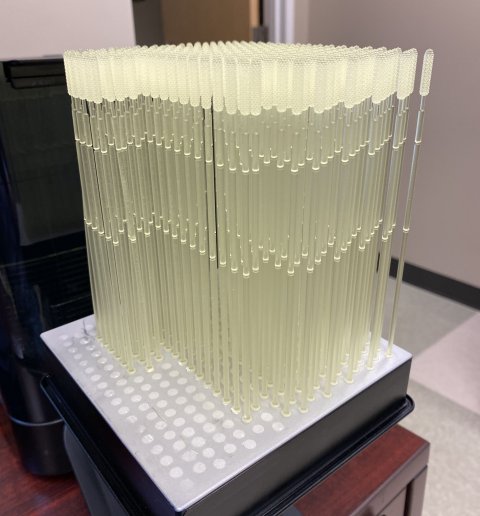

Decker and Ford sought ideas and advice from colleagues. They also invited 3-D medical printing expert Todd Goldstein PhD, director of Northwell Health and 3-D Design and Innovation Center, in Manhasset, NY. The final design team included the 3-D medical printing experts, infectious disease physicians, otolaryngologists, a virologist, and a pulmonary radiologist who suggested rounded ‘nubs’ on the tip of the swab to maximise surface area to collect a sample. Ultimately, 12 designs were investigated and prototypes printed. The prototypes were given to the design team physicians for feedback and consensus. Hospital residents and the design team tested the prototypes on themselves to identify the most comfortable designs. The final design was a standard-length swab with a tip that has a smooth cap on the top to protect the tissue as it goes through the nasal passage. Nubs or ridges in a staggered pattern around the sides collect the sample as it goes into the nose.

An expert virologist performed robust bench lab testing to verify that the swab design would grab enough sample and met viral load detection requirements. The length of time the swab could hold a sample was measured. The swab also underwent rigorous compatibility testing for the collection media and the virus testing machines. The team contacted Formlabs, a digital fabrication company and licensed medical device manufacturer based in Somerville, MA, which manufactures professional 3-D printers. The company worked with USF to optimise the design and production of the prototype swabs.

‘Swab sticks have an intentionally weak point 7-8 cm from the tip, which allows the stick to be broken to the correct length so that the vial can be capped before transportation to a laboratory for testing,’ explained Stephan Hollaender, Formlabs’ managing director EMEA. ‘The most difficult part of designing these swabs to be 3-D printed was ensuring the material was strong enough to be used in a patient’s nose without fear of it breaking, and weak enough that it can be easily snapped and put in a vail.’ USF and Northwell rapidly conducted a 120-person trial comparing the performance of the 3-D-printed swab with a traditional one. The 3-D printed swab performed as hoped, but to make sure, the clinical trial expanded to include 35 hospitals nationwide.

Goldstein’s team is conducting the 3-D printing work for all of Northwell Health, which is a 23-hospital healthcare provider in New York state, the epicentre of the crisis in the USA. ‘We have eight Formlabs’ 3-D printers with the capacity to print about 4,000 swabs a day. By the end of May, the lab had printed over 90,000 swabs which were distributed among Northwell Health hospitals and outpatient facilities,’ Goldstein said. ‘In our efforts to bring nasopharyngeal swabs into production in record time, we helped supply the Northwell Health system with a critical diagnostic tool needed to combat this disease. In a time of crisis, it is ingenuity and innovation that helped keep everyone motivated to help our community as best we can.’ Formlabs is manufacturing the nasophangeal swabs in its 200 3-D printer manufacturing facility in Ohio, and has the capacity to produce up to 100,000 swabs a day when printing capabilities are fully ramped up. ‘We are pricing the swabs to cover their production cost and the investment we made to ramp up production,’ Hollaender explained. ‘We do not intend to produce these swabs long term.’

The USF 3-D Imaging Lab holds a provision patent for the swab with Northwell Health. USF made a decision to share the files with any hospital that has a Formlabs printer through April 2021, Decker explained. Her lab is printing 324 swabs a time per printer using Formlabs surgical guide resin, a process taking between 15 to 30 hours depending on printer model used. After the swabs are printed, they are cured, individually wrapped, and autoclaved, and ultimately delivered to USF and Tampa General Hospital’s infectious disease labs for coronavirus testing. More than 3,000 Formlabs 3-D printer customers worldwide have signed up to print COVID-19 response parts. ‘Formlabs and its partners have produced more than a million swabs so far, and thousands of other medical components and PPE supplies,’ said Hollaender.

Healthcare groups wanting to legally produce swabs may contact Dr Decker: 3dclinicalapplications@usf.edu.

19.08.2020