Systematic infection control in a Maltese hospital

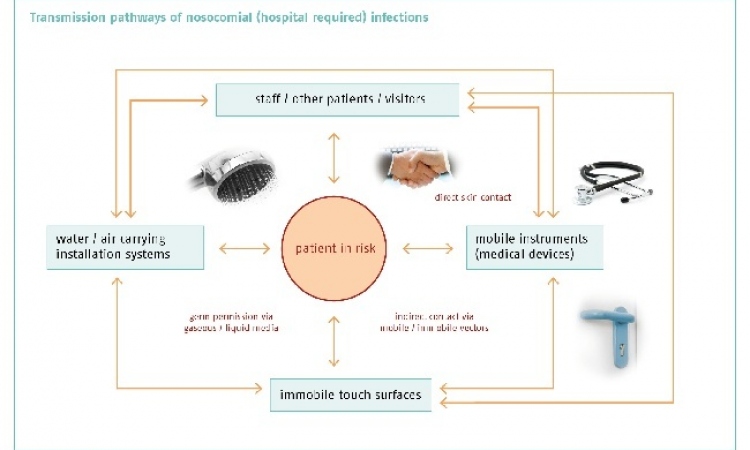

Microbes have been around longer than humans and yet we had to wait till the 19th century for Pasteur and Lister to elucidate their equally beneficial and destructive properties and ways to control their activity and spread. In a hospital, four types of infection transmission can occur: patient to patient, staff to patient, environment to patient and patient to staff in order of incidence. In an interview with Moira Mizzi, Dr Michael Borg, head of the Infection Control Unit at Mater Dei Hospital in Malta, described the ideal infection prevention set-up in a standard hospital. ‘An infection control unit should have an executive arm made up of one infection control nurse per 150- 300 hospital beds; one doctor per 700-1,000 beds and an administrative arm, which is a multi-stakeholder consultative part, namely the Infection Control Committee,’ Dr Borg explains. ‘The latter takes care of setting up policies and getting consensus. At Mater Dei we have four nurses in an 800- bed hospital and an Infection Control Committee, chaired by myself, which makes us quite up to scratch.’ Prevention at Mater Dei Hospital follows a PDSA, i.e. a Plan, Do, Study, Action cycle. ‘Planning involves setting up the policies,’ Dr Borg explains. ‘This is then acted upon by relevant staff training and the provision of consumables and equipment necessary to “do” the “plan”. Regular surveillance is then carried out to ensure that the outcomes of both are satisfactory and the data acquired is used to check out the policies and alter them accordingly.’

This cycle of prevention aims at containing both individual infections acquired during a hospital stay and outbreaks, which can be more problematic as they can cause more morbidity and mortality if uncontrolled. ‘Infections can be acquired either exogenous, that is those occurring outside the body and endogenous infections where bacterial flora could be transmitted from wounds, or the gut, or through the blood stream,’ explains, adding that there are three main ways to prevent the transmission of infection. ‘The best way to avoid contamination is by eliminating the organism at source – that is, ensuring that patients are not exposed in any way. This we do by using sterile techniques for all interventions, major and minor and strictly advocating regular hand washing and disinfection. If infection does occur then hand hygiene measures are stepped up and, if necessary, the patient is isolated.’ He also points to a third way of preventing infection: increasing the host resistance by using antibiotic prophylaxis. ‘It’s still a standard procedure here to give a single intravenous shot of antibiotic post-op, because it has consistently shown to be a very cost-effective way of reducing the onset and subsequently the transmission of infections in the surgical arena.’ Despite its comparatively small size, Mater Dei is still proud of its cohesive infection control system, set up by transposing standards of knowledge and practices from leading expert bodies and institutions, such as the European Centre of Disease Control and adapting these to our local needs. The data from continuous surveillance systems is the living proof of its efficacy. As Louis Pasteur said: ‘In the field of observation, chance favours only the prepared mind.’

11.07.2012