Surgery 4.0

Robots will not see off human specialists

Big Data, automation, and artificial intelligence – no doubt, all these developments will have an impact on surgery. During our interview, Professor Hubertus Feußner, Head of the interdisciplinary research group ‘Minimally invasive interdisciplinary therapy intervention’ at the Technical University Munich, Germany, and Professor Christoph Thümmler, Professor for eHealth at Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh, Scotland, spoke of the role of Big Data and cloud computing in surgery, and intelligent devices that will fundamentally change surgery. They also explain why, despite technological progress, robots will not make the human surgeon obsolete.

Interview: Sascha Keutel

Asked what role big data will paly in the operating room (OR), Professor Hubertus Feußner said that, at this point, ‘Big Data simply means we will have to deal with data volumes that do not grow in a linear manner, but will reach entirely new dimensions.

‘We are increasingly faced with the fact that we need more and more – and above all reliable – data in ever shorter time frames. Case in point: teleconsultation. The external expert assesses the site via a video camera and offers advice and maybe also physically intervenes and can thus significantly influence the procedure. In such a scenario, there must not be the slightest delay in data transmission, as the surgeon needs the required data instantaneously, and reliably.

‘The next data processing level is telesurgery – a still controversial idea. It’s not new; 15 years ago Professor Jacques Marescaux performed the so-called Lindbergh operation. However, due to prohibitive costs and unreliability telesurgery has not yet conquered surgical routine; but this might change with reliable and affordable 5G solutions and it might indeed enhance surgery in certain cases.

Thümmler: ‘Let’s not forget Industry 4.0, which is making inroads in healthcare. The degree of personalisation that Industry 4.0 will bring will not only enhance surgery but also my own discipline – internal medicine. With regard to catheter exams this means that we don’t have to use previously acquired images, but that specific algorithms allow us to analyse images immediately on site.

‘With algorithms that detect more detail than the human eye, we can compare real-time images with previously acquired images. That’s a quantum leap. However, enormous data volumes will have to be processed which requires next generation network technology, such as 5G.’

Is that where the cloud comes in?

Thümmler: There is no such thing as “the” cloud but many different kinds of clouds. Public clouds, such as those we know from Amazon or Google; private clouds that we install at home, or hybrid clouds that are a mixture of both. We have to clearly differentiate here.

For healthcare, the public cloud is utterly unsuitable because the privacy of the patients and the hospital staff as well as the hospital’s business secrets cannot be sufficiently protected. On the other hand, the idea that we feed all data in one huge platform that can be accessed by everybody is unfeasible, as is the idea that we exchange data without the patient’s explicit consent. Software-to-data is a strategy that is worthwhile considering. It means that algorithms and software elements process data on site.’

In the OR the surgeon receives many radiology and lab data. Are data also sent from the OR straight to the cloud?

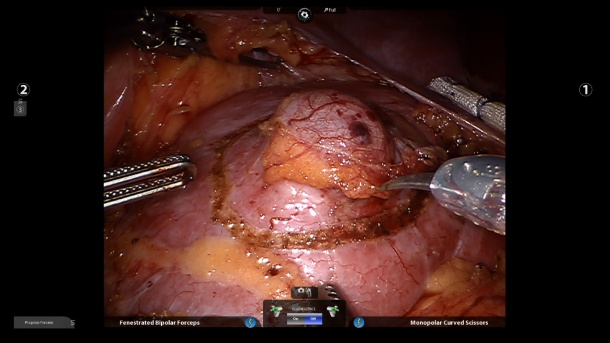

Feußner: ‘Basically, only for teaching purposes or to obtain an outside opinion. The majority of the data volumes are created during intra-surgery tissue differentiation. In cancer surgery, particularly, it’s very difficult to determine whether all malignant cells were removed and the remaining tissue is healthy. Thus, today, we tend to remove more tissue than necessary. To be able to follow the principle “as much as necessary and as little as possible” we have to be able to differentiate tissue during surgery. Currently, the only way we can do this is via an intra-operative frozen section. Our vision is to have sufficient information on hand to be able to answer questions on tissue malignancy during the intervention.’

How could this vision become reality?

Feußner: ‘One option might be a probe that we insert into the tissue and which sends us information. Another option might be automatic differentiation with a scope. We envision a machine, an intelligent device that tells us with what kind of cells we are dealing.

‘This is a tall order for any knowledge-based system and conventional technology cannot yet fulfil it.’

Thümmler: ‘When you want to examine tissue locally and compare it to entries in an existing data base with similar tissue structures, or certain patterns, this is where Big Data comes on stage: We need existing data for comparative purposes, we want to use algorithms to fuse historical data with new data in real-time.’

Feußner: Here data mining, the extraction of knowledge, plays a crucial role. In the future I want to make evidence-based decisions by accessing thousands of similar cases which point in a certain direction and which tell me what I have to expect. To make a decision based on past experience, learned knowledge, that would be a fantastic step forward.

Are we therefore moving towards computer-based and cognitive surgery?

Feußner: ‘Exactly. Cognitive surgery is the combination of experience and learned knowledge, actively supported by intelligent systems or cooperative devices.’

Thümmler: ‘We are talking about cyberphysical systems that link the real and virtual world and communicate with each other in real-time. In the virtual world, we are dealing with algorithms and databases, in the real world we are dealing with the surgeon in the OR. If we can construct systems that activate knowledge in real-time, we are coming pretty close to surgery 4.0.’

We have Big Data and the cloud; very soon we may have learning software and algorithms. Do we still need a surgeon if we can programme a robot with the necessary knowledge – and a robot that could learn from our experience?

Thümmler: ‘Current surgical robots are more or less the surgeon’s extended arm, who still has to treat the patient one to one. That’s an important aspect in the current debate. At the end of the day the surgeon is not superfluous. Indeed, sometimes it is more tiresome to work with the Da Vinci robot.’

Feußner: ‘The term robotics is difficult as it conjures up images of metal and plastic. We should rather call it support or assistance systems or, to use robotics terminology, mechatronic assistance systems. Their role is not to passively perform commands, as with the current master-slave systems, but to work autonomously or semi-autonomously to a certain degree. The system should be able to do the surgical drudgery – tasks that are tiresome, boring or time-consuming, such as tying a surgical knot. With the current systems I basically have to tie my fingers into a knot first in order to tie the suture into a knot. It takes forever. If I could ask a future system to tie a knot, that would be a major help. These things are conceivable. Such skills can be learned with the help of deep learning procedures in robotics.

‘Having said this, the “driving” surgical robot – the robot that acts autonomously, will not be developed in the immediate future, at least not for another 20 to 25 years. After all, surgery is a biological process that is often performed under highly dynamic and unpredictable circumstances and will continue to need human intervention for many years to come.’

PROFILES:

A graduate from Philipps University, Marburg, Germany, Professor Hubertus Feußner MD has pioneered minimally invasive surgery, with the focus on visceral medicine. In 1999 he founded the interdisciplinary research group ‘Minimally invasive interdisciplinary therapy Intervention’ (MITI Institute), which he heads today. He has also published ground-breaking work on medical technology, as well as laparoscopic and scar-less operations.

Professor Christoph Thümmler MD is a specialist in general and internal medicine and professor of eHealth at Edinburgh Napier University. In the 1990s he was already specialising in electronic healthcare systems and, for a number of years, has been expert at a European level for the internet of things and healthcare information and communication technology.

14.11.2016