Radiologists need specific knowledge to assess children and adolescents

Comprehensive additional training is necessary in Germany, to specialise in paediatric radiology, and only seven among the country’s 35 university hospitals provide paediatric radiology professorships. Thus, there are only about 80 specialists in this field and very few work in private practice

Aiming to revalue paediatric radiology, the Ruhr Radiology Congress (RRC) is for the first time dedicating separate events to this subject. Professor Gundula Staatz, who heads the Paediatric Radiology Department at the Clinic and Polyclinic for Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, at the University Clinic Mainz, was among those responsible for the selection of topics. ‘We will provide information on questions that all radiologists may encounter in their practice and which they must able to answer even if there is no paediatric radiologist at hand.’

Within the forthcoming Ruhr Radiology Congress programme related to paediatric radiology are three, somewhat sensitive, diagnostic topics: Bone and thoracic diagnostics and child abuse. The sessions intend to highlight current knowledge and familiarise participants with the underlying diseases.

In bone diagnostics, for example, Prof. Gundula Staatz explains the need to know the musculoskeletal system and growth stages of children and adolescents and be able to classify them. ‘Radiologists need to assess which changes during childhood and adolescence are normal and at what stage you are looking at something pathological. That’s not always easy, because bones can look quite patchy due to haematopoietic marrow.’ Frequently there are also benign changes to the bones, such as non-ossifying fibroma. ‘These normally heal by adulthood and should not be considered as malignant bone tumours.’ Images from infants and young children need a highly trained eye. ‘When it comes to joint diagnostics, it is important that the radiologist knows where the centres of ossification are in children and adolescents, and how the joint cartilage develops.’

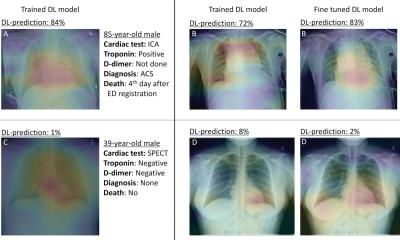

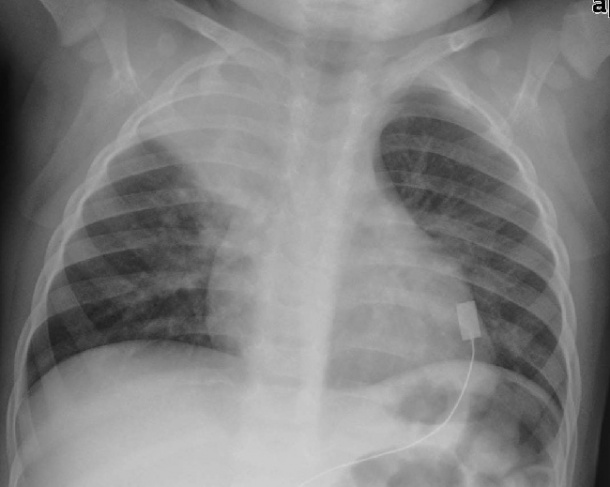

Thoracic diagnostics

The focus of the RRC sessions is on thoracic diagnosis of infants and young children. Questions frequently facing radiologists, she says, include, ‘How do I distinguish between bronchitis and bronchopneumonia? What do I need to look out for in children who show pneumonic changes, i.e. pneumonia, and how do I recognise complications?’ Again, such examinations are all about recognising the specific features of childhood and deciding if and when further examinations with other imaging modalities are needed.

Other thoracic diagnostics subjects will include lung malformations, infectious diseases, tumours in childhood and the diagnosis of foreign body aspiration.

Child abuse

This is one of the most difficult areas in which paediatric radiologists contribute their expertise: ‘Professor Mentzel, from Jena, will introduce a current national study on this subject. It is about the important of second opinions in cases where there is a suspicion of child abuse,’ Prof. Staatz explains.

In recent years, the rate of reported abuse has increased drastically. According to statistics of the Federal Criminal Police Office, she points out, in 1993 there were 800 cases among children under age six years; in 2008 there were almost 2,000. Experts also suspect a high number of unreported cases. Therefore, radiologists -- particularly paediatric radiologists -- need to know the specific indications of child abuse.

Among these, Prof. Staatz points to fractures of different ages, the presence of certain types of bone fragments or also injuries to several ribs, which can be interpreted as potential evidence in the same way as skull fractures above the brim line. ‘Children can suffer injuries below the brim line if they fall whilst playing, but everything above the brim line points towards the presence of an external force.’

Shaken baby syndrome

Here is another important subject: The shaking of a baby leads to potentially life-threatening injuries, such as subdural bleeding and parenchymal brain injuries. Prof. Staatz: ‘In these cases the objective is to determine how old the haematoma are and whether the description of what is supposed to have happened is plausible. In cases of very strong suspicion, other imaging procedures, such as MRI, should be used in addition to cranial ultrasound.’

The procedure in a case of child abuse is generally multidisciplinary, she points out. Mostly it is paediatricians who initially become suspicious and request further radiological examinations. ‘As radiologists we then have to make our contribution to the decision as to whether or not the image fits with the description of how an accident is supposed to have occurred.’ If the suspicion is substantiated, forensic medicine usually becomes involved. ‘Examinations can also be legally requested via the child welfare office if the parents don’t give their permission. In these cases the children are also admitted to hospital by way of protection.’

26.10.2011