Article • Cardiology

Pulmonary valve placement via a child’s liver

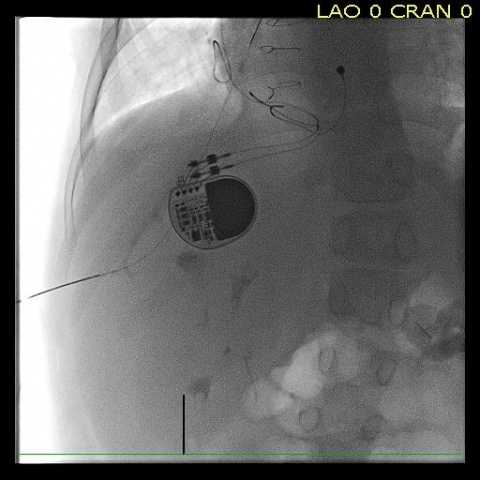

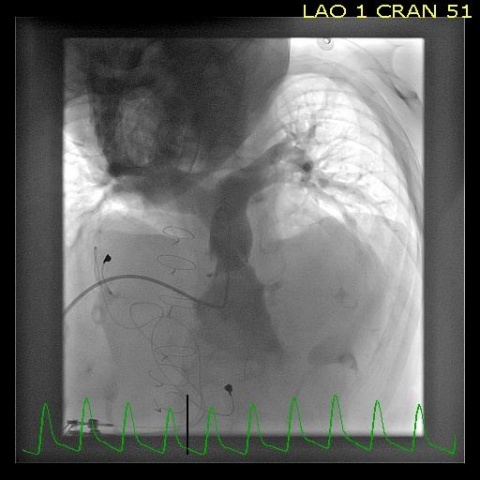

A Spanish team has, for the first time, successfully placed a pulmonary valve using catheterisation through the hepatic vein in a paediatric patient. Specialists believe this type of intervention could become an interesting alternative when traditional access points are not available.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

In what will probably pave the way for further similar interventions, a team at Virgen del Rocío Hospital in Seville has just successfully placed a valve inside the pulmonary artery of a child with congenital heart disease, by entering a catheter in the hepatic vein.

Only the second procedure to be performed

This is the first time this type of intervention has been carried out in a paediatric patient in the world and the first time it has been performed in a patient in Europe. Before that, only one adult patient had undergone this procedure in the USA. Dr José Félix Coserria Sanchéz, a paediatrician who specialises in cardiology and haemodynamics at Virgen del Rocío Hospital, coordinated the intervention. He explained the challenges his team had to face for this type of catheterisation, which is traditionally performed from the femoral or jugular artery. ‘It’s very rare to use liver access for this kind of intervention,’ he explained during our European Hospital interview. Doctors chose to place the valve through the hepatic vein because the eight-year-old patient, whose implant was failing and needed urgent replacement, had already received multiple surgeries to treat a complex heart disease he had been suffering since birth, called Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF).

The haemodynamics team unit benefits from two years’ experience

Opening the patient again with traditional surgery simply presented too many risks, Coserria explained. ‘The child had problems in his trachea and oesophagus. Traditional access points were thrombosed, so they were not viable.’ Catheterisation has been widely used since 2001 to replace cardiac valves when surgery proved inefficient. The haemodynamics unit at Virgen del Rocío Children Hospital has been using this technique for the past two years and performs three to five interventions a year to replace valves through the pulmonary artery. Liver access is sometimes used in catheterisation for congenital heart disease, but in these interventions physicians usually insert a small catheter through the liver and up to the heart. However, this time, due to the large valve size, doctors had to by-pass the organ so as not to damage it. ‘We could have torn the liver or caused important bleeding had we touched the organ,’ Coserria explained.

This is unique in that a child with a congential heart condition is involved

To ensure a successful outcome, Coserria performed the intervention with another haemodynamist, Dr Zunuzegui from Gregorio Marañon Hospital in Madrid, and vascular radiologist, Dr Álvaro Iglesias from Vigen del Rocío, who provided image guidance with fluoroscopy at the time of placing the catheter inside the hepatic vein. Iglesias has performed many liver catheterisations in his career. He also stressed the uniqueness of the procedure in the context of a paediatric patient with congenital heart disease.

‘Catheters we traditionally use in liver access interventions are in the 8 Fr. range. This time we had to use a 22 Fr. diameter, so about 6 mm and a half, which is very big for a patient this young,’ he told European Hospital. Once they placed the tube in the hepatic vein, doctors reached the heart very quickly. The whole intervention lasted less than two hours, about an hour less than when accessing through the neck or groin. ‘We have significantly reduced the duration of the procedure and it was much easier to place the valve inside the pulmonary artery than when using traditional access,’ Coserria said, adding that the patient had fully recovered and significantly improved his quality of life.

Entry via the liver could be used to place a new large valve

These benefits could help establish the liver as an alternative access in pulmonary catheterisation when no other access is available or damaged, or in small patients who need a large cardiac valve, the paediatrician believes. ‘We could,’ he pointed out, ‘use the liver when we need to place a new valve, especially in the case of a large implant that may not fit through the jugular or femoral artery. ‘The liver can definitely be an interesting option in this case,’ Coserria confirmed.

Profiles:

Dr Álvaro Iglesias López has worked as a vascular and interventional radiologist at Virgen del Rocío Hospital since 2004. He performs diagnostic and therapeutic studies in peripheral vascular, hepatic and renal pathology, and procedures involving the placement of central and peripheral venous accesses. He also serves as a general radiologist and carries out CT, MR and ultrasound examinations.

José Félix Coserria Sánchez MD is a paediatrician who specialises in cardiology and haemodynamics. In 2014 he became coordinator of paediatric cardiology at the Virgen del Rocío Children’s Hospital in Seville, Spain. His experience, in all aspects of paediatrics and paediatric cardiology, includes acute admissions and interventional catheterisation, PICU, intra-operative cardiovascular imaging and transoesophageal echocardiography.

30.08.2017