Image source: Shutterstock/DeReGe

News • Promising material

Organ transplantation: polymer coating reduces rejection rate

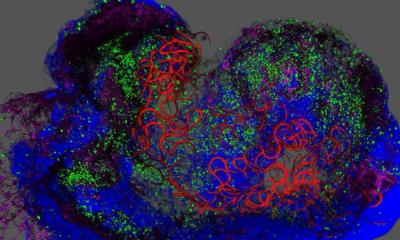

Researchers have found a way to reduce organ rejection following a transplant by using a special polymer to coat blood vessels on the organ to be transplanted.

The polymer, developed by Prof. Dr. Jayachandran Kizhakkedathu and his team at the Centre for Blood Research and Life Sciences Institute at the University of British Columbia (UBC), substantially diminished rejection of transplants in mice when tested by collaborators at Simon Fraser University (SFU) and Northwestern University. “We’re hopeful that this breakthrough will one day improve quality of life for transplant patients and improve the lifespan of transplanted organs,” said Dr. Kizhakkedathu. The findings were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

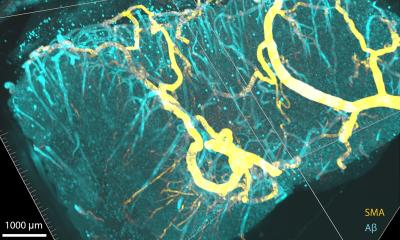

The discovery has the potential to eliminate the need for drugs—typically with serious side effects—on which transplant recipients rely to prevent their immune systems from attacking a new organ as a foreign object. Dr. Kizhakkedathu explained how that problem arises: “Blood vessels in our organs are protected with a coating of special types of sugars that suppress the immune system’s reaction, but in the process of procuring organs for transplantation, these sugars are damaged and no longer able to transmit their message.”

Dr. Kizhakkedathu’s team synthesized a polymer to mimic these sugars and developed a chemical process for applying it to the blood vessels. He worked with UBC chemistry professor Dr. Stephen Withers and the study’s co-lead authors, PhD candidate Daniel Luo and recent chemistry PhD Dr. Erika Siren.

Dr. Siren’s thinking on cell-surface engineering had been inspired by a visit to a BC Transplant facility. “I remember seeing an organ sitting in a solution and thinking, ‘Here’s a perfect window to engineer something right,'” Dr. Siren recalled. “There aren’t a lot of situations where you’ve got this beautiful four-hour window where the organ is outside the body, and you can directly engineer it for therapeutic benefit.”

The work of Simon Fraser University’s Dr. Jonathan Choy and Winnie Enns confirmed that a mouse artery, coated in this way and then transplanted, would exhibit strong, long-term resistance to inflammation and rejection. Dr. Caigan Du of UBC and Dr. Jenny Zhang of Northwestern University then got similar results from a kidney transplant between mice. Dr. Megan Levings of UBC and the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute firmed up the findings using new-generation immune cells. “We were amazed by the ability of this new technology to prevent rejection in our studies,” said Dr. Choy, professor of molecular biology and biochemistry at SFU. “To be honest, the level of protection was unexpected.”

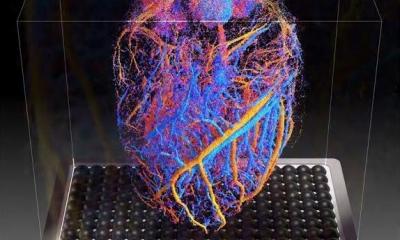

The procedure has been applied only to blood vessels and kidneys in mice so far. Clinical trials in humans could still be several years away. Still, the researchers are optimistic it could work equally well on lungs, hearts and other organs, which would be great news for prospective recipients of donated organs.

Source: University of British Columbia

10.08.2021