Foetal surgery

Scanning and cutting on a miniature scale

Almost 25 years ago Michael Harrison of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) operated on the bladder of an unborn child. Almost eight years later, surgery was carried out on the diaphragm of an unborn child. His approach was controversial: a paediatric surgeon opened the abdomen and uterus of the pregnant woman, lifted out the foetus, performed the surgery and returned the foetus to the womb. The disillusioning result: Almost all these `open fetal surgery´ cases were born prematurely and most died.

Harrison faced not only criticism from experts and laymen, but also respect for his courage and innovation. ‘Late one night, it must have been before my internship, I sat in my room in the hall of residence in Essen Margarethenhöhe and flicked my way through the TV channels when I came across a report on Michael Harrison and fetal surgery,’ recollected Thomas Kohl, today Head of the renowned German Centre for Fetal Surgery & Minimally Invasive Surgery (DZFT) at the University Hospital Bonn. ‘I’ve never been able to get it out of my mind.’

Dr Kohl’s approach has little in common with that open surgery. With a small group of colleagues he has paved the way for minimally-invasive fetoscopic fetal surgery. These new interventions, he says, ‘have fewer complications than open fetal surgery and most importantly, put less pressure on pregnant mothers and their unborn babies.’ Today a whole range of diseases, e.g. twin transfusion syndrome, diaphragmatic hernia, spina bifida and some cardiac problems can be treated in this way, as well as urethral rerouting.

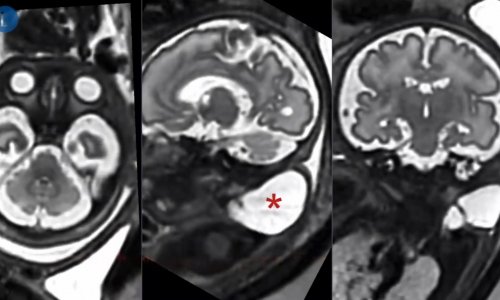

Treating those with spina bifida hold his particular interest. Spina bifida, in which part of the spinal cord is exposed to the amniotic fluid and therefore damaged, can be detected at very early stage pregnancy, using ultrasound and marker protein determination (alpha-1-fetoprotein-concentration). Risk of paralysis increases according to the level of the affected parts of the spinal cord not protected by the vertebral body. Moreover, the cerebellum and the brain stem are displaced.

‘Although children rarely die from spina bifida, diagnosis can be fatal because most couples decide to terminate the pregnancy,’ Dr Kohl pointed out. One reason is that parents are still being given the wrong kind of advice. ‘Contrary to popular perception spina bifida, even if it is not treated with fetal surgery, actually rarely leads to severe mental disabilities. As the opening in many children is quite low, paralysis is less pronounced and despite the characteristic clubfoot they can often walk well enough.’ By surgically closing the back, American fetal surgeons as well as Dr Kohl hope to reduce the extent of palsy and improve the concomitant malformations in the brain so that an affected baby is less disadvantaged through problems developing after its birth.

Thomas Kohl developed and practiced his technique on sheep, operating on about 200 unborn lambs before he dared operate on a human. He also worked under renowned fetal researchers in San Francisco, among them the pioneer Harrison, to perfect his technique. Today he is considered one of the world’s leading fetal surgeons.

‘Around 70% of all babies who undergo fetal surgery survive these interventions along with treatment once they are born,’ he said, ‘and most can expect a normal quality of life.’

The foetal surgery centre in Bonn has operated on more than 200 unborn babies or treated them with new, non-invasive procedures; without these interventions, most of them would have died or would have had to live with severe disabilities.

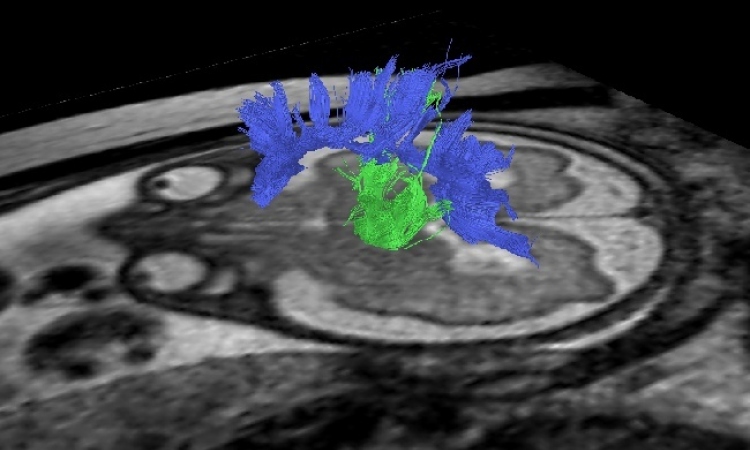

The progress of fetal surgery was significantly dependent on the development of sensitive imaging procedures and the necessary surgical instruments. Ultrasound has proved itself the most important tool. ‘Siemens offers a machine that even allows us to capture images of the oesophagus of an unborn baby with the help of a small ultrasound catheter. This is particularly suitable for monitoring surgery with certain heart problems,’ explained Dr Kohl. The tube containing the ultrasound transducer and the surgical instruments measures only five millimetres. The diameter of the hollow needle he and his colleagues use to treat a fetal diaphragmatic hernias measures just under one millimeter, i.e. less than the diameter of the ink cartridge of a biro. If left untreated, a fetal diaphragmatic hernia can lead to the internal organs shifting into the thorax and can prevent the lungs from developing properly.

Three further quantum leaps in medicine helped the further development of this still relatively new specialty: The change from large, open surgical interventions to minimally invasive procedures from the beginning to mid-1990s and, very topical, the ‘newly developed anaesthetic procedures developed at the DZFT, which allow us to anaesthetize unborn babies safely and effectively without putting too much of a strain on the mother’s cardiovascular system, and finally the ability to close up holes in the amniotic sac,’ explained Dr Kohl.

A hole in the amniotic sac is a problem well known from examinations of the amniotic fluid: It can lead to amniorrhexis and premature births. The longer and more complicated the extent of the intervention, the higher the risk. The main problems feared by the surgeons are births occurring particularly before the 30th week of pregnancy. ‘Up to two years ago this was a really big problem,’ he pointed out, but now around 80% of the babies treated are born after the 30th week, and 50% are actually born after the 34th week of pregnancy.

To avoid very early premature births Dr Kohl tends to treat problems that will only become life-threatening after birth, e.g. underdevelopment of the lungs in the unborn with diaphragmatic hernias, ideally only from the 34th week of pregnancy. Up till then he prefers not to disturb the baby’s development as far as he can. Even at this late stage in pregnancy he achieves sufficient catching up in the development of the lungs in most of his patients treated in this way.

However, there are some fetuses that doctors try to save at the earliest possible stage in pregnancy. The most common cases treated at the Centre are twin pregnancies. With ‘twin-to-twin’ transfusion syndrome the placenta vessels fuse together, causing a life-threatening exchange of blood between the twins. Using a laser, Dr Kohl and colleagues close the vessels, in this way saving most of the babies.

Dr Kohl has now developed a procedure for certain cardiac conditions that does not involve surgery. ‘Ultrasound scans can sometimes show that the left side of the heart is very small and the main artery is very underdeveloped,’ he explained. In over two thirds of cases the baby needs cardiac surgery after birth, to widen the aortic arch. ‘My new approach is to give the mother oxygen in the last weeks of pregnancy. When this reaches the baby the lung vessels open through reflex. This leads to more blood flowing to the left side of the heart, which can then grow further.’ For some babies this completely eliminates the need for surgery after birth; for others doctors are at least able to improve the conditions for this kind of surgery. Dr Kohl has now dealt with 14 of these cases, and has five more already on his waiting list.

How does he find time to develop such new procedures? ‘The good thing about my special subject is that I have comparatively few patients,’ the surgeon explained, ‘therefore I have more time to refine my approaches.’ by Edda Grabar

01.09.2008