Article • Optical imaging

Faster than light

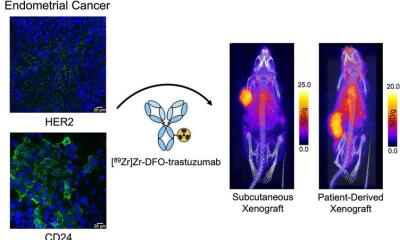

PET scanners are not the only way to image radiotracers. Recent work developed around a phenomenon called Cerenkov luminescence aims to bring a new modality out of preclinical development and into clinical practice.

Report: John Brosky

First noted by Marie Curie, it was Soviet physicists who first described the strange blue light that occurred when charged particles travelled through water. Among the Russian group was Pavel Alekseyevich Cerenkov, who shared a Nobel Prize in 1958 for this work. Long applied in nuclear physics, the Cerenkov effect is now being developed for use in nuclear medicine and biomedical imaging. At the ECR, on Saturday, Jan Grimm MD PhD presents the lecture ‘Cerenkov: Faster Than The Speed Of Light’, offering a review of this new method that promises new ways to image radiotracers and describing advances in both technological developments and clinical studies.

‘Optical imaging with radiotracers is one of the very few new and novel modalities described in recent years,’ said Grimm, who is an Assistant Professor at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Cornell University, New York. He is a Laboratory Head and also Assistant Attending Radiologist in the Radiology and Nuclear Medicine group at Memorial hospital. ‘By combining optical light and radioactivity, we are merging the two fields of optical imaging and nuclear medicine, which creates a whole range of new opportunities with possibly huge advantages for patient care. This is totally new, and can be brought relatively quickly into the clinic because the tracers are all available. We just have to figure out the right clinical setting.’

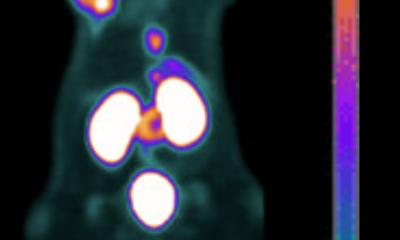

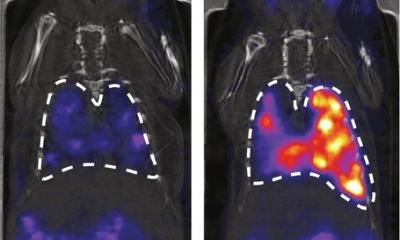

In conventional optical imaging a light is projected onto the area of study to excite an injected fluorochrome. The more external light, the stronger the obtained signal – but also the scatter and reflectance of the external excitation light, degrading the sought after signal. With Cerenkov luminescence imaging the light emanates from the radiotracer within the body. It is an ultra low signal that requires total darkness and very sensitive cameras to be detected.

‘We calculate this light is one billion times weaker than ambient light in an operating room, Grimm explained. ‘To image Cerenkov light means shielding it from this billiontimes stronger light, otherwise it would be like trying to see a candle held up against the sun. ‘We have shown that we can do this even in the clinical setting. This provides us with two types of information coming from one source – the radioactive agent. We, and other groups, are now working to create specific agents that make use of the Cerenkov light and some very unique features that allow us to do some very neat tricks’.

One advantage is better quantification of the light, he said. ‘There are all sorts of light propagation models for radiotracers, but with Cerenkov light we can absolutely measure the radioactivity and then calculate how much light is being generated. We can determine the difference between the light actually generated and the light arriving at the detector, which allows us to calculate an absorption factor for light. Or, as we demonstrated, we can use the light and modulate it to create radiotracer-based sensors, switching Cerenkov on or off with smart tracers to provide additional information one cannot get with just radioactivity alone.’

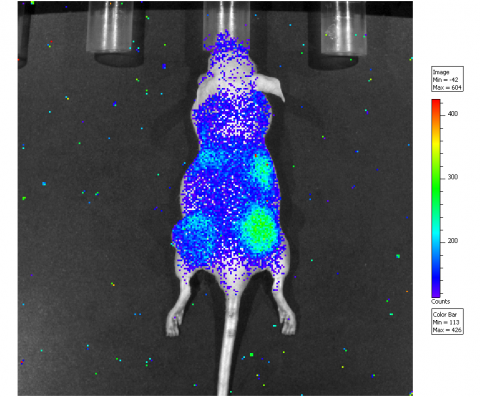

Another advantage of Cerenkov luminescence imaging is the cost of the camera, which is 25% of the cost of a PET scanner. Additionally, in pre-clinical animal studies, where usually one mouse can be imaged at a time with PET, Grimm pointed out, ‘we can image five mice at the same time and it takes about five minutes.’ The ability to capture Cerenkov luminescence remains the great challenge. Going inside the patient during endoscopic procedures shows promise because the human body serves as a natural shield for the faint blue light.

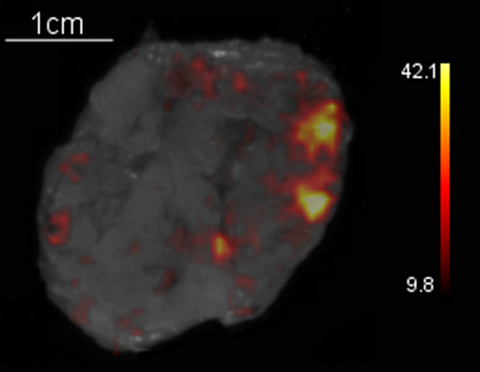

Yet, this presents a new challenge because the aperture for endoscopic cameras is small for the long and narrow instruments, exactly the opposite of the ideal setting for imaging Cerenkov luminescence emanating from a radiotracer. In addition to an on-going clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to explore Cerenkov light in patients, 30 patients are currently being enrolled at the Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust in the United Kingdom for a pilot study to evaluate Cerenkov luminescence imaging using an analyser developed by Lightpoint Medical Limited for the ex-vivo measurement of surgical margin status in breast cancer surgical specimens and the metastatic status of excised lymph nodes.

Another 30 patients are being enrolled at University College Hospital London for a prospective, single-centre feasibility study testing the feasibility of 18F-choline Cerenkov luminescence imaging to measure margin status in radical prostatectomy specimens. Research at Memorial Sloan Kettering, supported by two the United States National Institute of Health and in collaboration with Lightpoint, aims to bring Cerenkov luminescence imaging over the next five years from testing in animals to patients, ‘…and then,’ Dr Grimm predicts, ‘all the way up to an open surgery procedure.’

07.04.2015