Endogenous bacteria

Is chlorhexidine still the best decolonisation method? For many decades decolonisation – be it selective intestinal, oral or skin decolonisation – has been the accepted procedure to prevent infections by endogenous bacteria.

Report: Brigitte Dinkloh

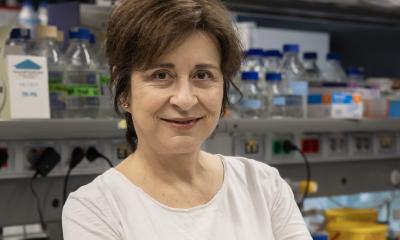

At the12th Congress on Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Professor Petra Gastmeier, Director of the Institute for Hygiene and Environment and of the National Reference Centre for the Surveillance of Nosocomial Infections at Charité Berlin, presented new research on oral and skin decolonisation of bacteria with antiseptics. The title of her talk indicates the results of her study: ‘Reduction of endogenous bacteria: an innovative approach to prevention?’

Oral decolonisation

The problem is as old as artificial respiration: With intubated patients bacteria preferably colonise the cuffs from where they migrate to the lower airways and cause pneumonia. ‘Chlorhexidine is the best researched substance to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in intubated patients,’ Professor Gastmeier explained at the symposium in Cologne.

In the study by Sonia Labeau chlorhexidine received top marks: the scientist could show that the oral antiseptic significantly reduces ventilator-associated pneumonia. However, in his recent review, Boston-based Michael Klompas draws a more complex picture. He concluded that, as far as pneumonia risk is concerned, only cardiac surgery patients benefit from chlorhexidine. For all other patient groups an increase in mortality has been recorded. ‘With regard to oral decolonisation the evidence of the benefits of chlorhexidine is not quite as obvious as with regard to selective intestinal decontamination.

‘One possible explanation of the higher mortality rate is the aspiration of chlorhexidine, which may cause changes to the lung. In view of the fact that, day by day, thousands of patients on ICUs receive oral care with chlorhexidine, further research is urgently needed,’ the Charité professor emphasised, ‘particularly since alternative substances, such as povidone iodine have not yet proven to be particularly well suited.’ The endpoint of future studies, Gastmeier suggests, should be mortality rather than pneumonia risk.

Skin decolonisation

The skin flora is very different from the oral flora and varies from patient to patient and from body region to body region. Accordingly, decolonisation measures can yield widely differing results. ‘No doubt, the skin and its flora play a role in the development of hospital-acquired infections. Already in 2001, Christoph von Eiff was able to show that 82.2 percent of staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections are induced by nasal bacteria rather than by exogenous bacteria,’ Gastmeier pointed out.

Standard decolonisation procedures use mupirocin for the nose and chlorhexidine for the skin. The latter antiseptic is available either as a water solution or as pre-packed impregnated washcloths.

Cohort studies looking at the efficacy of bathing with chlorhexidine showed a significant effect: the bloodstream infection rate decreased by 36 percent with cloths yielding slightly better results than chlorhexidine solutions.

Daily bathing with chlorohexidine

Randomised controlled studies on bathing confirm the positive effects. Climo et al. report that, in their trial encompassing 7,000 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients, the rate of bloodstream infections was 28 percent lower in the patient group who had been washed with chlorhexidine compared to the group who had not received this type of care. Moreover, according to this study daily bathing with chlorhexidine-impregnated washcloths significantly reduces the risks of acquisition of multi-drug resistant organisms (MDROs).

A further study published in the US shows chlorhexidine-impregnated washcloths in paediatrics to reduce sepsis by 36 percent.

Susan Huang conducted the largest and best-known pragmatic cluster-randomised trial. More than 70,000 patients in 43 ICUs were decolonised for five days with chlorhexidine cloths and mupirocin. Endpoints were the MRSA clinical isolate and bloodstream infections. ‘The group undergoing universal decolonisation with chlorhexidine and mupirocin without prior screening showed the best results. Even if universal decolonisation will not reduce bloodstream infections, the reduction of MRSA and VRE-isolation days is a major success,’ Gastmeier underlined. However, she pointed out, the question of long-term efficacy when all ICU patients are universally decolonised remains to be answered.

Conclusion

All four recent studies confirmed significant effects of decolonisation on the bloodstream infection rate and on the reduction of resistant pathogens. Even if chlorhexidine works better with gram-positive bacteria than with gram-negative ones, gram-negative ICU patients should undergo skin decolonisation.

Care staff usually accept chlorhexidine bathing since it does not create an additional burden.

The side effects of the antiseptic are negligible, the Robert Koch Institute, however, reports that in Germany MRSA resistance to mupirocin has increased by seven percent over the past years and even the number of chlorhexidine resistances has been growing.

In Germany, polihexanide and octenidine are available as alternatives, albeit neither of these two substances has been thoroughly tested in clinical studies.

So far no resistances were reported for the cheaper of the two antiseptics, octenidine, and it seems to work better with gram-negative bacteria than chlorhexidine. ‘In short: while the evidence on chlorhexidine to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia is questionable, the evidence on decolonisation to reduce bloodstream infections and the transmission of multi-resistant pathogens is convincing.

‘Most likely it is more effective to treat all patients at risk rather than only those with s. aureus and VRE.

‘Alternative substances have to be urgently tested in clinical studies,’ Prof. Gastmeier concluded, ‘for us to be able to slow down the development of resistances.’

Profile:

Professor Petra Gastmeier MD studied medicine in Halle/Salle and Berlin and has worked as a specialist in Infection Prevention and Control and Environmental Medicine since 1988. Following her habilitation on Infection Prevention and Control at the Free University of Berlin in 1999, a year later she was awarded a C3 professorship for Infection Prevention and Control in the Hospital at Hannover Medical School.

Since 2008 she has directed the Institute for Infection Prevention and Control and Environmental Medicine at Charité University Hospital in Berlin, which acts as a National Reference Centre for the Surveillance of Nosocomial Infections.

10.11.2014