Drug smugglers in the gantry

Security checks – the necessary evil for air and land travellers. While luggage scans and body pat-downs are ubiquitous, drug smugglers have increasingly used their own bodies as a vessel to conceal and transport their goods.

However, the police send suspected ‘body packers’ post haste to a radiologist for an X-ray. Locating the illegal substances with the hit rate of a sniff dog, however, is not an easy feat.

‘Up to fifty percent of the drug bags are not detected by X-ray,’ says Michael Scherr MD, junior physician at the Institute for Clinical Radiology at Ludwig Maximilian University Munich. ‘X-ray is a conventional projection procedure and often visualises the swallowed drugs only vaguely. Moreover, most radiologists are

not experts in body pack detection. Therefore, we see quite a high rate of false findings. Drugs often have a low density, very similar to soft tissue or stools. In addition, drug traffickers today know exactly how to configure the packs so the X-rays will not detect them.

Thus, in our institution, we’re now using CT.’ Creating a CT topogram is often sufficient to be able to ascertain whether drug packs are present or not. If the answer is yes, an actual CT scan is performed. A normal dose CT achieves a hit rate of close to one hundred percent, he says. Often enough a low dose protocol – e.g. as used to detect kidney stones – will do. ‘It’s important to search the entire gastro-intestinal tract from the diaphragm to the sphincter,’ the radiologist emphasises. ‘We try to distinguish between drug packs and stools by looking at unusual structures in the body, for example strange shapes or coverings.’

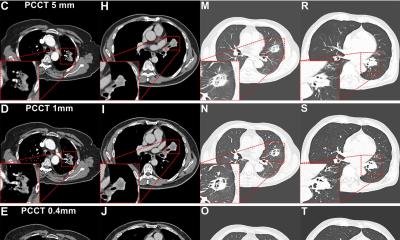

According to Dr Scherr even very low doses yield excellent detection results. Currently the Munich team can reduce the radiation dose for a CT with several hundred individual slices to that of a conventional single plane X-ray. However, dose is not the only factor that influences body pack detection. Success strongly depends on the image settings used, the ‘windowing’. ‘The radiologist should use at least the same values as he would normally choose for a lung scan.

This will detect packs much better. The so-called soft-tissue windowing used for abdominal scans makes detection much more difficult if not impossible,’ Dr Scherr adds. Despite the drug traffickers’ cunning in packaging and sealing of their wares, bags do rupture from time to time inside the body and the substances cause intoxication.

Then, suddenly the body packer is a patient. ‘These different definitions are important from a legal point of view’, Dr Scherr explains. ‘Since a patient’s medical care is subject to medical confidentiality, the physician is not obliged to involve the police.’ While a ruptured 10g pack of cocaine is usually lethal because there is no antidote, heroin intoxication can be treated. Thus, in an emergency, the physician needs to know which drug was carried.

Since early 2009, Dr Scherr has used pig models and in vitro tests to find out how drugs in the body can best be imaged and distinguished. He applies state-of-the-art dual energy technology, which allows him to characterise the drugs and the filler due to their chemical structures. These studies, which are internationally unique, could soon help radiologists worldwide to improve diagnostic methods and hit rates when imaging body packers.

21.02.2012