Article • Coronavirus chronology

COVID-19 in the U.S.: Government inaction gave virus a head start

The sense of fear is palpable in the images and videos of hospital intensive care units (ICUs) and emergency departments that are broadcast on television and posted on social media. Fear and heartbreak can be heard in the voices of physicians and nurses who describe what they are experiencing.

Report: Cynthia Keen

Image source: We Are Covert, SARS-CoV-2 illustration (05), marked as public domain

It’s not as if healthcare professionals hadn’t warned United States residents and government officials. They’d been talking about the potential coronavirus threat since the epidemic first started in China. It’s just that a lot of people, including the federal and many state governments, weren’t listening.

Image source: The White House from Washington, DC, White House Press Briefing (49690431596), marked as public domain, details at Wikimedia Commons

In January 2020, public health specialists and epidemiologists at hospitals throughout the U.S. begin sounding the alarm that the coronavirus might already be prevalent and lurking. How would anyone know without testing? They requested COVID-19 testing kits in huge quantity immediately.

The U.S. federal government had a different perspective. On January 21, the day after the first coronavirus case was announced in the United States, a reporter asked President Donald Trump in a televised press conference if he was worried about a pandemic. The President replied," No. Not at all. And we have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine."

President Trump continued to publicly downplay the threat of the coronavirus for weeks. On February 26th, he stated in a press conference that “When you have 15 cases, and the 15 within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero, that’s a pretty good job we’ve done.” This wasn't quite correct: 60 cases had been reported that morning by national and local news media.

And on March 5th, as the number of cases continued to increase, President Trump stated in a national TV interview that people infected with the novel coronavirus may get better "by sitting around and even going to work". Many people took his advice. They did go to work and "sat around" in public spaces. Nobody knew how many people might be infected with the coronavirus because on March 5th, fewer than 1,300 tests had been performed. That was because test kits that worked weren't available to do so.

Hospitals braced for the epidemic they knew was invisibly happening. The U.S. healthcare model is not prepared to treat surge disease. In fact, in 2018, the Trump Administration dismantled the National Security Council's directorate for global health, security and bio-defense, which had been specifically established by the Obama Administration to deal with a potential global Ebola virus or similar epidemic.

Hospitals and healthcare professionals were on their own.

The coronavirus testing kit fiasco

Image source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control, CDC 2019-nCoV Laboratory Test Kit, marked as public domain, details at Wikimedia Commons

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began to ship coronavirus testing kits to states on February 5th, in quantities for about 800, but a portion had faulty negative controls caused by contaminated reagents. There did not seem to be any prioritization to send the kits where they were most needed, in predominantly large metropolitan areas. The CDC distributed kits more or less equally throughout the United States. Some hospitals began to develop test kits on their own, but this initiative was hampered by the need to obtain federal government agency approval.

On March 8th, with 106 confirmed cases, New York State’s Governor Andrew M. Cuomo criticized the CDC for not authorizing the use of private laboratories. The private Northwell Health Labs had developed an accurate testing kit. “The CDC has not authorized the use of this lab, which is just ludicrous,” Cuomo said. “CDC, wake up, let the states test, let private labs test, let’s increase as quickly as possible our testing capacity so we can identify the positive people.” That night, the CDC issued approvals under an emergency use authorization.

Image source: Metropolitan Transportation Authority of the State of New York, Andrew Cuomo 2016 crop, CC BY 2.0

Gov. Cuomo and Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington State both warned that without adequate test kits, there was no way to determine the spread and extent of infection. Gov. Inslee was particularly vocal on February 29th, when the first person to die from coronavirus in the United States had no known contact with anyone who potentially could have contracted the virus. There was an ominous outbreak as well in a Seattle-area care facility for the elderly. Other state leaders began to echo this sentiment: that the handful of cases being reported represented a “canary in a coal mine” scenario.

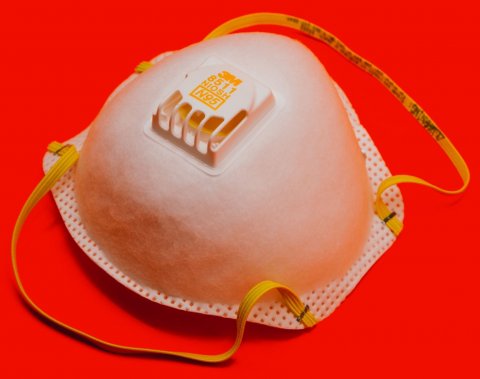

Protection for healthcare workers fiasco

Hospitals throughout the country began to announce in February that there would be a ventilator shortage if the coronavirus became an epidemic, and that emergency supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) -- masks, gloves, and gowns -- would be inadequate to safely treat an onslaught of patients.

Image source: Unsplash/visuals

After blaming his predecessor, President Barack Obama, for the shortage of PPEs in the federal government national stockpile of 13 million masks, President Trump said in a televised press conference on March 21st, “We started with very few masks and now we’re making tens of millions of masks.” He subsequently clarified this statement by saying that the U.S. Government had issued a contract for 500 million N95 masks, and that they were “now” available to hospitals and other health care centers.

But they weren’t and they still aren’t.

Two days before, Scott Steiner, the chief executive officer of Phoebe Putney Health System in Albany, Georgia, a city of about 75,000 well south of Atlanta, told ABC News that his three hospitals had utilized their six-month supply of PPE in seven days. Volunteers with sewing machines in these communities were making washable masks that could be placed over N95 masks.

The mask-making effort is now a volunteer initiative nationwide, although the CDC warns that the majority of surgical masks being made does not have the protective capability of N95 masks. Clothing manufacturers large and small, have joined this initiative. Others are making protective gowns.

Hospital experiences in Colorado, Illinois, Georgia

Colorado currently ranks 13th, with 43 deaths among 2,000 cases. Centura Health System operates 15 small-to-medium-sized community hospitals throughout the state. One of these, the 231-bed Littleton Adventist acute care Hospital with a Level II trauma center and 24 licensed ICU beds, is located in the suburbs of Denver. Dr. Mark Elliott, the hospital’s medical staff president, spoke with European Hospital about advance preparations that were representative of all Centura hospitals.

“As early as 2002, following the 9/11 attack in New York City, we began holding exercises and otherwise preparing for large-scale infection outbreaks. In January 2020, Centura Health System and our hospital began preparing specifically for the arrival of the coronavirus,” said Dr. Elliott. “This included planning for supplies conservation, the need for additional staff, and making contingency plans for isolating patients. On March 3rd, we activate our Incident Command Center to coordinate future preparation, manage care, and provide updates to staff.”

In addition to the test kits it received from the federal government, Littleton Adventist Hospital also created its own test kits to send to the state’s laboratory. The hospital initially tested any patient suspected of having the virus, but transitioned to testing patients being admitted to the hospital subsequently to save testing kit supplies. The hospital has invested in negative airflow rooms, and is currently able to handle the number of patients admitted with COVID-19. It has 21 ventilators on premise. Centura Health, unlike many other hospital systems in the U.S., anticipates having enough ventilators to meet its hospitals’ needs. Like many U.S. hospitals, it has suspended elective surgeries.

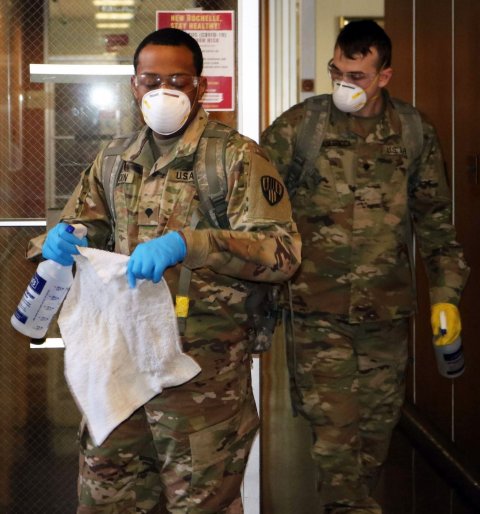

Image source: The National Guard, New York National Guard (49662901907), CC BY 2.0

Chicago and its suburbs are poised to become a coronavirus “hotspot”, within a state that reports 50 deaths and nearly 5,000 cases to date. Like N.Y. Gov. Cuomo, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker holds daily press briefings, and is one of the most vocal governors regarding the need for the federal government to develop an intelligent and coordinated response relevant to the needs of the most impacted cities and regions. Gov. Cuomo was the first to urge mobilization of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to build temporary field offices and for the U.S. military to assist states and hospitals in crisis mode, including allowing admission of patients to government-run military hospitals.

The NorthShore Health System includes four suburban community hospitals and a fifth located in Chicago. In January 2020, each hospital created a cross-functional team of physicians, nurses, and operational and administrative staff to proactively prepare to deal with COVID-19. The team meets daily, reviewing the systems, supplies, staff and communications to inform readiness planning. In addition to expanding COVID-19 isolation units and negative-pressure patient rooms, clinical and medical personnel are optimally mobilized in physician, nursing and general labor pools for optimized flexibility. NorthShore was the first Illinois hospital system to implement its own fully validated in-house testing, a capability it launched in 2010 during the swine flu epidemic. Results of the approximately 600 tests conducted daily arrive within 24 hours. Testing is being reserved for symptomatic, high risk individuals.

WellStar Health System, with 11 hospitals and more than 300 medical office facilities in Georgia, has acted similarly. It is braced for the onslaught that Atlanta is expecting.

Many U.S. hospitals have significantly restricted visitors to non-infected inpatients. New York-Presbyterian and Mt. Sinai Health System, for example, do not allow any visitors for adult patients, and will not allow the partners of pregnant women to be present in delivery and labor rooms. Postponements of chemotherapy and radiation therapy have been reported around the country, as well as suspension of routine diagnostic tests, such as screening mammography. Specialty hospitals, such as the orthopedic Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, have seen an increase in uninfected patients requiring orthopedic-related surgery and treatment.

Most ominously, some hospitals are discussing “do not resuscitate” policies. No hospital has yet formally implemented such a policy for COVID-19 patients. But physicians have anonymously reported on social media that they make life or death choices for the sickest of COVID-19 patients on a daily basis.

New York City hospitals are expected to run out of ventilators and PPE soon. Clinical staff shortages are also expected throughout the state. Gov. Cuomo called for a volunteer work force retired physicians, nurses, and technicians to staff hospitals, and more than 60,000 responded.

30.03.2020