Congenital heart defects

Justus: A very special case

The German Paediatric Heart Centre (DKHZ) is one of the largest of its kind in Europe. Over 25 years the centre has treated big and small patients with congenital heart defects, very now and then being faced with rare, individual cases that present very particular challenges. In any one year, consultant paediatric cardiologist Professor Martin Schneider MD encounters perhaps five such non- textbook cases. Among these was Justus, born with a unique, mixed form of congenital heart defect that resulted in a variety of coronary diseases.

Before his first birthday, Justus had undergone two operations and six cardiac catheterisations. The fact that he is still alive and that his health is actually improving is due to the expertise of paediatric cardiologist Professor Martin Schneider, who has performed minimally invasive interventions since the early ’90s. The professor believes he has benefitted from his initial start in his medical career as a cardiac surgeon – a career path hardly taken nowadays. ‘If you want to carry out surgical interventions as a paediatric cardiologist you have to think like a surgeon,’ he explains. ‘But paediatric cardiologists in Germany tend to have a background in paediatrics and don’t want to be surgeons. Furthermore, training times are usually extended by several years due to the required specialisation, so it is extremely difficult to find junior specialists in this field.’

At birth, Justus was diagnosed mainly with ‘pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum’. The pulmonary valve, normally pumping venous blood from the right ventricle into the pulmonary arteries, was closed. ‘This also means that the right ventricle, which normally pumps deoxygenated blood from the body into the lungs, is underdeveloped as it is not functional,’ Prof Schneider points out. ‘Instead, blood supply is ensured via a hole between both atria (atrial septal defect) and via the ductus arteriosus.’ In foetal blood circulation, when the lung is not yet active, blood flows directly from the pulmonary artery into the aorta via this duct. After birth, the duct closes within a few days. However, in children with a pulmonary atresia, this vessel has to be kept artificially open with drugs or a stent to guarantee blood supply in the opposite direction, i.e. to the pulmonary artery. Additionally, a catheter is normally used to ‘burn’ a hole into the closed pulmonary valve with a high frequency wire and the heart valve ring is permanently widened with a stent so that the right ventricle starts to pump blood into the pulmonary artery in the right way. The ‘burnt out’ valve must be replaced at some stage. In older children, this intervention is now also possible via a catheter.

In the Justus case things were far more complex. Untypically for this heart defect, he had so-called major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs), vessels that run directly from the main artery (aorta) to the lungs and which have a high system pressure. Due to these competing blood vessels his actual pulmonary vessels were underdeveloped because they were exposed to increased pressure from the MAPCAs. ‘These vessels can be closed after opening the pulmonary valve either interventionally via coil embolisation or surgically through unifocalisation,’ Prof Schneider explains. ‘The surgeon diverts the MAPCAs by connecting them with the pulmonary artery. This is a long and difficult operation, mostly with unsatisfactory results, as the vessels of these MAPCAs were exposed to high pressure and are therefore comparable to those of an 80-year-old suffering high blood pressure.’

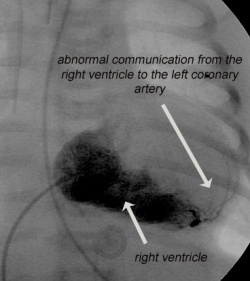

For Justus this intervention to promote the growth of the pulmonary arteries was completely impossible because his pulmonary arterial disease goes hand in hand with coronary anomalies – coronary sinusoids – an undesirable connection between the coronary vessels and the right ventricle which, although small, contains such a high pressure due to the closed pulmonary valve, that parts of the coronary vessels are supplied through the right ventricle, i.e. backwards. Prof Schneider seen the phenomenon in this type of cardiac defect. It was considered beyond treatment. ‘If the pulmonary valve is opened through an intervention this would artificially lower the high pressure in the right ventricle and therefore endanger coronary blood circulation, which could lead to a fatal heart attack,’ he explains. ‘So, neither the cardiologists nor the surgeons could open the pulmonary valve. A connection between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery was also not possible because the pulmonary vessels were too small.’

Was this a hopeless variation of pulmonary atresia? Prof Schneider drew on a hope – although Justus had limited heart function due to the coronary sinusoids, the boy had a comparatively large, fairly functional right ventricle. Using a procedure never performed before, the professor succeeded in closing the connection between the left and right coronary artery and the right ventricle by implanting several closure systems into most of those undesired connections. With the last of the connections, the vessels leading into the right ventricle were very finely spread. ‘I catheterised directly into the right ventricle and looked for the delta of the coronary artery that led into it so that I could close it with a coil. Unfortunately, the coil was too large – and could not be retracted. It was left in a stable position in the right ventricle and removed after a few days during the planned cardiac surgery.

This surgical operation to establish a connection between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery had only become conceivable because the connections of the coronary arteries had now been closed, and because the underdeveloped pulmonary artery had started to develop due to a stent in the duct, inserted during an earlier cardiac catheterisation. Immediately after the surgery the flow between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery was so good that the MAPCAs could be closed with coils and umbrella devices in the cardiac cath lab.

‘The objective of these interventions in the treatment of such complex heart defects is not only to repair something but also to promote the growth of the underdeveloped structures. Only if the structures can be exposed to more blood flow will they develop,’ Prof Schneider points out. The right ventricle now stands a very good chance of normal development – something even he describes as a ‘real miracle’. Exactly what the future will bring for Justus remains to be seen. There are no comparable cases to enable guesswork. A lot depends on whether or not any further complications with the coronary arteries occur. Inserting a stent might be possible when the boy reaches adulthood. ‘The older Justus gets, the better the chances of working with implants,’ explains Prof Schneider, because ‘the materials currently available have been designed for adults. Congenital heart defects therefore differ from the norm in many ways.’

20.12.2011