Clostridium difficile infection

The realisation that the fight against C. difficile needs its own specific hygiene management dawned relatively recently. Up to the new millennium a common perception regarding European hospital infection prevention and control was that this bacterium was under control; it was considered a marginal phenomenon, which is why C. difficile was not the focus of problematic pathogen monitoring.

A crass misjudgment, as the outbreaks in 2005 – 2007, with epidemic and hyper-virulent strains in almost all European hospitals, showed.

Ever since, C. difficile has been very much on the radar, but the fight against the bacterium requires a different type of management than that used against other pathogens.

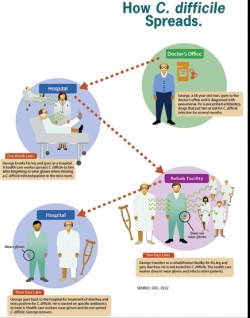

In healthy people, C. difficile is a harmless intestinal bacterium. However, if competing types of normal enterobacteria are impaired by the administration of antibiotics Clostridium difficile can spread unhindered, producing toxins that can lead to life-threatening diarrhoeal diseases.

To survive in the air, C. difficile encapsulates in spores secreted via the gut and are not only resistant against many disinfection agents, particularly against alcohol-based hand disinfectants, but also against almost all antibiotics. They can survive in sinks, bedpans, on floors or in sanitary rooms on the wards and thus infect other patients.

‘The phenomenon of the epidemic was associated with the introduction of new fluoroquinolones (quinolones of the 3rd and 4th generation), which initially were not thought to have a selection risk for the intestine, but against which the strains of Clostridia proved resistant,’ explains Dr Markus Hell, Medical Director of the Division of Medical Microbiology at the Centre for Hospital Infection Prevention and Control in University Hospital, Paracelsus Private Medical University (PMU), Salzburg, Austria.

Subsequently, this led to a shift in awareness in infection prevention and control because these strains were very different from the pathogens known hitherto, also regarding their spore formation and infectiousness. Hygiene, particularly hand disinfection, was strongly scrutinised. Alcohol-based hand disinfectant, which, for the first time, was recommended as the preferred hand hygiene procedure in the CDC-prevention guidelines, is sufficient for everything – with the exception of bacterial spores. The only effective measure against C. difficile, a typical spore former, is mechanical removal, i.e. hand washing with water and soap.

‘The procedure, as described in the guidelines, with the wearing of disposable gloves, alcohol-based hand disinfection to kill the vegetative pathogens and then hand-washing, has proved to be too time-consuming and extensive for patient management in hospital. Therefore, what I recommend is ‘reverse surgical hand-washing’: first you disinfect for the vegetative part of the pathogens, then you wash hands to mechanically remove the spores,’ Dr Hell explains.

In the latest infection control and prevention examinations it has been shown that, apart from transmission via the hands, an important contributor to spores transmission is surfaces.

Surface disinfection v. specific disinfection

In a study first introduced at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in Berlin last April, and due to be published soon in the Journal of Hospital Infection, Dr Hell showed that surface disinfection in defined areas is highly likely to prevent the infection of further patients. ‘Systematic disinfection, which was introduced to reduce the use of aggressive chemicals, in fact does miss its target. By the time you realise that a patient has become infected and the laboratory result is available, several days will usually have passed and the spores will long since have spread and been transmitted to other patients.’

In an open intervention study at the PMU, hyperendemic zones, such as those found in gastroenterology and oncology and surfaces near patients, were preventively disinfected. Hospital-acquired C. difficile infection was clearly reduced, even when new patients were admitted to hospital with diarrhoea and C. difficile. The effect was particularly noticeable amongst older patients who are most prone to the disease.

‘With our concept, we disinfect all patient contact surfaces around the bed, i.e. the bed base, door handles and sanitary fittings with so-called peroxides twice daily. The level of spores in the vicinity of patients was systematically reduced. Transmission does not occur from staff member to staff member but through the patients themselves releasing the spores into the environment and the nurses working with them then becoming reservoirs, and for the next person to absorb these spores,’ Dr Hell concludes, referring to the study results. The rate of infection expected in over 70-year-old patients was reduced by more than 61.5% through the new surface disinfection concept. When a case of C. difficile occurs, disinfection is extended to include floors and all horizontal surfaces.

The study also evaluated disinfection agents. Unlike in the USA, where chlorine is used, Europe only allows so-called peroxides, organic compounds that release oxygen radicals with a sporicidal effect. Usually, the product is supplied as a powder and has to be manually prepared. As there is no guarantee as to the correct mixing ratio, the study also included a first ever evaluation of the only liquid peroxide available on the German market. This suspension has proved to be advantageous because inadequate disinfection due to incorrect preparation can be ruled out.

‘With the enormous cost pressures the hospitals face, which often makes them save on cleaning concepts and staff, this is an important aspect,’ Dr Hell explains. ‘Disinfection is only effective if carried out correctly.’ Therefore it is very important to employ long-term, qualified cleaning staff with whom communication is ensured. ‘Ten, fifteen years ago we were just the experts on disinfection measures and we could rely on everything working correctly. However, this has changed. If we, the infection prevention and control specialists, do not actively intervene with cleaning issues there will be no improvement in infection and prevention control in hospitals!’

Profile:

Dr Markus Hell has been head of Infection and Prevention Control at the University Hospital Salzburg since 2000.

In 2012 he also became Medical Director of the Division of Microbiology.

A specialist in infection and prevention control and microbiology, he studied and wrote his doctorate at the Medical Faculty of the University of Innsbruck and then worked at the Community Hospital Oberndorf, near Salzburg, and the city’s Neurological University Clinic until 1995.

His particular interests are resistance epidemiology, management of nosocomial outbreaks, monitoring of problematic pathogens and management and prevention of nosocomial infections. C. difficile-associated infections (detection, epidemiology, prevention and treatment) have been his key interest and research focus for the past five years.

05.11.2013