Article • Cardiac regeneration potential

Cell combination heals damaged hearts

Researchers have discovered a unique combination of cells grown from stem cells that could prove pivotal in helping a heart regenerate after a patient has suffered a myocardial infarction.

Report: Mark Nicholls

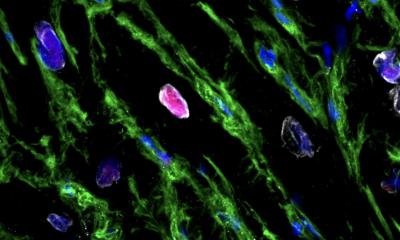

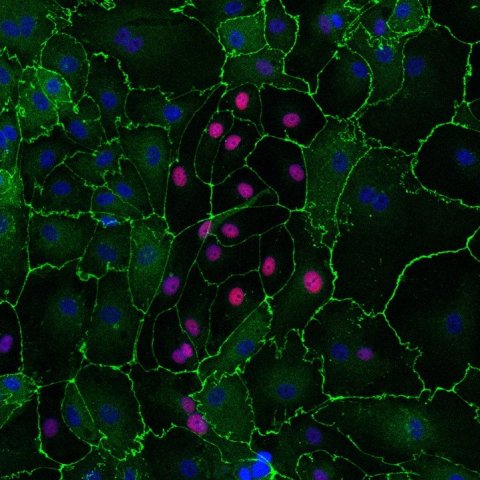

Image: Dr Laure Gambardella

The University of Cambridge research team found that transplanting an area of damaged tissue with a combination of heart muscle cells and supportive cells, similar to those that cover the outside of the heart, might help the organ to recover from damage caused by a heart attack.

In Cambridge, consultant cardiologist Dr Sanjay Sinha and team – collaborating with researchers at the University of Washington, in Seattle – have used supportive epicardial cells developed from human embryonic stem cells to help transplanted heart cells to live longer. To test the combination, they used 3D human heart tissue grown in the lab from human stem cells and found that the supportive epicardial cells helped heart muscle cells to grow and mature and also improve the heart muscle cell’s ability to contract and relax.

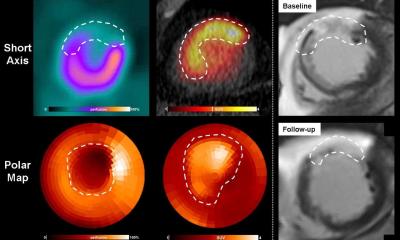

In rat models, with hearts damaged through myocardial infarction, the combination also allowed the transplanted cells to survive and restore lost heart muscle and blood vessel cells. ‘Basically what we have discovered is what we think is the right combination of cell types that will effectively regenerate a damaged heart. Dr Sinha, who is also a consultant cardiologist, said: ‘People who have had a heart attack often do not have much viable muscle left, so the heart does not contract as well. What we would like to do is use stem cells to generate new heart muscle and then actually inject those new heart muscle cells into the heart.’

For the research, the team posed the question of how they could improve the function of cardiomyocytes from a stem cell that did not contract particularly well. Realising that epicardial cells are essential for cardiomyocyte to develop normally, the team mixed heart cells generated from a stem cell with epicardial cells. With the heart muscle cells and epicardial cells generated from embryonic stem cells, and the two derivatives injected to regenerate a damaged rat heart, the results are already proving significant. ‘We found the grafts that regenerate muscle were two-and-a-half times as big in these animal models than if we did not have epicardial cells, so they make a huge difference to the amount of new muscle that is basically regenerating that damaged heart. I think that is a big step,’ Sinha said.

Heart cells do not work best by themselves. They need other cell types to support them

Sanjay Sinha

‘We found that epicardial cells were as good or better than any other cell type that we tried. The heart cells are more mature, they contract better, whole heart function is better and there are more blood vessels inside new heart muscle. Heart cells do not work best by themselves. They need other cell types to support them. We know these epicardial cells are great supporting cells when the heart develops, so we are using that same principle to support the heart cells when we regenerate the heart. The beauty of this approach is that nature has been telling us the answers all along because, in development, this is what nature does, it gets different cell types to work together. We have just taken that principle from development and applied it now to regeneration.’

Image: Dr Laure Gambardella

Sinha hopes his team’s approach will be more successful than that of other centres that have generally focused only on heart muscle cells. ‘We have shown that a combination of cell types works much better than heart muscle on its own,’ he confirme4d, though he acknowledged there is some way to go before using the cells in human patients. From trials in rat, the team plan to validate their findings in a larger system, such as a pig model, with a view to first-in-man trials in five years’ time.

He is confident the current discovery is a major step forward and praised Dr Johannes Bargehr, first author of the study, and the Cambridge team, as well as Professor Chuck Murray in Seattle, USA. ‘We should also acknowledge the patients who have damaged hearts and heart failure,’ Sinha added. ‘I see them in hospital and they are the inspiration for what we do.’

Transplant is the main treatment for heart failure, so finding an alternative is essential. BHF Medical Director Professor Sir Nilesh Samani said: ‘When it comes to mending broken hearts, stem cells haven’t yet really lived up to their early promise. We hope that this latest research represents the turning of the tide in the use of these remarkable cells.’

Profile:

Dr Sanjay Sinha is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Cambridge (funded by the British Heart Foundation) and an Honorary Consultant Cardiologist at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge. His research interests focus on the use of stem cells to understand and treat heart disease.

03.09.2019