Article • Antimicrobial resistance development

AMR and climate change: a worrying dual threat to global health

Climate change and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are forming an alarming alliance: Global warming creates new breeding grounds for resistant bacteria, which challenge human, animal, and environmental health systems globally. A serious and very real threat to public health – but not quite the doomsday scenario some might make it out to be, says Prof Sabiha Essack from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa.

Report: Wolfgang Behrends

Photo: supplied

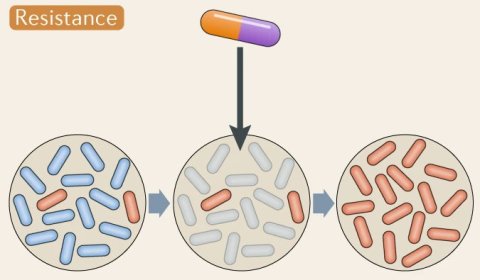

‘Antimicrobial resistance and climate change exacerbate each other,’ Prof Essack says. ‘Studies have shown that rising temperatures together with high population densities lead to higher AMR in bacteria – maps that show increases in temperature correlate with areas where more resistant bacteria are found.’1 Because the transfer of resistance genes is facilitated at higher temperatures,2 the bacteria can acquire and spread AMR genes more easily. ‘If you look at the informal settlements in South Africa, the slums in India, or the Favelas in Brazil – the constellation is always very similar: high population density in a warm climate. This is a combination that promotes antibiotic resistance.’ As global warming progresses, these high-risk areas become more common, creating new breeding grounds for resistant pathogens.

Hunger for meat fuels AMR development

The growing demand for meat protein and other animal products is another major driver of AMR, especially in low and middle-income countries. Animals are raised on a large scale, with regulations on antibiotic use not being very strict.

The practice of prophylactic antibiotic supplementation of feed – which is cheaper than vaccinating the animals – is especially problematic in this regard, Prof Essack points out. ‘Not only does this promote escalation of AMR, but the larger number of animals also leads to increased methane emissions, speeding up the greenhouse effect.’3 Also, without proper preparation of the food produced from these animals, humans run risk of ingesting resistant bacteria themselves.

Biosecurity is a key element to mitigate AMR instead of using preventive antibiotics in food animal production, the expert says: This concept includes the use of vaccines, establishing “all in/all out” systems and thorough disinfection in production sites to prevent resistant pathogens from emerging and spreading from one herd or flock to another. Shifting from intensive to extensive and organic farming models may further reduce the need for antibiotics and the subsequent risk of AMR development. ‘This is more expensive, but it is a vital step to reduce AMR,’ she says.

Emerging from origins hot and cold

Image source: Cavicchioli et al., Nature Reviews Microbiology 2019 (CC-BY 4.0)

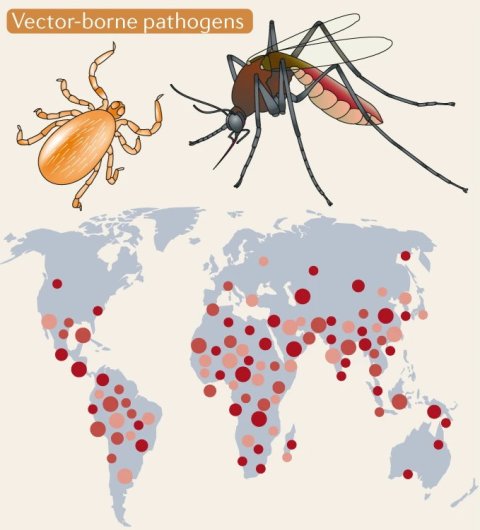

‘Along with the rising temperatures, the ecosystems are changing,’ Prof Essack continues. ‘This leads to floods, droughts, and other natural disasters. Microbes adapt and spread to new areas, as do insects that serve as vectors for new diseases. As a result, more antibiotics are used, increasing selective pressure on pathogens and thus promoting the development of AMR.’

However, global warming not only facilitates the development of new resistance but might even bring back old ones as well: ‘Climate change accelerates glacier melting and thawing of permafrost, which may contain antimicrobial resistance genes.4 Increased oceanic currents further help the spread of these AMR traits from Siberia and the Arctic to other parts of the world.’

For Prof Essack, the re-emergence of ancient resistant strains does not come as a surprise: ’Antimicrobial resistance has existed for millennia. It is our overuse and misuse that has severely tipped the balance and turned resistant pathogens into a significant global threat.’

Increasing health literacy without fearmongering

To counteract the self-propagating effects of AMR and climate change, public awareness is essential, the expert says: ‘Antimicrobial resistance is a very intangible concept, so most people will not make the connection between the deaths from hospital infection and resistant pathogens.’ This awareness is even less pronounced for animal health, leading to a “the cheaper, the better” mentality in meat shopping in some settings where health literacy levels may be low.

Image source: Cavicchioli et al., Nature Reviews Microbiology 2019 (CC-BY 4.0)

The main objective for awareness campaigns is to clarify the consequences of AMR – and to do so in an engaging way: ‘If we allow this development to continue, it will fundamentally change our healthcare standards. Many common surgical procedures such as C-sections or implant surgeries will become impossible to perform, and untreatable infections will lead to premature death.’

Despite this, doomsday scenarios and fearmongering are not necessarily the way to go, Prof Essack believes: ‘We can achieve a lot with just little changes in our behaviour – sparing, prudent use of antibiotics and running diagnostic tests to determine the type of pathogen before administering antibiotics – to ensure that our supply of effective antibiotics do not run out.’

To further loosen our dependency on antibiotics, a number of innovative and promising approaches aim to not only develop new antibiotics, but also antibiotic alternatives, such as bacteriophages.5 ‘Our arsenal of antibiotics is limited, not least because development of new antibiotics is not very profitable,’ the expert points out. To be prepared for the future, financial models should be established to incentivise research and development of new antibiotics, independent from the current return-on-investment model.

Profile:

Professor Sabiha Essack, PhD, is Vice Chair of the WHO Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Antimicrobial Resistance (STAG-AMR) and Advisor for several international initiatives on antimicrobial resistance. She further serves as expert consultant on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) to the WHO. Professor Essack is chairperson of the Global Respiratory Infection Partnership (GRIP), served as Vice Chairperson of the South African Ministerial Advisory Committee on AMR and was a member of the South African Chapter of the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership (GARP) and the South African Antibiotic Stewardship Programme (SAASP). Professor Essack’s current research interests include evidence-informed strategies for the prevention and containment of antibiotic resistance, characterization of the molecular epidemiology of resistance in humans, food animals and their associated environments, as well as health policy and health systems strengthening to optimise the management of infections in the context of antibiotic resistance and stewardship.

References:

1 MacFadden et al., Nature Climate Change 2018: Antibiotic resistance increases with local temperature

2 Brito, Nature Reviews Microbiology 2021: Examining horizontal gene transfer in microbial communities

4 D’Costa et al., Nature 2011: Antibiotic resistance is ancient

28.04.2022