When is our hand not our hand?

When we look at our hands, how do we know they are part of our body? This seems like a strange question because it is something most of us take for granted. Exciting new data from a research group at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden show that the brain uses a combination of sensory signals from our eyes and limbs to achieve a sense of ‘body ownership’.

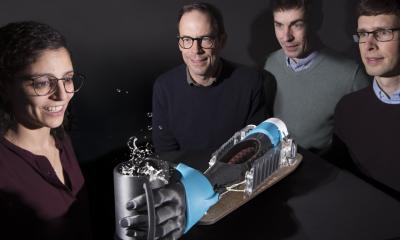

Manipulation of this perception is proving useful making prosthetic limbs feel more like part of the wearers body, and even to give them a rudimentary sense of feeling.

Speaking at the 7th FENS Forum of European Neuroscience today (7 July 2010), Professor Henrik Ehrsson, who heads up the group, said, “We are interested in how the brain creates a boundary between ourselves and the world. We are trying to figure out more of the processes that make the normal mind continue to identify our own body, and using brain imaging techniques to learn more about the underlying mechanisms”.

Recent work from Professor Amir Amedi (working with his students Z. Tal, R. Geva and N. Zeharia) from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel, has shown that our brains store a number of topographic maps, including some relating to the whole body, and others relating to mental imagery of the body or sensory perception of a body part. Still others were multisensory, combining information from different sources (for example, auditory and visual or tactile and visual information). Incoming sensory information that creates a feeling of body ownership helps to maintain these maps, and Professor Amedi’s work suggests that these different brain areas must work together to provide a coherent sense of body ownership.

Professor Amedi explained, “There is a great advantage in discovering all the different sensory, motor and imagery representations of the body their connections, because our very intimate perception of ourselves is embedded in these maps. From a clinical point of view, these maps could assist the study, in a non invasive manner, of plastic changes in perception of body part configuration following, for example, limb amputation”. In the future, Professor Amedi hopes to expand this insight. “we would like to deepen our knowledge about the features of the different maps and to link this basic research work to knowledge and open medical questions about the body (e.g. phantom pain, amputation, stroke)” he said.

Part of these maps includes a template of our bodies, a body-centred reference framework. When sensory information comes in to the brain from a limb, if it fits with this template, and ‘fits’ with other information from the eyes about the position and appearance of the limb, the brain will conclude that it is part of the persons body. “By manipulating the congruency - by changing the timing of the sensory stimulation or how we stimulate, we can explore what are the principles that determine when you will feel ownership of this object and when you will not feel ownership of this object,” said Professor Ehrsson. He also has new data showing that the view of a limb from the first-person perspective is essential for a sense of body-ownership: it isn't possible to ‘own’ another person’s body when looking at it from the third person perspective.

This process that the brain uses to create the boundary between our body and the rest of our environment is a flexible, dynamic process, and these qualities allow it to be manipulated into creating so called ‘perceptual illusions’. An example of this would be persuading a person that a rubber hand is their own, which is very easy, according to Professor Ehrsson. “If you see the rubber hand in front of you stroked on the index finger, and you feel the index finger of your real hand being stroked behind a screen, and the direction of the strokes are in the same direction from a body-centred, hand-centred co-ordinate system, the brain will simply fuse the [congruent] sensory signals and you start to feel the touch on the rubber hand. The brain will decide “’oh, this is my hand’.” he explained.

These perceptual illusions also have a practical application: to help those who wear prosthetic limbs to feel that their prostheses are a ‘real’ part of their bodies, and even give the wearer a perceived sense of feeling.

Professor Ehrsson said “We have started work with surgeons and engineers to develop a new type of prosthesis to be more like real limb, and we don’t do this by trying to directly hook up nerves or electronic devices - there are a lot of attempts to do that - here we are trying to trick the mind - to get the mind to accept the prosthesis as their own.”

Looking forward, Professor Ehrsson and his group have many exciting projects in the pipeline combining brain-machine interface technology and body ownership manipulation to provide enhanced prostheses, and looking at the relationship between phantom limb pain (a common and sometimes severe consequence of limb amputation) and sense of body ownership, in an effort to reduce this problem.

Picture Credit: pixelio/ Peter Kirchhoff

03.08.2010