Article • Pre-, post- and interoperative

Wearable devices in the surgical environment

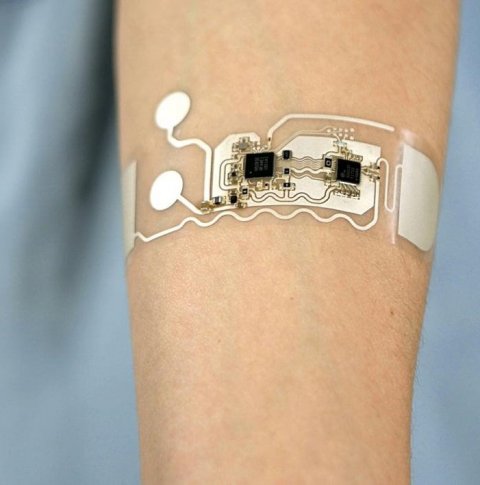

Wearable technology has become an important part of medicine, from tracking vital signs to disease diagnosis. In surgery, wearable technologies can now assist, augment, and provide a means of patient assessment before, during and after surgical procedures.

Report: Sascha Keutel

Pre-operative

Wearable technologies are applied before the patient even reaches the operating room, for example in prehabilitation, i.e. pre-treatment rehabilitation. In a current study, researchers used smartwatches and mobile applications to deliver prehabilitation before major abdominal cancer surgery. Results provided early indicative evidence that such technologies can improve functional capacity prior to surgery.1

In trauma care, first responders can transmit real-time data to the hospital to provide data for the staff to prepare for the patient. This allows the hospital team to plan staff and equipment for the incoming patient. In addition, wearables are used in surgical training to track the physiologic response of learners and educators to better assess and understand stressors in real and simulated surgical environments.

Intraoperative

Wearables can replace physical tasks, e.g.in a sterile environment. For example, surgeons use arm-mounted devices for gesture control of a PACS to review imaging data without breaking sterility.

Surgeons use smart glasses or heads-up displays to receive clinical or biometric data in real-time or superimpose diagnostic imaging, such as a CT scan, onto the operative field at the patient. Neurosurgeons in the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, part of the University of Miami Health System, adopted the Reveal fluorescence-guided system. This headworn device provides better illumination, giving surgeons more precise guidance to differentiate between brain tumors and healthy tissue. The system is essentially a super high-tech headlamp that shines light wherever the surgeon is looking. The system magnifies the surgical area and offers different light options to light up tumor cells.

Checking for fatigue among surgical staff

Wearables and sensors are also used to monitor staff in the operating room to avoid fatigue and resulting errors. They could also be used to analyze data in order to provide assistance, e.g. nurses can be shown the instruments to be used in the next phase of surgery.

Carla Pugh MD PhD, professor of surgery at the Stanford School of Medicine, participated in a multiinstitutional collaboration called the Surgical Metrics Project. The project harvested data from audio and video recordings of surgeons and wearable sensors that measured motion, brain waves and tactile pressure. Instead of parsing every dataset of a surgery, Pugh and her team looked for overarching trends. The motion-tracking sensors fed visual data back to a computer, allowing the researchers to see movement patterns of a surgeon’s hands, including where they paused and where they spent more time.

The aim was to understand how specific motions and decisions correlated with the quality of the surgeon’s work. ‘To me, collecting surgical data is less about evaluating the skill of a surgeon and far more about quantifying what it took to take care of a specific patient,’ Pugh said.2

Patients vulnerable to unoticed deterioration

Wearable sensors are used to measure disease severity and clinical outcomes. They also enhance patient safety. Current standard of care in surgical wards leaves the patients mostly unmonitored during their stay, leaving them vulnerable to unnoticed deterioration. Continuous monitoring of a wide range of parameters can indicate early signs of deterioration, lowering risks of complications and potentially helping patients recover faster.

Postoperative

Scientists at Lawson Health Research Institute found out that a simple device can reduce swelling after a kidney transplant. The geko device is a non-invasive, self-adhering, battery-powered and recyclable muscle pump activator which significantly improves blood flow by stimulating the body’s ‘muscle pumps’. Patients who used the device following kidney transplants experienced shorter hospital stays and reduced surgical site infections by nearly 60 per cent. Researchers at Johns Hopkins Neurosurgical Spine Center are developing wearable devices to be implemented during surgery to allow continuous, postoperative treatment of acute, subacute, and chronic spinal cord injury.

The team’s goal is to build and test three implantable devices and three wireless wearables that work together to monitor perfusion pressure, oxygenation, temperature and other biomarkers, as well as deliver interventions.

The wireless wearables include a blood pressure imaging sensor, a bladder volume imaging and pressure sensor, and an electromyography tracking sensor. These technologies would deliver real-time data to one software application that will help inform treatment decisions. Finally, GE Healthcare and VTT are jointly developing lightweight wireless sensors to ensure patient safety in recovery and freedom after surgery.

Benefits and risks to the OR

Wearable and sensor technology brings both benefits and risks to the OR. Properly used, it has the potential to greatly improve efficiency and accuracy of surgical care. Wearables can assist staff and provide a means for an objective and real-time assessment of the patient. However, staff needs to be trained properly in their use and policies need to be put in place to ensure that the generated data is used appropriately.

References:

1 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00464-021-08365-6

2 https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2019/12/tracking-the-movements--minds-of-surgeons-to-improve-performance.html

16.11.2021