Article • Standards

We expect to see some changes

Strictly speaking, digital pathology has not yet resulted in any groundbreaking changes for clinical diagnostics. The conventional light microscope introduced to pathology around 100 years ago continues to be the most important tool for pathologists.

Report: Marcel Rasch

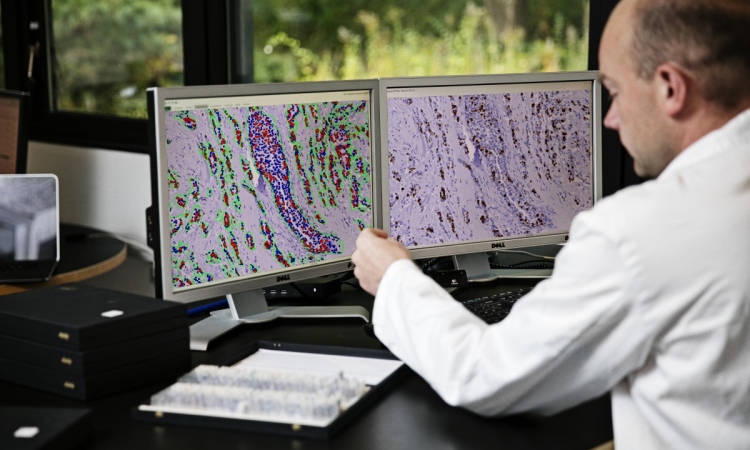

Nevertheless, in the future, according to private lecturer Dr Frederick Klauschen, Head of the Molecular and Systems Pathology Group and Consultant at the Institute for Pathology at the Charité Clinic Berlin, we can expect to see some changes from the introduction of digital technology. ‘Digital pathology is supporting us already in making information from tissue sections more easily quantifiable with the help of computer assisted systems,’ says pathologist Dr Frederick Klauschen. ‘However, when it comes to pattern recognition, and therefore tumour typing and classification into malignant or non-malignant tumours, the pathologist will remain superior to the computer for the foreseeable future.’

Let the computer do the counting

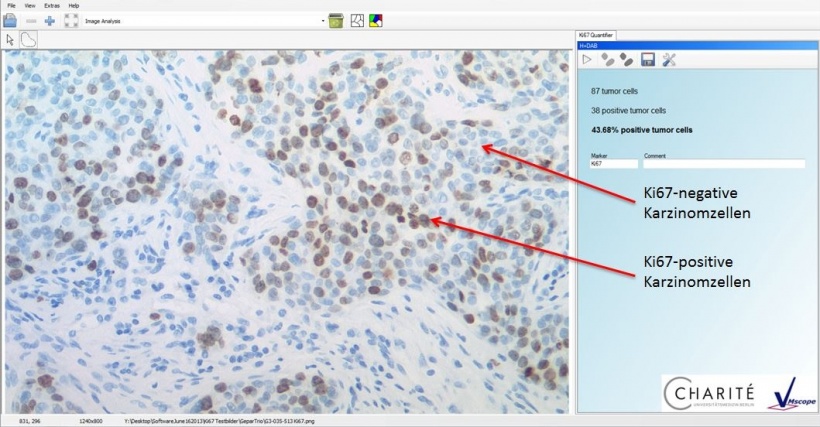

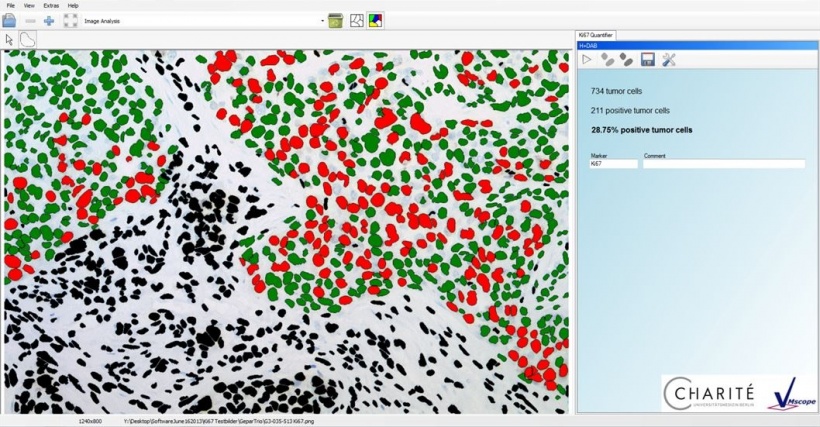

To date, the biggest innovation is a more objective and standardised view and quantification of certain tissue characteristics facilitated by image analysis procedures. ‘One example of this is the measurement of the proliferation index,’ Klauschen says. This can be determined via the immunohistochemical detection of the protein Ki67, which is found in the cell nucleus of proliferating cells. The result normally shows some individual cell nuclei in the normal histological colour (blue) and other cell nuclei where Ki67 is detected in brown or red shades.

Counting the frequency of the brownish colours was once something the pathologist had to do ‘manually’. Now, however, the counting can be done with the help of a computer, using representative image regions. ‘We have developed a specific programme for this purpose, the so-called Ki67 Quantifier. This software supports us with the counting and determination of the proliferation index. It facilitates standardised, automated and precise quantification,’ Klauschen explains.

‘We work very closely with the German Breast Group with regards to breast cancer, for the validation of such procedures.’ Tumour samples that arrive, from all over Germany and other countries, are examined in the Institute for Pathology at the Charité Clinic, which acts as a pathology reference centre. The above-mentioned software is then utilised in the context of these studies and validated based on clinical data.

Digital procedures are currently being developed and tested to examine different types of tissue characteristics and markers. ‘However, many of these procedures are not yet ready for use,’ the pathologist points out, adding: ‘although some Institutes are already using these software solutions it will take some time before all areas of diagnostics will benefit from them.’

Common problem – lack of standards

One big problem with the practical application of image analysis procedures is the lack of standards. Although there is a dialogue and exchange between the various areas of pathology, the analysis of tissue slides from different labs is difficult, the specialist regrets. There are no unified standards regarding histological colourings. ‘Each laboratory produces slightly different depths of colours, so the sections differ from one another. Pathologists are not normally worried by a stronger pink or blue – a computer, however, then may have problems with the classification. The objective is the development of procedures which are independent of colour,’ he emphasises. Although previously not an important topic in pathology, these types of standardisation are works in progress, having gained importance only with the introduction of digitisation.

Klauschen sees a further difficulty in the practical implementation of digitisation in day-to-day pathology. ‘Although we have the technology available, scans of sections are only compiled for special studies, conferences, or for research projects. The actual pathology workflow is not digitised.’ One reason for this is the vast number of tissue sections produced at the Institute every day and the related expenditure of time for the digitisation of each section.

The data volume of the images still represents a big problem as pathological images have much larger file sizes than those in radiology, for instance. ‘We have amounts of data which simply represent big challenges for the IT infrastructure. There is room for development here, particularly regarding the archiving of all this data.’ Klauschen is aware of only two institutes where the workflow is completely digitised – one in the Netherlands, the other in Sweden.

Despite the numerous challenges the pathologist believes that digital pathology means progress, which, in future, will also play an important part in the integration of conventional-morphological and molecular pathology. ‘Fluorescence-in-situ hybridisation visualises genetic changes in the tissue. Digitisation and computer-assisted evaluation can be of enormous benefit here. ‘I also believe that digital pathology will become important for the interpretation of molecular profiles in the tissue context.’

Profile:

Frederick Klauschen MD is a pathologist, physicist, lecturer and consultant as well as Head of the Molecular and Systems Pathology Group in the Institute for Pathology at the Charité University Clinic in Berlin. Up to 2009 he worked at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, USA and he is currently a Junior Fellow at the Einstein Foundation in Berlin.

23.05.2016