Visualising prostate cancer

Advances in prostate cancer imaging spark hopes for better therapies. Meike Lerner asked Professor Hartmut Huland, Medical Director of Martini-Klinik in Hamburg, and pioneer of the nerve-preserving prostatectomy method, currently the gold standard in prostate cancer therapy, about his technique and whether the optimism regarding imaging is justified or misplaced

Prof. Huland: Nerve-preserving prostatectomy was originally developed in the United States. Researchers discovered that the nerves that cause erection run along the surface of the prostate gland and that those nerves are destroyed in traditional prostate surgery. Our work generated important new insights regarding the actual sensitivity of these nerves and we concluded that any surgical intervention should stay clear of these nerve bundles. We were also the first to show exactly where and how many nerves are on each side of the prostate gland – namely fifty. That told us how much tissue had to be spared during surgery in order to preserve erectile function.

Based on this new knowledge, we developed a procedure, which — at Martini-Klinik — has proved very successful regarding the preservation of sexual potency. Because there usually is no comprehensive follow-up, it is not so easy to collect data. Therefore, in 1991, we began to build a data base, which we feed with internationally validated questionnaires that patients fill out before and after surgery.

Surgical success depends to a great extend on the patient’s age and whether the nerves on both sides of the prostate can be spared during the intervention. Normally, this means that, if the patient is fully potent prior to the procedure, and if the nerves on both sides of the prostate can be preserved, 60 percent of the patients will regain erectile function without the aid of medication. A further 30 percent can have intercourse with the aid of potency-supporting medication. If the nerves were spared only on one side of the prostate, only 40 percent of the men can have an erection without medication. Generally speaking, the chances to preserve erectile function are higher for a 50-year-old patient than a 65-year-old patient.

This year, you began a research project on diagnostic imaging of prostate cancer with Professor Dr Ferdinand Frauscher of University Hospital Innsbruck, Austria. Which methods are you studying?

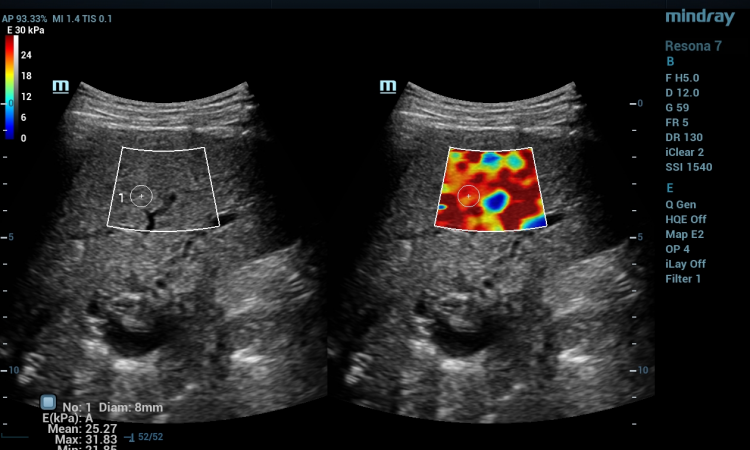

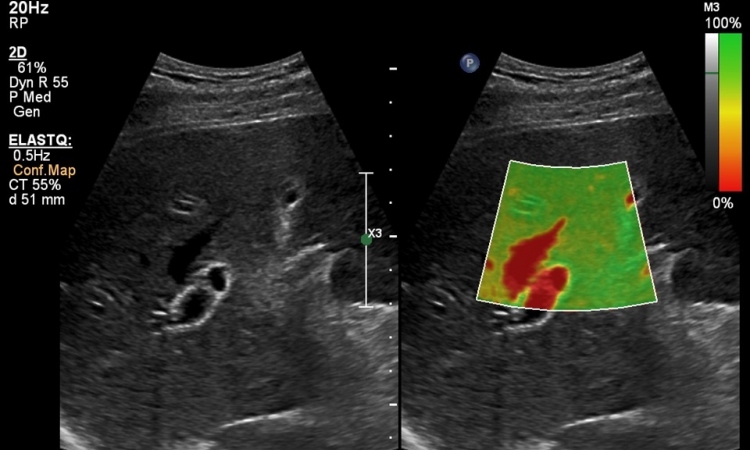

Until recently there was no imaging method for prostate cancer. Professor Frauscher is a pioneer in prostate imaging. In our research we follow a two-pronged approach: First, elastography, a method that has been around for some time, but which did not provide adequate resolution. However, due to recent innovations, the method is now suitable for diagnostic purposes. In the framework of our research project, to test the specificity of the method we are looking at ‘normal’ prostates. We are examining patients who will have to undergo a radical prostatectomy due to a bladder carcinoma. Using elastography, we assess the status of the prostate prior to and after surgery. We compare the actual status with the diagnostic image. Second, we test Doppler ultrasound, a modality also advanced by Professor Frauscher. This ultrasound procedure primarily visualises vessels. Since Doppler sensitivity by itself does not provide sufficient sensitivity, we use a contrast agent. As yet, we have results for neither of these approaches, but we are confident that we will have answers soon.

How do developments in diagnostics impact on therapy?

Currently, we experience problems with identifying patients who are suited for nerve-preserving prostatectomy. The nerves are located very close to the membrane of the prostate capsule. If the tumour has already penetrated the capsule, the nerves are affected. In fact, the tumour uses the nerve sheaths through which the nerves enter the organ, in order to exit the prostate.

Today, there are three methods to determine on each side whether the tumour has penetrated the capsule. First we look at the biopsy results. If the tumour turns out to be aggressive, the tissue-sparing procedure is impossible. In some cases, prior to surgery we additionally perform a biopsy of the nerve region to confirm that there is no, or only little, cancer growth. During surgery, a microscopic examination of the nerve bundle region run will show whether the tumour touches the nerves.

This is very complicated. If we had imaging procedures that could tell us, without a doubt, that on the left side the tumour is inside the capsule but on the right it has already penetrated the capsule, for example, we could plan the intervention far better. The surgeon could determine beforehand where nerves can be preserved and where not. This is what we hope for: that imaging will provide us with diagnostic confidence and complex and time-consuming methods become obsolete.

Second, we certainly hope that imaging will improve early detection of prostate cancer, so that more patients will be able to benefit from the nerve-sparing procedure. The further the cancer has progressed, the smaller the chances for nerve-preserving tumour removal.

In the long term, does this mean that radical prostatectomy will remain the procedure of choice, or do you expect that at some stage you will be able to save the prostate at least partially?

Radical prostatectomy will remain the procedure of choice. It is being hotly debated whether we will reach the point where we can do a partial removal. However, many experts, including myself, consider this discussion dangerous because, in 86 percent of cases, prostate cancer, even in the early stage, is a multi-focal event, unlike kidney cancer, for example, where the carcinoma is limited to a single region. Molecular biological studies show that the entire prostate is always affected. Therefore partial prostate removal is risky. Certainly, we have to think about the idea, particularly if diagnostic imaging provides good results. But it is unlikely that it ever will be more than an idea.

01.03.2008