Simply operate giddiness away?

Only surgery can provide help for some forms of dizziness, writes Karl Eberius MD

A compressed cranial nerve by blood vessels is responsible for numerous diseases. The most well-known example is trigeminal neuralgia, which is agony for many people affected by its sudden shooting pain in the face.

Other examples are glossopharyngeal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm or even superior oblique myokymia in which, likewise, too close contact between a cranial nerve and a vessel is assumed to be the cause.

Medication or the extensively used positional manoeuvre should not be the only treatments considered for effectively helping cases of dizziness. Surgery can also be useful for some forms of dizziness as shown by the case of a 61-year old woman who suffered repeatedly from vertigo. Most recently her problems had become even more severe. She had sudden attacks of vertigo several times a day, which were of strikingly short duration. The unpleasant event lasted from just 30 seconds to a maximum of five minutes, usually accompanied by a whistling sound in the right ear. Another particularity was the fact that the attacks ceased when the patient lay down on her right side, as was reported in the journal HNO [ENT] by Dr Wolfgang Reuter and team from Lippstadt, Germany.

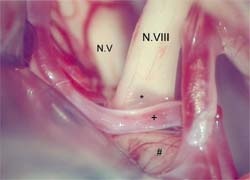

These typical symptoms indicated vestibular paroxysmia (disabling positional vertigo) which is well-known for its extremely short attacks lasting from seconds to minutes and which can be triggered or ended by certain positions of the head. Tinnitus, sounds in the ears, is also characteristic accompanying symptoms for this diagnosis. The cause of disabling positional vertigo is an artery of the cerebellum being compressed by the VIII cranial nerve from, which not only consists of fibres transmitting the sense of balance but also contains the auditory nerve.

Test treatment with carbamazepine clarifies the situation

The diagnosis of disabling positional vertigo was confirmed in the 61-year old woman by treating with carbamazepine, a low dose of which is recommended as first line therapy for vestibular paroxysmia in various guidelines, but which for most other forms of dizziness is useless. However, success was not long-lasting. In just a few weeks, the administration of carbamazepine led to a considerable increase in liver enzyme values, whereupon the treatment had to be discontinued and the gruelling vertigo attacks returned in full force.

To end the suffering it was finally decided to undertake surgery to widen the gap between the compressed cranial nerve and the artery causing the problem. Indeed the agonizing spells of vertigo disappeared completely after the operation, which took some two to three hours and required a hole of around 2.5 cm in diameter in the skull. After the surgery, the woman was able to lead a normal life.

Rate of complications: roughly 5–8%

The decision for such an intervention however should be carefully considered on account of possible complications, emphasized Professor Friedrich Albert, head of the neurosurgery unit of Paracelsus Hospital, Osnabrück, after carrying out the surgery on the vertigo patient. ‘The operation is only recommended if the patient’s everyday life is considerably restricted because of the attacks and the diagnosis of disabling positional vertigo is unequivocal.’ He pointed out that this surgery carries a roughly 5–8% risk of serious complications, e.g. loss of hearing, facial paresis, or vascular damage that could lead to corresponding ischaemia of the brain stem.

The chances of success of such an operation cannot be precisely quantified owing to lack of data, but according to Prof Albert

they are thought to be good. Complete freedom from symptoms, or at least a marked improvement, can be anticipated in about 75–80% of cases, much the same rate as for trigeminal neuralgia – likewise caused by too close contact between a vessel and a cranial nerve.

*Compression through contact with blood vessel, VIIIth n. Vestibulocochlear nerve, +Branch of the the anterior inferior cerebellar a., #Pons (Source: Reuter W., Fetter M., Albert F.K., HNO 2008; 56: 421-424, pic 3, © Springer Medizin Verlag 2007).

01.09.2008