News • “Defanging” dangerous bacteria

Pathoblockers: a future alternative to antibiotics?

In most cases, antibiotics are a reliable form of protection against bacterial infections. They have saved billions of human lives since their introduction.

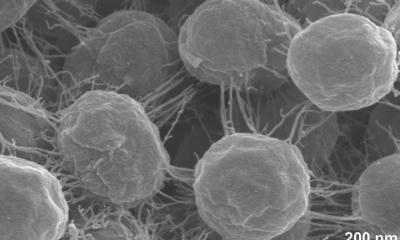

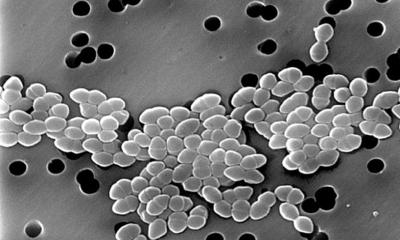

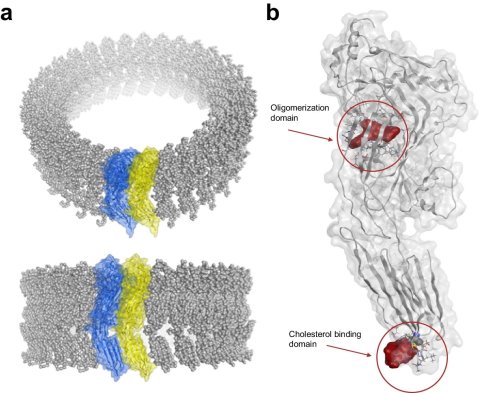

Image source: Azit UBA et al., Nature Communications 2024 (CC BY 4.0)

This protection, however, is threatened by bacteria’s resistance to classical antibiotics and by their aggressive pathogenicity. Currently, one in seven bacterial pneumonia patients in Germany dies while hospitalized – despite the use of antibiotics. This amounts to about 30,000 people per year. The cause of death in these cases is often toxins released by the bacteria, which attack and ultimately destroy the cells of the infected person. Antibiotics do not protect against these bacterial toxins. A study published in Nature Communications now raises hopes for new treatment options.

Researchers at Freie Universität Berlin and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin have succeeded in developing molecules that provide protection against the most common pneumonia-inducing pathogens. They are calling these molecules “pathoblockers.”

Recommended article

Article • Bacterial defense mechanism

Antibiotic resistance: a global threat to healthcare

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is becoming more prevalent around the world, constituting a serious threat to public health. When bacteria acquire resistance against antibiotics, common medical procedures – for example, in surgery – become impossible due to the high infection risk. Keep reading to find out about AMR research, development of new antibiotics and antibiotic alternatives.

The novel substances do not kill the bacteria, but instead switch off the toxins they produce. Normally, these toxins attack the cell membrane of human cells during an infection, piercing small holes into them, thereby killing the cells. “We have identified molecules that inactivate bacterial toxins even at low concentrations, rendering them harmless. By applying these compounds, we were able to show that it should be feasible to completely protect human lung cells,” says Jörg Rademann, professor of pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry at Freie Universität Berlin and director of the research project. In their new paper, Rademann’s group demonstrated that the new pathoblockers modify the bacterial toxins in such a way that they lose their aggressive toxicity. The researchers are continuing to investigate whether such novel pathoblockers might be applicable for clinical use in the future.

Source: Freie Universität Berlin

17.05.2024