MRI helps detect life-threatening pregnancy complication

A study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) revealed that MRI is a highly accurate means of identifying placenta accreta, a potentially life-threatening and increasingly common condition that is the leading cause of death for women just before and after giving birth.

"Due to the increase in cesarean sections and other surgeries that leave scarring on the uterine wall, coupled with women giving birth later in life, the incidence of accreta has increased dramatically over the past 20 years," said lead researcher Reena Malhotra, M.D., a radiologist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) in La Jolla.

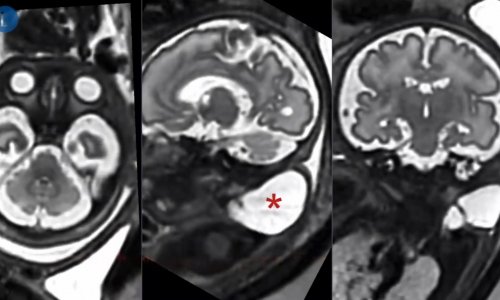

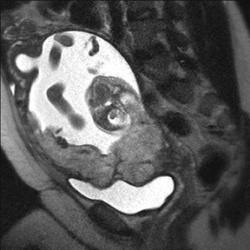

Placenta accreta, in which the placenta surrounding a fetus attaches too deeply to a woman's uterus, is most dangerous when the condition is not detected until the time of delivery. When a placenta that is deeply attached to the uterus is delivered along with a baby, it pulls with it parts of the blood-rich uterine wall, rupturing blood vessels that can lead to severe hemorrhaging in the mother, as well as complications for the baby. Severe cases, particularly when undiagnosed, may lead to massive hemorrhage requiring blood transfusion, hysterectomy or death of the mother.

While routine prenatal ultrasound is often able to identify the presence of placenta accreta, it is not always able to definitively diagnose subtle cases.

To evaluate the accuracy of MRI in diagnosing placenta accreta, 108 patients underwent MRI evaluation at UCSD between 1992 and 2009. The women were referred for MRI based on a suspicious prenatal ultrasound or clinical examination or significant risk factors for the condition. Risk factors for placenta accreta include placenta previa (placenta covers all or part of the cervix), uterine scarring, prior cesarean births and, in some cases, pregnancies after the age of 35.

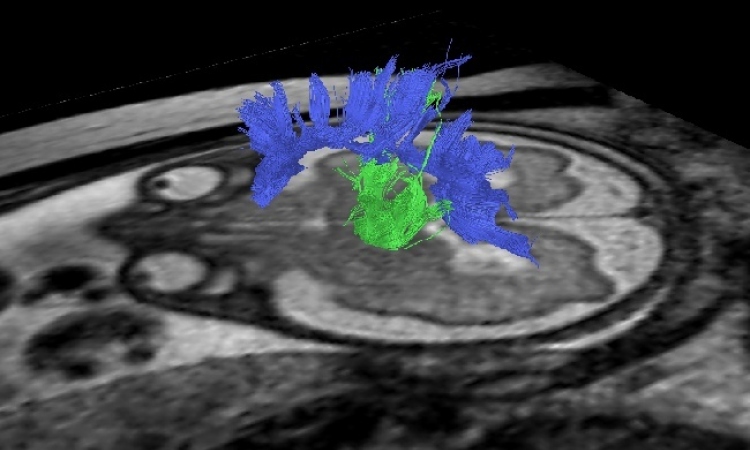

The researchers were able to compare the MR images with surgical and/or pathology results in 71 of 108 cases. When correlated with surgical and pathology findings, MRI had a 90.1 percent accuracy rate in detecting the presence of accreta. MRI does not expose the mother or fetus to ionizing radiation.

"Our findings demonstrate that MRI is an extremely useful adjunct to ultrasound for assessing this potentially life-threatening obstetric condition," Dr. Malhotra said.

A 2005 study appearing in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology analyzed data from 64,359 births over 20 years (1982 – 2002) and reported an overall incidence of placenta accreta of one in every 533 deliveries. Women who have previously delivered a baby through a cesarean section have a greater risk for the condition by a factor of three. The risk escalates with each subsequent cesarean section. According to the latest data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Center for Health Statistics, cesarean deliveries accounted for 31 percent of all U.S. births in 2006, an increase of 50 percent since 1996.

Once placenta accreta is diagnosed, a pregnancy is considered high risk, and specialists will carefully monitor a woman's prenatal care and delivery.

"Having placenta accreta is not necessarily a bad prognostic indicator for the pregnancy," Dr. Malhotra said. "It is not knowing about the condition that is potentially life threatening. Accreta needs to be diagnosed ahead of time so that delivery can be planned."

Coauthors are Lorene E. Romine, M.D., Robert F. Mattrey, M.D., and Michele A. Brown, M.D.

02.12.2009