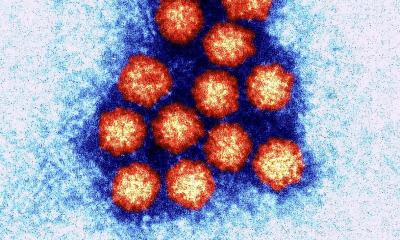

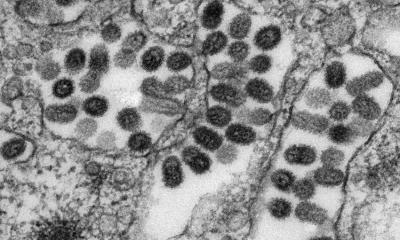

Interview • Viruses

Measles, mumps, rubella threaten youngsters

Before his presentation at ECCMID 2016, Dr Guillaume Béraud, Infectious Disease Specialist, in the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Poitiers, Poitiers, France, talked to European Hospital about the results from his modelling of these three “childhood” diseases measles, mumps and rubella.

Interview Jane MacDougall

One very real problem is because vaccination has been so successful for so long, the potential seriousness of these illnesses has been forgotten and people do not consider protection against them as a priority.

Dr Guillaume Béraud

Explaining the reason why measles, mumps and rubella were presented in the same session as viruses such as Ebola and Zika, during the 2016 ECCMID meeting, infectious disease specialist Dr Guillaume Béraud, from the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Poitiers, said this was an ‘organisational short cut on the part of the ECCMID organisers, or we could reconsider our opinion of these ‘common and benign childhood’ viral infections. Because, since the introduction of vaccination in the 1960s, these can certainly no longer be considered as “common and benign”.’

‘Also, and this is of particular importance,’ he stressed, ‘one effect of widespread vaccination – which has been extremely effective but has not, of course, achieved 100% coverage – is that these viruses have not, unlike smallpox, been eradicated. To do so, we’d need to reach 95% vaccine coverage. This has had an interesting impact on the spread of these viruses, none of which has an animal reservoir, they can only survive by infecting humans, and this is why their spread has slowed down.

‘From a modelling point of view, we can see that the circulation of the viruses is slower than in the pre-vaccine era, therefore the population being infected has changed. The population now at risk to get infected is no more children, but teens and young adults. Why? Because, in addition to the shift in age of onset due to a slower viral circulation, these are the generation that socialise the most and therefore are the most likely to come into contact with the virus and, if they have not been vaccinated, develop the disease.

‘One important downside of catching measles, mumps or rubella, when older, is that the disease is much more severe than in a younger person (<5 year old). These cases are often much more serious, with far more risk of sequelae and, in the worst case scenario, mortality and therefore, from this perspective these can certainly be considered as new emerging viral diseases.’

Why, if adequate vaccination exists, is there resurgence?

In France vaccination has been recommended for all children since 1985 and is 100% reimbursed by Social Security. The MMR vaccine requires two doses to be given before the age of 24 months. However, vaccination is not obligatory and therefore a number of children each year either receive only one, or no dose of vaccine, which enables the virus to propagate. ‘The actual vaccine coverage (which is highly variable by region) never exceed 90% for the first dose and 85% for the second dose, with much lower coverage for some departments, which is far too low for herd immunity to be protective (>90-95% is required). Therefore outbreaks can and do occur, particularly in areas where coverage is lowest, such as in south-east France. With continued suboptimal coverage the risk of epidemics can be easily be modelled – and are a real threat for 2016.

Why are vaccination rates low?

The vaccines we have are very effective and provide immunity for life and, therefore, no research has been directed towards specific antiviral therapy for measles, mumps or rubella

Dr. Guillaume Béraud

‘The reasons for low vaccine uptake are multiple and complicated. One very real problem is because vaccination has been so successful for so long, the potential seriousness of these illnesses has been forgotten and people do not consider protection against them as a priority. Also, of course, there is the anti-vaccine lobby, which is extremely articulate and convincing in its arguments and can sway a parent who has fears about vaccine safety. Of course the importance of vaccine safety is now primordial as the fear of the disease is so low.

‘As a profession, healthcare providers need to learn to communicate our message to the public in an equally meaningful way, we need to learn what triggers a mother to have her baby vaccinated. It most certainly is not the highly scientific data that excites us, and our colleagues!’

In this 21st century, why are these viral diseases potentially dangerous?

‘These diseases are entirely preventable by vaccine. The vaccines we have are very effective and provide immunity for life and, therefore, no research has been directed towards specific antiviral therapy for measles, mumps or rubella. Today, our standard of care for patients with these infections is much as it was in the 1950s and ’60s, when epidemics were frequent in the under 5s, meaning standard symptom control; fluids, rest, control of fever etc. This also means that, with the more severe cases we are seeing, we have no real therapeutic options, hence the real probability of serious complications.’

How might the cases in France affect European neighbours?

‘This problem is not unique to France; many other EU countries have low vaccine coverage, for example, the United Kingdom and Germany. The adolescent population also travels to other countries in groups. We had a good example of how this helps virus spread last year. A group of school children from Alsace visited Berlin and contracted measles from the children with whom they had exchanged.

‘Fortunately, for France, Alsace is a region with higher than average vaccine coverage and the number of cases soon petered out. This was fortunate because our modelling shows quite clearly how, in another region, an epidemic could easily have broken out. Measles is a highly contagious virus.’

How can this resurgence be stopped?

Dr Béraud: ‘Only by vaccination; we need to work together to eradicate these viruses. It should be possible, but will require a concerted effort from parent groups, healthcare professionals and governments working together, which is not as easy as it sounds.’

22.04.2016