Digital pathology

Although evolving as a tool in medical pathology for years, several factors have hampered its widespread use in this field. Now, a Scientific American article asserts that the time has come for a digital imaging revolution.

Digital images can now be used in a few ‘niche’ applications, such as making primary diagnoses, offering second opinions through telepathology and allowing archiving and image sharing. However, cost, technical factors, and pathologists who fear the advances of technology have hindered widespread use of digital pathology. According to Dr Liron Pantanowitz, those drawbacks can be overcome: ‘These are exciting times in pathology. New technologies are available; they are exciting and can be used now.’

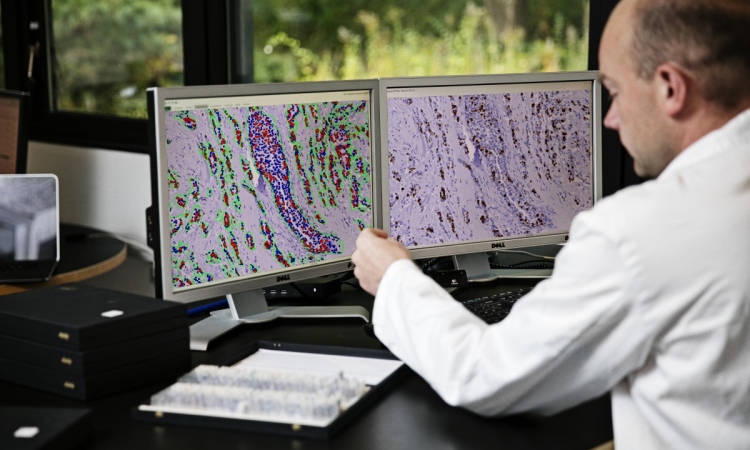

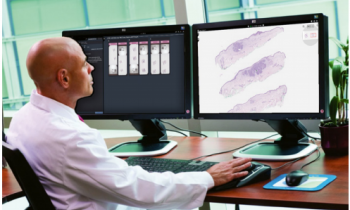

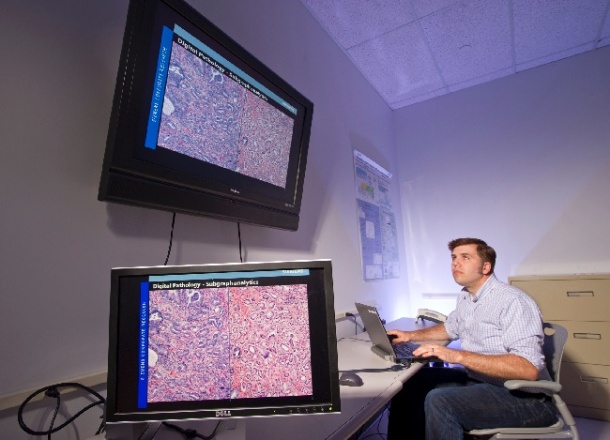

Digital images of medical samples are composed of pixels that are converted to binary code so that they can be stored at high resolution online. Although the four steps (image capture, saving, editing, and viewing) are clearly defined, none of them have been standardised, which makes them more time-consuming and the results less reliable. While whole slide imaging (WSI) has advantages in being more interactive and easy to share, it still has drawbacks, unable to completely overcome certain limiting factors, such as thick smears and 3-D cell groups in cytopathy. The FDA has not yet approved digital pathology for diagnostic purposes. ‘Some feel the equipment is too expensive,’ Dr Pantanowitz explained. ‘Others simply have technophobia and don’t want this new advance to become the gold standard. Still others just don’t want to change the way they practice, even though it may be vastly for the better.’

Digital pathology has already been shown as valuable in certain clinical settings, such as cytopathology, to help differentiate and classify morphologically similar lesions. Many institutions have come to recognise that it is easier to deliver a biological image for a second opinion across rural areas than to deliver the patients across hundreds of miles. ‘This is true in areas like Canada, where vast expanses separate major medical centres,’ he pointed out, adding, ‘They are finding ways to assure high-quality images by regulating restrictions.’ With a glass slide, you can scan in, he explained, ‘and look at a digital image, which simulates real tissue, on a virtual microscope’.

‘We need broader use of digital pathology to clarify what can be done with the technology. Some see it as a disruptive innovation that may improve a service in a manner that the market does not anticipate. At present, we have yet to see real digital slide-based routine surgical pathology in practice.’

However, Dr Pantanowitz loves the pixel, which he believes show more information than meets the eye because it is binary. ‘Is it ready for prime time?’ he asks. ‘Yes and no; eventually the barriers will be removed and digital pathology will be broadly used to clearly visualise, share, and store images for indefinite amounts of time. The pixel shows more information than the eye, and the computer can pull the whole picture together.

PROFILE

South African born Dr Liron Pantanowitz, a pathologist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, has written more than 200 publications on all aspects of pathology. He presented his ideas on digital pathology and how it can shape medical diagnosis and treatment as keynote speaker at the Cambridge Healthtech Institute conference held in San Francisco in February this year.

04.03.2013