Delayed diagnoses result in high mortality

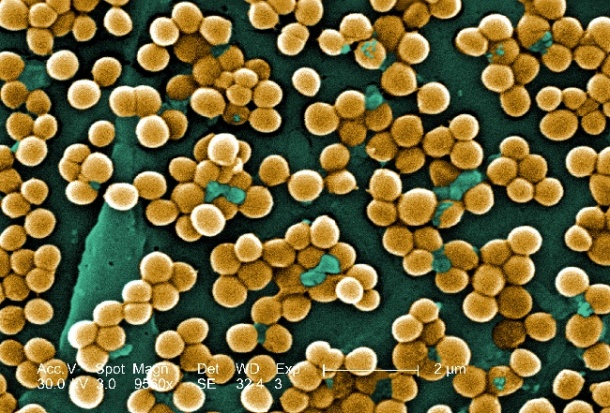

Sepsis kills around 130 patients daily In Germany alone. This systemic disease is mostly caused by bacterial pathogens, and less frequently by fungal organisms or parasites. Professor Dr Frank M Brunkhorst of the Centre of Sepsis Control and Care (CSCC), at Jena University Hospital, Germany, is seeking strategies to combat such scary figures.

With regard to, cause, spreading and consequences, in 2011 over 175,000 sepsis cases, average age 67.5 years, were treated in this country’s hospitals. 87,150 of those cases were classified as sepsis, 69,016 as severe sepsis and 18,885 as septic shock, which amounts to an incidence of 106/100,000 (sepsis), 84/100,000 (severe sepsis) and 23/100,000 (septic shock).

The numbers are rising – a trend that Brunkhorst attributes inter alia to the fact that medical progress in many areas has been leading towards more diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in increasingly older patients. Today, the number of new cases of severe sepsis and septic shock is many times higher than the number of new HIV/AIDS, colon or breast cancer cases.

A major German health insurer serving approximately 13 million clients analysed their data to calculate the hospital-related costs for patients with severe sepsis. Result: an average €59,118 per case for surviving patients and €52,101 per case for patients who died.

However, as Prof. Brunkhorst, points out, the increase of therapeutic or diagnostic interventions in older patients is not the only factor. Equally important, he underlines, are current weaknesses in microbiological diagnostic procedures and in the adequate antimicrobial therapy. The so-called SepNet prevalence study of 2004 indicated that only 55% of the infections were confirmed microbiologically, despite the presence of clinical symptoms, and a mere 9.6% of the cases were documented by a positive blood culture.

While 100 to 200 blood culture sets per 1,000 patient days are recommended; the Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe (EARS) Report 2012 (http://www.ecdc.europa.eu) shows that, in German hospitals, only 16.6 blood culture sets are taken per 1,000 patient days – a rather poor performance compared to other European countries.

Brunkhorst suggests improving sepsis diagnostics already in the pre-analytic phase (sampling technique, transportation times, etc) as well as increasing the blood culture rate. Very often, severe sepsis is diagnosed too late, since the transition from a localised infection to severe sepsis is very difficult to predict.

Early diagnosis with sensitive and specific biomarkers might help reduce mortality and morbidity. The good news is that, while many of these sepsis markers are still being researched, research, some were evaluated in clinical studies and have found their way into clinical routine.

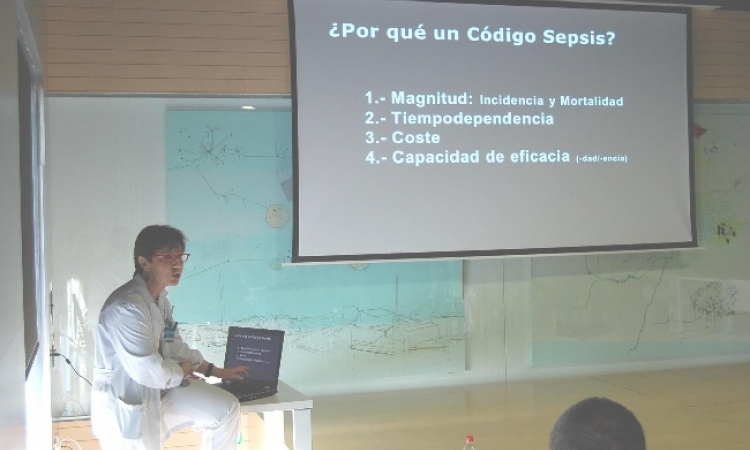

Professor Mitchell M Levy, of Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, USA, has presented a further disturbing fact about sepsis. His research indicates that, in Europe, sepsis causes more deaths than in the USA, due not necessarily to poorer European quality of care, but to structural problems that delay the identification and treatment of the disease.

According to Levy, high mortality, at least in Germany, is caused by sepsis being recognised and treated too late. He points out that up to 40% of the sepsis cases develop at home, but general practitioners rarely consider sepsis as a possible scenario and thus the patients are sent to hospital too late. Additionally, the hospital structure, with the emergency department as first point of contact, also delays ICU admission.

Professor Konrad Reinhart, Director of the Clinic of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy at Jena University Hospital, corroborates this interpretation and demands ‘better training of hospital and out-patient physicians to enable them to recognise and treat sepsis quickly’.

24.06.2014