Celebrating a 25-year-old ‘heart’

Ventricular assist devices are in a continuous evolution

Report: Michael Krassnitzer

Initially meant to bridge the gap before a heart transplant is performed, today ventricular assist devices (VADs) are increasingly considered ‘a lasting therapy option’, according to Professor Heinrich Schima, Head of the Centre for Medical Physics and Biomedical Technology at the Medical University of Vienna.

Donor organs are scarce and the number of transplants is decreasing, despite the increasing number of patients with heart insufficiency. Additionally, patients are often so content with ventricular assist devices that they want to keep them. ‘We now have patients who actually refuse transplant surgery,’ said Professor Georg Wieselthaler of the Clinical Department for Heart Surgery at the Medical University of Vienna and Medical Director of the Vienna Artificial Heart Programme.

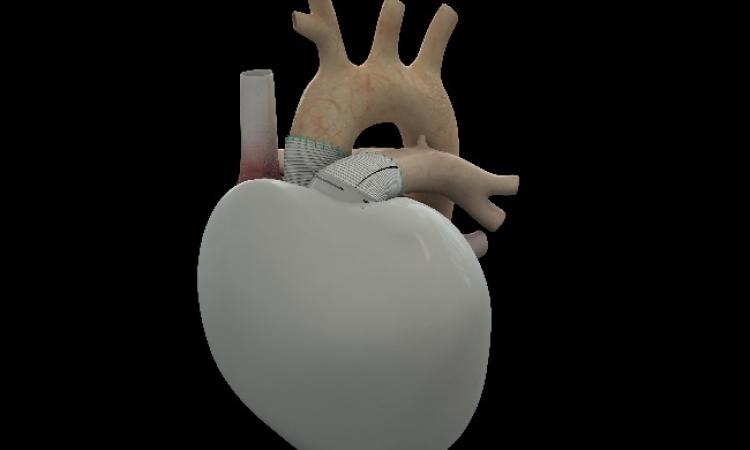

Vienna has a long tradition in cardiac surgery and ventricular assist devices and the Medical University is currently commemorating the 25th anniversary of its pioneering ‘New Vienna Heart’ procedure, first used in 1986. This artificial organ, a pulsating membrane and valves modelled on the heart, was implanted as a total cardiac replacement.

In the meantime, the procedure has evolved: the diseased heart is left in the body as a ‘safety backup’ (Schima) while a support pump (in most cases) is inserted into the left ventricle to undertake that cardiac function. Rotary pumps with up to 30,000 rotations per minute are used, as well as centrifugal pumps that move the blood by centrifugal force, and axial pumps with a similar design to that of turbines.

‘Due to liability considerations, we were no longer permitted to use devices designed in-house after the use of the first New Vienna Heart,’ Prof. Wieselthaler pointed out. However, the Medical University of Vienna has remained an important partner in ventricular assist devices development.

The world’s first patient to be fitted with a continuous-flow rotary blood pump was discharged from hospital in 1999. In 2006, the first rotary blood pump with hydromagnetic contact-free bearings was implanted in Vienna, and, since then, 300 have been implanted there – currently 35 patients are using the system. The two-year survival rate is 85%, which compares favourably with the best international results. ‘Vienna,’ said Prof. Wieselthaler proudly, ‘is one of the three leading heart support centres worldwide.’

Currently the Vienna researchers are developing new components, evaluating new systems and optimising existing ventricular assist devices. A new cannula is currently also being developed for a new generation pump. This will collect blood from the heart without causing blood clots.

A study is investigating the systems’ user friendliness and ease of use to ensure intuitive operation. Other developments include the examination of control algorithms for an adaption of the pump output to the respective physiological requirements, as well as the development of diagnostic parameters for the continuous recording of the remaining heart function.

Miniaturisation is the main theme for the next generation of VADs. ‘These systems are likely to be just thumb-size and implantation will be carried out via a cut of only 10 cm between the ribs,’ Prof. Schima predicted and, Prof. Wieselthaler added, these should be ready for clinical use within two to three years.

Cardiac research in Vienna meanwhile goes far beyond ventricular assist devices. Both professors and their team are part of the Ludwig-Boltzmann Cluster for Cardiovascular Research, which is comprised of four institutions. Current research projects deal with the connection between fatty tissue and cardiovascular disease, protection of the heart during cardiac surgery, the use of stem cells to treat cardiovascular disease and the development of new, small-calibre vascular prostheses.

Image Source: MedUni Wien

14.06.2011