Health Apps

Can medical apps replace conventional medical diagnostics?

The question as to whether or not there is a point in using medical apps on private smartphones is being asked more frequently. Issues around medical diagnostics are among the key points here. We asked Prof. Dr. Dr. Norbert Gässler, Head of the Centre for Laboratory Diagnostics at the St. Bernward Hospital, Hildesheim, for competent advice.

Interview: Walter Depner

28.8 million mobile telephones were sold in Germany in 2014, with 82% of these being smartphones. For this reason, the medical apps market has also increased exponentially. A survey by the health insurer IKK showed that 22% of Germans are already using these apps and that a further 24% intend to install them on their smartphones or tablets. What is your opinion on this?

The most popular apps are those which provide quick information on diseases and their symptoms, or those with different types of reminder functions such as for taking medication, doctor’s appointments etc. Of particular interest are the medical-diagnostic apps used to control blood pressure, body weight, body temperature, pulse, blood sugar levels and other laboratory results. For skin diseases such as malignant melanoma for instance, photographic documentation is very helpful in the assessment of the progression of the disease. There are also apps available for these types of diseases which calculate probabilities to predict malignancy with the help of algorithms. However, various studies have proven that these apps actually deliver false negative results in up to a third of cases.

In other words: They are not (yet) suitable as “diagnostic tools”. On the other hand, can those apps which are promoted as simple and practical medical aids not also be useful? Would it not be practical for instance if we were able to put a plastic foil over the phone and blow into it after the consumption of alcohol and before driving home?

Yes, this has already been trialled. But the blood alcohol content shown on the display is not precise enough, so we can only advise against this. Generally, the advice should be not to drive at all after alcohol consumption. Your conclusion that “diagnostic” apps are not (yet) suitable should be looked at with a little more differentiation. Simple measurements of blood sugar- and lactate levels are already becoming quite precise. But unfortunately these apps were not compared or validated with the methods used in precise laboratory medicine.

Back to medicine. A very common problem, particularly amongst women, is cystitis. An app currently available makes it possible to take a picture of a urine test strip which can be purchased in pharmacies. The display then detects the disease based on the different colours and patterns of the different test fields. Would this not be useful?

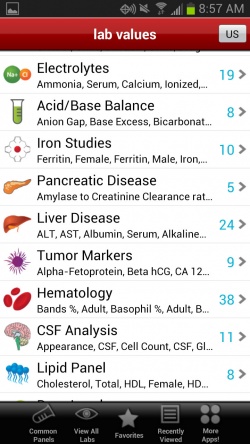

And then maybe another app for the medication? No, this approach can only be described as negligent. Clinical symptoms and scientifically sound diagnosis of pathogens are the fundamentals of precise medical treatment. Out of the more than 100,000 apps which promise medical benefits there is only a small number of medical applications with measuring functions. These however make up a large percentage of the turnover of these apps (in 2012 it was around €350 million worldwide). As shown using the example of the diagnostic procedure for cystitis, additional products such as urine test strips are often required. Some apps don’t require additional products and can be directly used with the smartphone functions. This includes hearing- and eye tests to determine responsiveness.

There is a booming market in apps which require external sensors for different types of measurements. These sensors can often be directly connected to the smartphone. This includes apps for the measurement of electric currents in the heart via ECG, blood pressure measurements (with a blood pressure cuff), the pulse (with a finger cover), current blood glucose concentration, but also more specific diagnostic markers. The latter include the measuring of TSH for the diagnosis of thyroid problems, the measuring of HIV for the diagnosis of AIDS and the measuring of syphilis for the diagnosis of sexually transmitted diseases. What do you think of this development?

The portfolio of such apps seems to be unlimited. In the USA, a first prototype for measuring blood sugar concentrations without taking blood was introduced in February 2015 in the shape of a tattoo which can be applied to the skin. The continuously measured glucose concentration levels are wirelessly transmitted to the smartphone and then documented. The boom in these medical apps is mostly occurring in the USA and Asia, but we must assume that this rapid growth will soon also reach Europe.

Should we not scrutinize the issues of data security, patient protection, ethical and legal problems and many more at this point?

Yes, correct! These apps are often heavily promoted, but with how much reliability the provider delivers the diagnostics or other services remains a bit of a grey area. And can we trust them to safeguard our personal data? This requires more than a mere call for more legal guidelines. On the other hand certain apps really can be very useful for special applications and situations. Specialists in tropical diseases for instance have been working on using smartphones with special camera add-ons as microscopes for years. There is currently a field trial in Tanzania where a modified smartphone is being used as a detection system for parasites, and particularly worms, in stool samples. The above mentioned detection of HIV but also of Malaria and other diseases could be a major argument for the use of such apps in third world countries or other areas with a lack of infrastructure.

So a plea in favour of apps after all?

The users and manufacturers of these apps should definitely work together with medical specialists and diagnosticians on the development of “useful” apps. Furthermore, interdisciplinary teams should develop sensible workflows from the capture and transmission of measurements to the resulting diagnostic and therapeutic consequences.

11.04.2015