Article • Spreading quality pathology in Canada

Building a telepathology network

Following success of telepathology in the eastern region of Quebec, the service is set to be further expanded across its remote areas. There are also moves towards a fully digital service at some sites, to introduce tele-autopsy into remote regions and extend the geographical coverage further across the region.

Report: Mark Nicholls

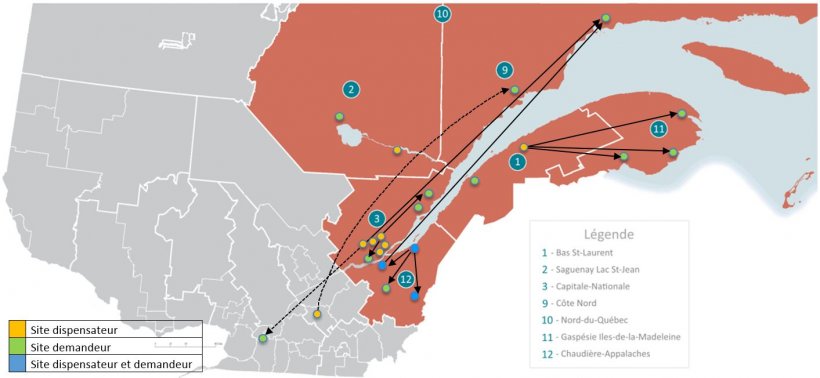

The latest developments were outlined at the Digital Pathology and AI Congress in London by Dr Olivier Michaud, anatomic-pathology resident at the Université Laval, Canada, in his presentation ‘The Eastern Quebec Telepathology Network: Eight years of improved quality pathology services in remote regions.’ This network was created in 2004 through public funding and implemented in 2011 in 20 sites, to provide access to diagnostic telepathology services to a population of 1.73 million people dispersed over 452,000/km2.

The main objectives were to provide pathology coverage in the Eastern Quebec territory and bring patient-centred pathology closer to communities. Prior to that, a lack of pathology services often led to delays in surgery, two-step surgeries, and patients being transferred long-distance. There were also difficulties in recruiting pathologists. ‘In some departments there was only a part-time pathologist, or none at all, and the schedule of operations was dependent on the availability of a pathologist,’ Michaud said. ‘From a pathologist’s perspective, there was insecurity in working alone, especially in early practice. It was impossible to rapidly obtain a second opinion and with immunochemistry performed in university hospitals, there were delays in getting the slides back.’

The telepathology network was established with several key objectives: to prevent interruption of frozen section service in laboratories with no pathologist on site; to prevent two-stage surgeries and patient transfers; to facilitate recruitment and retention of surgeons and pathologists in remote hospitals, and to reduce professional isolation and insecurity among pathologists who work alone. In Eastern Quebec, 24 sites with seven hospitals are without a pathology laboratory, 17 with a laboratory, five with no pathologist, five with one pathologist and seven with two or more pathologists. ‘It’s a decentralised network,’ he said, ‘so not all consultations go back to Quebec City.’

The network now enables expert opinion, intra-operational consultations, urgent biopsies, neuropathology, macroscopy supervision and has a tele-autopsy capability. Each site is equipped with a macroscopy station, video conferencing devices, a drawing tablet, and a digital whole slide scanner with images saved on a dedicated telepathology server. The macroscopy station and video conferencing device allow the pathologist to interact with the surgeon and once the selection of the sample is completed, a technician proceeds to cryo-sectioning and staining. ‘The slide is scanned and sent to receiving centre for analysis by the pathologist,’ Michaud explained. Using designated software, the pathologist can read the clinical information, examine whole slide images and also dictate or type a final report. Macroscopic supervision covers colectomies, hysterectomy, mastectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, thyroid and parathyroid, lung lobectomy, dermatopathology excision for melanoma, other gastro-intestinal resections and genitourinary work.

In an average month, the network saw 164 slides scanned for primary diagnosis (including urgent interpretation) and with a maximum of 792; 39 for intraoperative consultations; 49 for expert opinions between pathologists, 35 for assistance to macroscopic description, with 631 slides scanned for teaching purposes. Michaud added that the workload is outside the normal caseload and usual practice of the pathologist.

We are looking at tele-autopsy for remote regions, so the body does not have to be transported to Quebec – and we are already doing that for educational purposes

Olivier Michaud

When sent for expert opinion, the average turnaround time was 32 hours, with 38.5% completed in 12 hours. With frozen sections, 98.1% were concordant and average turnaround time was 20 minutes, compared to 15 minutes when a pathologist was on site before. Michaud explained that the service had proved successful with the key objectives achieved: interruption of frozen sections were prevented, there was a reduction in two-stage surgeries and patient transfers, recruitment and retention issues were improved, and professional isolation and insecurity among pathologists reduced.

However, Michaud acknowledged that challenges and barriers remain, with surgeons having to adjust to asking for the service, different work patterns, and the need for mutual confidence and trust between centres and personnel. There was also the need to adapt workflow, archiving, integration with local LIS, issues of prioritising telepathology over in-house cases and reimbursement and also legal issues to be resolved.

Yet, there are now plans to expand to other regions in Quebec and fully digitise laboratories at selected sites. ‘We are looking at tele-autopsy for remote regions,’ he pointed out, ‘so the body does not have to be transported to Quebec – and we are already doing that for educational purposes.’

Profile:

Olivier Michaud is a chief resident for the Anatomic Pathology Training Program at Université Laval, in Quebec City, Canada. His main research focuses on digital pathology implementation in public funded systems, as well as in breast pathology and the implementation of new targeted therapies in breast cancer treatment.

13.07.2020