Beyond FAST!

Whole-body ultrasound emerges in critical care and emergency medicine

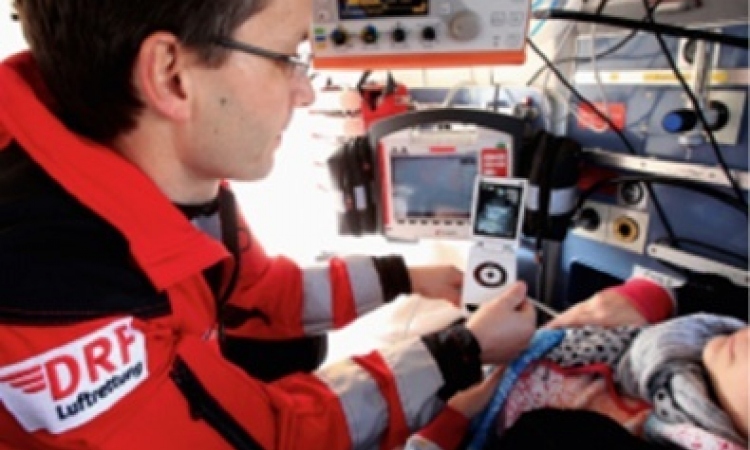

Loading high performance functions on highly portable ultrasound systems puts life-saving tools in the hands of trauma physicians, John Brosky reports.

Scanning the entire body of a trauma patient has proven critical for detecting unseen injuries and whole body CT scans are routinely performed in emergency departments – when available. Thus physicians are increasingly turning to the always-ready, easily accessible and more affordable ultrasound systems for a rapid, yet comprehensive assessment of injured patients. ‘I’m a pre-hospital physician and ultrasound enables me to detect and even treat a patient on-site, in his apartment, even in the car at the accident scene,’ explained Dr Tomislav Petrovic, from the Urgent Ambulatory Services 93 group (SAMU) 93, which covers the North- Eastern Paris suburb of Seine-Saint Denis from the Hôpital Avicenne in Bobigny.

‘Looking at a patient you can see a particular area of concern, but ultrasound allows you to rapidly look beyond this to conduct a wider, holistic assessment of how the patient’s system is reacting to the trauma,’ he said, however adding that the examination does not replace a CT scan. Instead, ‘the advantage of ultrasound is you can do it right now at the point of care. ‘Physicians no longer consider ultrasound as complementary examination,’ he pointed out. ‘It is going to be completely integrated in the physical examination where physicians use their hands, ears and eyes to gather all signs on patient.’ Ultrasound becomes an extension of the physician’s eyes just as the stethoscope amplifies the observational power of the ears, and the ultrasound probe is becoming as familiar as the stethoscope in routine examinations.

‘Ultrasound can change not only the diagnosis but also the treatment and final orientation of the patient,’ he said. ‘This is what we call Critical Ultrasound, and this is what we are increasingly doing in emergency departments today.’ Ultrasound won a valued role in emergency with the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) rapid exam to determine if there is blood or liquid around the heart or abdominal organs. Originally called focused abdominal sonography for trauma, the exam was upgraded as a fuller assessment as physicians recognised the probe could also visualise injuries in the thorax well before a CT scan, detecting inter alia an otherwise occult pneumothorax, a deadly complication if not treated immediately.

Dr Petrovic said that, thanks to advanced capabilities available on portable systems, ultrasound is now being applied beyond the extended FAST (eFAST) examination to cover the entire body. ‘A patient is not just an abdomen or a thorax, and a physician’s focus is not just the immediate disease but the whole patient,’ he explained. ‘In many cases, ultrasound allows the physician to instantly go from saying, I don’t know what to do, to saying I know and I will do.’

A classic case, he said, is the patient who arrives in the emergency department complaining of chest pain. If a physical exam complemented by an electrocardiogram (ECG) shows there is an acute myocardial infarction, the patient is immediately selected for reperfusion, whether chemical (thrombolysis) or mechanical (angioplasty).

What happens more often, he said, is that neither the physical exam nor the ECG are conclusive. ‘Here you do not know what is happening and an ultrasound exam can rule in or rule out a range of pathologies, whether cardiac, pulmonary, or forensic,’ he said. ‘We often see cases where a patient had a thorax injury (e.g. fall off his bicycle) several days before and simply does not remember to mention it,’ he explained. ‘Now he has a chest pain. With ultrasound we can visualise a fractured rib or sternum. We can see if there is any pneumothorax or pleural effusion, which are not always visible on a chest X-ray.’

There are ultrasound exams used to assess bone fractures, especially for long bones and flat bones, he said. More recently transcranial Doppler also became available to assess blood flow in the brain for cranial trauma ‘immediately, while we can do things to improve the survival of the patient, rather than waiting three or six hours to insert a device to measure intra-cranial pressure. This is point-of-care ultrasound and it’s not a one-shot image,’ he emphasised, contrasting it with ultrasound performed in the radiology lab that he called ‘out-of-care’ imaging, where a patient is transported and left for a specialised examination.

‘At point of care, at the bedside, in a hospital or at a trauma scene, we may look at the chest, then a cardiac exam, certainly some abdominal, perhaps lower limb veins,’ he said, adding that systems offer functions such as TM mode, colour Doppler, pulsed wave or continuous wave Doppler. ‘These are focused exams, designed by ER physicians, with a precise protocol to give actionable information in a few minutes. For example, I don’t need to know which organ is bleeding in the abdomen; I need to know if there is haemorrhage.

‘When I place the probe I get the information I need, telling me if I need to send the patient directly to the operating room or not, if there is time to send him for a CT scan, or some other test to know more precisely what is happening.’

Profile

Tomislav Petrovic MD, emergency physician and specialist in pre-hospital critical care, is a passionate advocate of training and education to integrate ultrasound as a tool to assess and monitor the care of patients. From 2011-2012 presided over WINFOCUS, the World Interactive Network Focused On Critical Ultrasound, a professional society dedicated to improving primary, emergency and critical care medicine with ultrasound. He is also a contributing editor for Critical Ultrasound Journal and a regular speaker at congresses worldwide.

26.04.2013