Article • Custom parts made in the lab

3D printed implants on demand

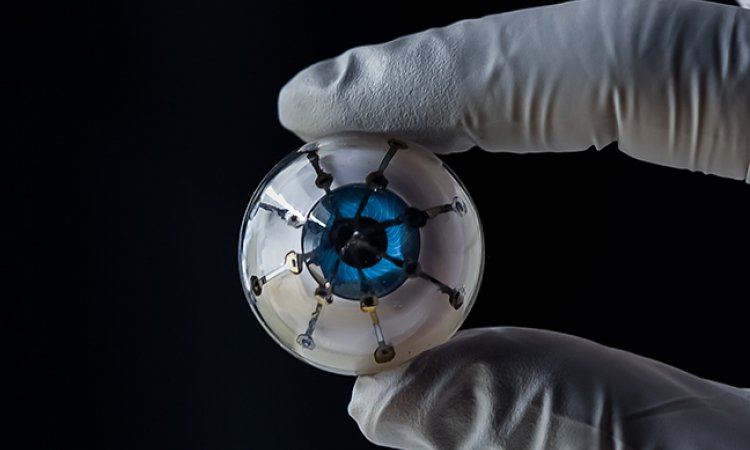

A custom-made new hip, a knee or maybe a piece of bone? The technology and possibilities for 3D printing are (almost) there. And such an implant from a 3D printer has many advantages, not only for the patient, but also for the surgeon who has to perform the operation. Koen Willemsen, physician, and medical engineer at the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU), was at the cradle of the 3D lab at the UMCU where 3D implants, as well as surgical drilling and sawing jigs, are printed on demand.

Report: Madeleine van de Wouw

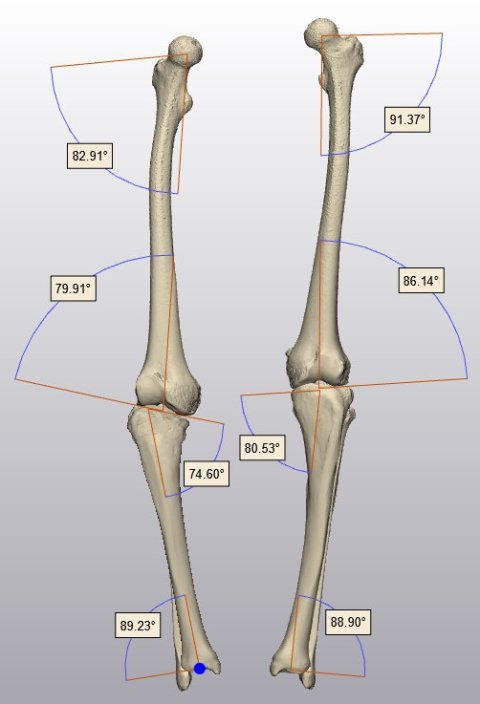

3D printed implants have a large benefit to both physicians and patient. For patients for whom standards implants don’t work, the very precisely calculated technology of creating a 3D model sometimes literally makes the difference between not walking or walking again. The advantage for doctors is that by using a 3D template of the affected area, they know exactly where to make the incision during surgery and what the exact location of the implant will be. This accuracy is further enhanced by the application of augmented reality (AR), in which Willemsen's 3D lab is also a pioneer.

Enhanced accuracy

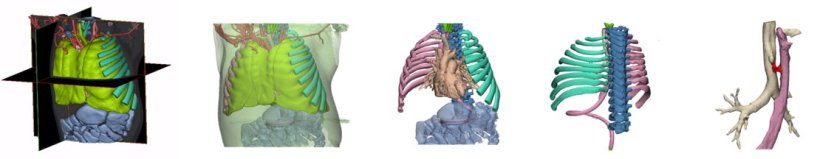

Doctors place an order for the 3D/AR visualization. Willemsen: ‘Using AR glasses in the lab, doctors are able to see on a computer screen exactly what a patient's inside looks like. We guide then through the operation. They can "walk around" the 3D model of the patient, and practice implant placement. This also helps to prepare before surgery, saves quite some time and is an assurance for quality. Therefore, we sell this as a sustainability option. We have been working with AR for six months now and our intern students are developing the protocols, conditions and are looking into how to make it even more accurate. Everything has to be placed correctly because mistakes are easy to make. For instance, in another center, they had made a 3D model, but measured it incorrectly. The surgeon therefore used the wrong cut-off point because the aneurysm was actually smaller than calculated. Accurate measurements and requirements could have prevented this. And that’s why quality management and risk analysis are so important.’

Safety measures and guidelines

Users also need to be aware of the legal boundaries, cautions Willemsen: '3D printing opens a lot of possibilities, but must comply with all kinds of safety measures. Here too, we play a pioneering role because at the moment, only few hospitals are able to produce 3D prints in compliance with the current Medical Device Regulation legislation (MDR) that’s in place for just over a year now. We co-developed the requirements for the MDR, which now describes techniques and safety issues in a well-founded system. Before 2021, there were really only advisory guidelines for developing medical implants and devices. Ignorning those guidelines was not punishable, and things went wrong quite often. For example, even tangerine packing nets could be approved as pelvic floor mats.'

We need to make 3D printing rationally applicable to other hospitals by properly defining design rules and rationales. Ensuring safety, sharing records. We want to prevent cowboy behavior, which is why requirements and protocols are so important

Koen Willemsen

Such questionable practice was among the reasons for Willemsen to take 3D printing to a safe level in their lab for both the procedures and the materials used. ‘In our hospital, we take the international ISO standards for quality management (ISO 13485) as a starting point so that everything is done properly and safely. MDR is a dynamic system, because of ongoing developments, for example in the use of materials. Until 2016, titanium was the most common material for 3D printed implants. Now there are many more materials, like PEEK (polyetheretherketone), which is a powerful thermoplastic material with very low moisture absorption and good dimensional stability. We make all the implants ourselves according to the International ISO 13485 standard. Because research into bone replacement materials is ongoing, users need to go a step further in the quality of the management system and prove the safety of the new materials before they may be used in a patient.’ The 3D model is created from the MRI scan by selecting and segmenting the appropriate organ on each slice, which determines how and where operations can be performed best. A 3D model can also be of great help in paediatric surgery. Willemsen: ‘For example, the scan of a child shows that there is a fistula somewhere behind the heart. The 3D model of the scan shows the exact location, allowing to operate in a much more focused way and determine the exact spot of the fistula.’

The future

Future plans include printing bones, cells and various tissue types. Bones consist mainly of calcium and phosphate and are relatively easy to recreate via 3D printing. Because of this, application in humans is already waiting in the wings. The composition of cartilage is much more complex, let alone printing a kidney or heart. Willemsen: ‘We already have the first results of tissue prints, now being done in animal research. Next, we need to translate that to humans. I expect to see the first results in the next few years.’

He emphasizes that removing, of spreading open the bone, is the main treatment. 3D Bone implant placement is secondary and can speed up recovery. ‘Because we also make drilling and sawing jigs of the affected bone, the surgery, both the removal and placement of an implant, can be much more successful and accurate. The cost of 3D printed bone replacement structures is significantly below the price tag of actual bones. For example, the Dutch bone bank charges € 5000 for a femur.'

Willemsen: ‘We are at the beginning of these developments and are setting up a European Special Interest Group for 3D devices. The first meeting has already taken place in the summer of 2022. We need to make 3D printing rationally applicable to other hospitals by properly defining design rules and rationales. Ensuring safety, sharing records. We want to prevent cowboy behavior, which is why requirements and protocols are so important. At the moment, we can only treat the happy few with 3D models, but with wider adoption it will become available to many more people.’

Profile:

Koen WIllemsen started his medical studies at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. After graduation in 2016, he was awarded a PhD position and worked as a medical doctor and PhD student as part of a large consortium in which novel 3D-printed implants and MRI-based diagnostic tools were developed. In 2019, he co-founded the UMCU’s 3D lab. In 2020, he started a post-graduate traineeship as a Qualified Medical Engineer at the Technical University Eindhoven next to his work as 3D lab coordinator to further professionalize the 3D lab and work towards his Doctor of Engineering degree.

16.11.2022