Image source: Brandon Martin/Rice University

News • New method

Time-released drug delivery could make vaccines last for months

Missing crucial doses of medicines and vaccines could become a thing of the past thanks to Rice University bioengineers’ technology for making time-released drugs.

“This is a huge problem in the treatment of chronic disease,” said Kevin McHugh, corresponding author of a study about the technology published online in Advanced Materials. “It’s estimated that 50% of people don't take their medications correctly. With this, you’d give them one shot, and they’d be all set for the next couple of months.”

When patients fail to take prescription medicine or take it incorrectly, the costs can be staggering. The annual toll in the United States alone has been estimated at more than 100,000 deaths, up to 25% of hospitalizations and more than $100 billion in healthcare costs.

Image source: Brandon Martin/Rice University

Encapsulating medicine in microparticles that dissolve and release drugs over time isn’t a new idea. But McHugh and graduate student Tyler Graf used 21st-century methods to develop next-level encapsulation technology that is far more versatile than its forerunners.

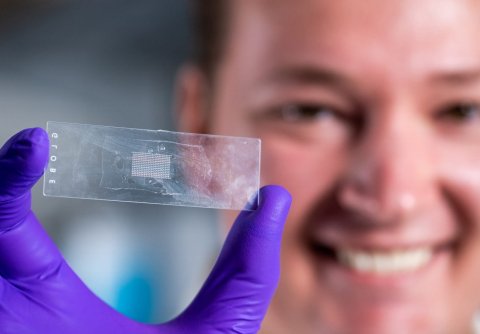

Dubbed PULSED (short for Particles Uniformly Liquified and Sealed to Encapsulate Drugs), the technology employs high-resolution 3D printing and soft lithography to produce arrays of more than 300 nontoxic, biodegradable cylinders that are small enough to be injected with standard hypodermic needles.

The cylinders are made of a polymer called PLGA that’s widely used in clinical medical treatment. McHugh and Graf demonstrated four methods of loading the microcylinders with drugs, and showed they could tweak the PLGA recipe to vary how quickly the particles dissolved and released the drugs — from as little as 10 days to almost five weeks. They also developed a fast and easy method for sealing the cylinders, a critical step to demonstrate the technology is both scalable and capable of addressing a major hurdle in time-release drug delivery.

Image source: Tyler Graf/Rice University

“The thing we’re trying to overcome is ‘first-order release,’” McHugh said, referring to the uneven dosing that’s characteristic with current methods of drug encapsulation. “The common pattern is for a lot of the drug to be released early, on day one. And then on day 10, you might get 10 times less than you got on day one. If there’s a huge therapeutic window, then releasing 10 times less on day 10 might still be OK, but that’s rarely the case. Most of the time it’s really problematic, either because the day-one dose brings you close to toxicity or because getting 10 times less — or even four or five times less — at later time points isn’t enough to be effective.”

In many cases, it would be ideal for patients to have the same amount of a drug in their systems throughout treatment. McHugh said PULSED can be tailored for that kind of release profile, and it also could be used in other ways.

“Our motivation for this particular project actually came from the vaccine space,” he said. “In vaccination, you often need multiple doses spread out over the course of months. That's really difficult to do in low- and middle-income countries because of health care accessibility issues. The idea was, ‘What if we made particles that exhibit pulsatile release?’ And we hypothesized that this core-shell structure — where you’d have the vaccine in a pocket inside a biodegradable polymer shell — could both produce that kind of all-or-nothing release event and provide a reliable way to set the delayed timing of the release.”

Image source: Brandon Martin/Rice University

Though PULSED hasn’t yet been tested for months-long release delays, McHugh said previous studies from other labs have shown PLGA capsules can be formulated to release drugs as much as six months after injection.

In their study, Graf and McHugh showed they could make and load particles with diameters ranging from 400 microns to 100 microns. McHugh said this size enables particles to stay where they are injected until they dissolve, which could be useful for delivering large or continuous doses of one or more drugs at a specific location, like a cancerous tumor. “For toxic cancer chemotherapies, you’d love to have the poison concentrated in the tumor and not in the rest of the body,” he said. “People have done that experimentally, injecting soluble drugs into tumors. But then the question is how long is it going to take for that to diffuse out. Our microparticles will stay where you put them,” McHugh said. “The idea is to make chemotherapy more effective and reduce its side effects by delivering a prolonged, concentrated dose of the drugs exactly where they’re needed.”

The crucial discovery of the contactless sealing method happened partly by chance. McHugh said previous studies had explored the use of PLGA microparticles for time-released drug encapsulation, but sealing large numbers of particles had proven so difficult that the cost of production was considered impractical for many applications.

While exploring alternative sealing methods, Graf noticed that trying to seal the microparticles by dipping them into different melted polymers was not giving the desired outcome. “Eventually, I questioned whether dipping the microparticles into a liquid polymer was even necessary,” said Graf, who proceeded to suspend the PLGA microparticles above a hot plate, enabling the top of the particles to melt and to self-seal while the bottom of the particles remained intact, “Those first particle batches barely sealed, but seeing the process was possible was very exciting.”

Further optimization and experimentation resulted in consistent and robust sealing of the cylinders, which eventually proved to be one of the easier steps in making the time-released drug capsules. Each 22x14 array of cylinders was about the size of a postage stamp, and Graf made them atop glass microscope slides. After loading an array with drugs, Graf said he would suspend it about a millimeter or so above the hot plate for a short time. “I’d just flip it over and rest it on two other glass slides, one on either end, and set a timer for however long it would take to seal. It just takes a few seconds.”

This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR190056), the National Institutes of Health (EB031495, EB023833) and the National Science Foundation (1842494, 2236422).

Source: Rice University

02.07.2023