TELEMEDICINE ADVANCES IN EUROPE

SCOTLAND

A promising pilot project

Cardiac patients in a remote Scottish area are having their condition assessed in a unique telemedicine project. The Argyll and Bute Telecardiology Project is collaboration between the Argyll and Bute Community Health Partnership (CHP) in the far west of Scotland and Cardiology Services at Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

Set up in May this year, with support from the Scottish Centre of Telehealth (SCT), patients who suffer suspected heart insufficiency, have chest paints or develop a range of other heart problems can be assessed remotely and quickly at a cardiac clinic at the Mid Argyll Hospital in Lochgilphead, which is linked via video conferencing to a consultant cardiologist in Glasgow.

Early signs from the pilot project indicate that patients are being effectively and cost efficiently assessed, without the stress of having to travel 145 km from their remote area to Glasgow.

James Ferguson, lead clinician with SCT said: ‘With the telecardiology initiative, patients can undergo tests and be assessed; we can institute treatment early and decide if they are going to need simple drug treatment or get them to Glasgow for a more detailed examination and angiography. It will hopefully mean we can more efficiently select those patients that need to come into hospital.’

Within the fortnightly telecardiology clinic, a trained cardiovascular nurse will facilitate and coordinate the clinic and ensure that all appropriate tests are completed. Exercise tolerance tests, echocardiography and ECG testing would be carried out by a cardiac physiologist at the community hospital, with cardiovascular nurse assistance during the clinic.

Following testing, the cardiovascular nurse will link by video conferencing, with the Consultant Cardiologist at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, enabling all the team members to view and discuss the patient, their results and the next treatment stage. If required, the cardiologist can see the patient in Glasgow for further discussions, treatment or diagnostic assessment.

The first clinic was held on 15 May; by the end of July, eight patients had been seen in this way at Lochgilphead, saving almost 2,000 km of travel.

An evaluation of the new service will be conducted at the end of the first year, reviewing patient numbers, outcomes and patient travel to Glasgow. However, Mr Ferguson said the initial response to the clinics had been positive: ‘What we are trying to do is to move more cardiac care into the community. With the diagnostic tests performed it means we

can make an early assessment of the patients’ needs. After the diagnostic tests, combined with patient history, we can decide whether the patient can be managed with drugs locally or needs to go to the main cardiac centre to see a consultant or for further treatment, such as angiography.

‘Ultimately there is no reason why telecardiology cannot also be applied in the large conurbations, because moving about in the big cities can also be time consuming. Telecardiology just makes the system much more effective and makes more efficient use of specialist expertise. I think the early signs of the telecardiology project are very promising and with the economic climate facing the NHS, we are going to have to tackle inefficient practices and telemedicine is a cost-effective way of doing that.’

Telecardiology has the potential to be developed in other remote areas of Scotland (population five million). Other telemedicine initiatives being undertaken by SCT include telerehabilitation, teleneurology, telestroke and tele-endoscopy projects.

Report: Mark Nicholls

Managing home-based patients with chronic conditions

Following successful Dutch pilot studies, in which Intel collaborated with the Academic Medical Centre Amsterdam and the Institute for Prevention and Telemedicine, Intel’s in-home patient device, Health Guide PHS6000, which combines with the online interface Intel Health Care Management Suite, has been implemented by the Lothian National Health Trust (NHS), as part of a large scale, 400-unit telehealth pilot –

a collaboration between NHS Lothian and the Scottish Government, implemented by Intel and Tunstall. The pilot will begin with 200 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients and later include patients with other chronic conditions (cardiac diseases and diabetes) across Edinburgh and Lothian regions.

A number of patients included in the programme will be enrolled in a randomised control trial, to be conducted by Edinburgh University. Research results are expected in 2010.

The system’s interactive tools enable personalised healthcare management, including vital sign collection, patient reminders, surveys, multimedia educational content, plus feedback and communication tools such as video conferencing and alerts. Clinicians have ongoing access to data.

GERMANY

Remote monitoring for chronic heart disease

Cardiac insufficiency is one of the most frequent heart conditions worldwide. Estimates in Europe alone indicate that ten million people suffer some form of chronic heart disease (CHD), leading to countless hospitalisations.

Early detection of the risk factors and further improvement in quality of care are the aims of a new network. Several health insurers (DAK, Barmer Ersatzkasse, BKK ZF & Partner and BKK MTU Friedrichshafen), the Friedrichshafen hospital and Friedrichshafen general practitioners’ (GPs’) association, and Bodenseekreis, a physicians’ network, have linked up to provide integrated care for cardiac insufficiency patients in the south-western German region Bodensee/Oberschwaben.

The network is supported by health insurers and collaborators, with technology partners Philips and T-Systems providing Motiva, a telemedicine solution. T-Systems is already using Motiva in a pilot project in T-City Friedrichshafen.

‘If we recognise early on that the status of a patient suffering cardiac insufficiency is deteriorating, we can take immediate measures and thus improve his quality of life,’ explained Jochen

Wolf, acting managing director of Friedrichshafen Hospital. To do this successfully, continuous and coherent care is necessary along the entire care chain, from GP to cardiologist. ‘By detecting problems early, we aim to shorten hospital length of stays and even avoid hospitalisation entirely,’ said Peter Rowohlt, director of hospital services for health insurer DAK. ‘In Friedrichshafen, we learnt that the feeling of being monitored by a physician gives a patient a sense of safety and security. Consequently, they don’t rush to see a physician at the first sign of deterioration.’

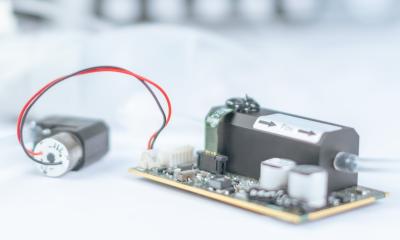

Motiva enables doctors to treat the patients in their homes. The patients regularly transmit data, such as BP, heart rate and body weight, via a TV set to the hospital, where they are continuously monitored. Whenever the data indicate a negative development, appropriate measures are immediately taken and, if necessary, the patient is hospitalised. Severely ill patients feel safer and no longer compelled to visit GPs or hospital daily.

Motiva requires only a TV set top box, broadband internet access, digital scales and blood pressure measuring equipment.

CZECH REPUBLIC

A long wait ahead for telemedicine

The estimated chronic heart failure (CHF) prevalence in the Czech republic is somewhere between 1-2% (then approx. 2.3% in the 60-69 age-group, approx. 9.1% in the 70-75 age group, and over 10% in 75+ age group) and the annual incidence is about 0.4%. If these relative numbers are taken as absolute number of Czech patients, there are some 100,000 to 200,000 patients suffering CHF – quite a number. Despite recent advances in cardiac care, CHF prognosis remains unfavourable, as evidenced by the five-year survival rate – roughly 50%.

CHF treatment for Czech patients tends to be very complex; it consists of non-pharmacology, regime, and dietary interventions plus pharmacotherapy and surgical procedures (revascularisations, device implantations - cardioverters/defibrillators, and ultimately orthotopic transplants) in specific cases.

HF economics

The high costs of CHF treatment represent a real economic burden to all health systems. In western Europe, CHF therapy consumes up to 1–2% of their entire healthcare budgets, which is very close to the Czech situation. The largest costs for CHF treatment arise from repeat hospitalisations; CHF patients account for up to 5% of all hospitalisations. In the 65+ age group, CHF is identified as the main cause of 20% of all hospitalisations in the internal medicine department. The data are clear: the number of hospitalisations for HF in the Czech Republic (as in most European countries) has increased fourfold over the last 20 years.

In reality, data from clinical trials indicate that money is the predominant limiting factor in the individual treatment of serious CHF cases that need greater intervention. First, a cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) system alone costs about ?10,000; an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) system ?30,000; both CRT plus ICD combined save no extra money as they are available for about ?40,000. Secondly, Czech clinicians are still striving for more appropriate patient selection methods that will enable improved treatment. Using today’s selection criteria, it has been said there are about one third of non-responders to the costly CRT therapy.

However, apart from direct costs, after-care expenditures for HF patients are also enormous. The Czech situation is even more complicated by the fact that any 21st century medical technique, e.g. telemedicine, is rejected by the legal environment. In practice, even highly qualified and experienced nurses cannot perform any medical interventions related to drug prescriptions, diagnoses, etc. These procedures must be done exclusively by physicians – and unfortunately doctors are famously short of time. Given their daily duties, physicians simply have no time to train in new technologies.

In reality, nurses can sometimes follow up on certain patients by phoning them, performing some basic assessments and, if necessary, informing doctors about potential problems with the patient’s clinical status. Although nurses are restricted, there are some lonely birds

out there. For instance, Nemocnice

Na Homolce (Homolka Hospital, www.homolka.cz) is running a programme associated with their Cardiocentre, which involves post-surgical patients or similar. This is advantageous because patients are well known to the hospital staff and hence a more than professional relationship may be readily established. Nonetheless, generally it appears that Czech patients, nurses and doctors must wait for some time before real telemedicine approaches arrive.

Data collection

A complex patient programme represents an integral part of Hospital Homolka Cardiocentre (HHC) and its ambulatory monitoring and treatment efforts provided to HF patients (stage NYHA II-III) of diverse aetiology. Patient population consists of patients coming in from various departments/ambulances, or from referring physicians. HHC provides complex cardiac healthcare, from simple monitoring to invasive surgery either directly or indirectly, e.g. orthotopic heart transplants are carried out at the associated medical facility – IKEM (Institute of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, www.ikem.cz).

HHC does not provide any electronic data capture system (telemedicine); all the patients must physically present themselves to the physician. However, there are efforts to launch home telemonitoring when patients are being followed by nurses by phone to check on any changes since their last visit to the centre, necessary changes to medication or regime, or any changes in their current clinical status. Based on these findings, The Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHF) is very frequently used, it is then decided if patients should visit the centre to have done any changes to their current care or performed additional diagnostic tests (echocardiography, spiro-ergometry, coronarography, Holter ECG, ambulatory BP monitoring, myocardial perfusion SPECT imaging, cardiac MRI, etc). Also, HHC personnel can arrange psychology support (psychologist or psychiatrist) or physiotherapy.

Conclusion: It is quite clear that better and modern care needs greater financial resources, but this cannot be the only side of the hill because the grass is not always greener on its other side. Medical professionals must consider that new and better ways of identifying appropriate treatment for appropriate patients need to be sought. In other words, personalised medicine affects care at all levels, not only genetic and biochemical levels (or genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics – the buzz words of today).

Report: Rostislav Kuklik

01.09.2009