New dimension

Space technology influences wearable devices

Wearable monitoring devices are offering patients the chance to play a greater and more active role in their own healthcare. They are alerting physicians and carers when a patient may be unwell, or their condition needs closely monitoring, and they have potential to improve the accuracy of findings within clinical trials.

Report: Mark Nicholls

The role of wearable healthcare was a keynote issue in a session at the EHI Live conference – the United Kingdom’s largest digital health event – held in Birmingham this November.

Chaired by Maxine Mackintosh, Chair of HealthTech Women - an organisation that aims to promote more participation by women in healthcare innovation – the event included representatives from across the National Health Service (NHS) and industry.

Deb El Sayed, Director of Digital and Multi-Channel for NHS England, explained how experiments in the 1990s to try to monitor patients remotely, such as those with COPD, had proved ‘clunky’ and relied heavily on the patient, but within the space of two decades had reached a scenario where there is the ability for continuous effective monitoring. ‘We are getting data from individuals continuously, which is giving clinicians a much broader view of what is going on,’ she explained.

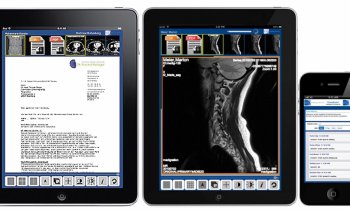

The period has seen devices become much smaller and more discreet, to the extent that there has been the development of wafer thin patches with minute circuitry and space technology developed by NASA, which is now seen in healthcare settings.

‘Wearable patches can monitor patients after surgery, using the skin as a digital platform,’ El Sayed said. ‘The next step is looking at “digestibles” that look inside the body rather than invasive procedures, such as a colonoscopy. However, with all these technologies, the important aspect is ensuring their accuracy and that adoption is evidence-based so that these systems can be used much more pervasively.’ From there, she added, it is also about addressing how that captured data is stored securely in the future.

The question of wide variability in data delivered by different devices was raised, but panel members felt that it was still better that on-going data was delivered, rather than the occasional snapshot in response to a face-to-face consultation with a general practitioner (GP) or other health professional.

El Sayed said a number of trials are taking place aimed at offering a better understanding of that data variability and to help improve accuracy.

Dr Elin Haf Davies, founder and CEO of Aparito – which uses wearables and disease specific mobile apps to deliver patient monitoring beyond the hospital - outlined how wearables can have an important role in clinical trials. ‘Using an episodic or static snapshot of the patient is not really reflective of how the patient is doing; we need to be moving towards an overall understanding of how they are doing between these assessments and that’s where a wearable really lends itself,’ she pointed out.

With rare diseases often affecting children, she suggested that assessing them consistently with traditional data gathering was more difficult because of their tender age and, consequently, a significant number of trials were showing inconclusive outcomes.

However, by making wearables smaller, more attractive and trendy, with a longer battery life and requiring no input from the patients, they could play a role in helping trial data become more consistent, particularly of that acquired in younger people. But, she did stress, ‘Wearables will not be replacing the doctors, but will be augmenting the service they offer.’

Suzanne Homewood, Samsung Enterprise Sales Director, pointed out that, whilst wearables were new to people in a healthcare setting, they were not new to them as consumers. ‘What is important is that we enable people to use their consumer experience in a health environment and from the viewpoint of improving their own health,’ she advised.

09.11.2016