Image source: generated with AI (Gemini 2.5 Flash Image)

Article • Radiology meets literature at JFR 2025

The art of healing with words

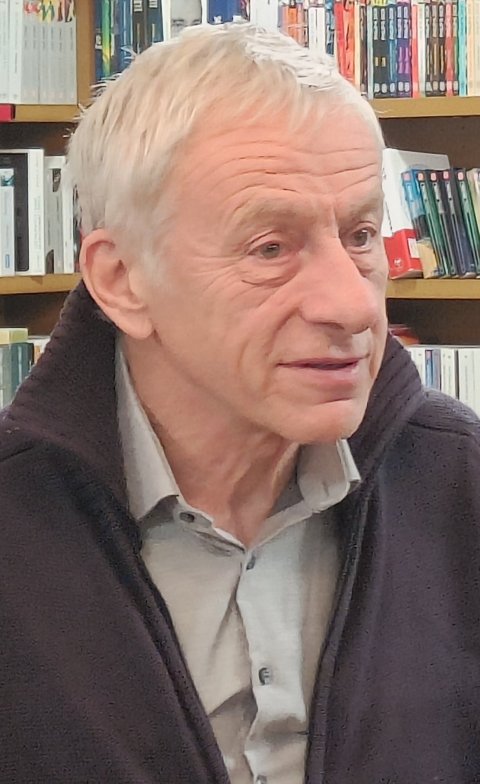

At the 2025 Journées Francophones de Radiologie (JFR), novelist, diplomat, and physician Jean-Christophe Rufin took the stage to remind an audience of radiologists that medicine, at its core, is a human story – one that needs to be told, felt, and shared. Beneath the cold light of MRI scanners and the hum of technology, he reintroduced something fragile yet essential: empathy.

By Mélisande Rouger

Before becoming one of France’s most acclaimed writers, Rufin spent years on the front lines – as a humanitarian doctor, diplomat, and activist. A former vice-president of Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières), Rufin led missions in war-torn Africa and the Middle East, and served as France’s ambassador in Senegal and to the UN.

Those experiences, marked by exhaustion, loss, and hope, shaped the writer he would later become. ‘In extreme situations,’ he recalled, ‘the body tells the truth first. The doctor listens with their hands, but the writer listens with their heart.’

Image source: Bruno Barral, JCRufinVincennes02 (CC BY 4.0)

His novels – from “The Abyssinian” to “Globalia”, from “Check-point” to “Brazil Red” – often begin where medicine leaves off: at the threshold between science and conscience. Each character is a patient of sorts, carrying invisible wounds that words alone can diagnose. What he observes as a physician, he transforms into narrative – the pulse of compassion rendered in ink.

The invisible thread

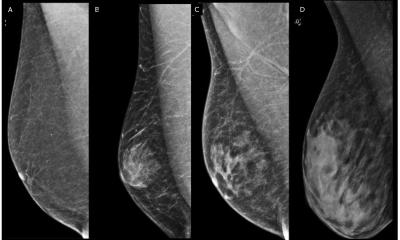

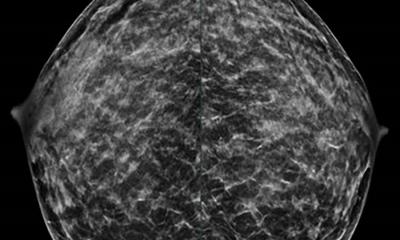

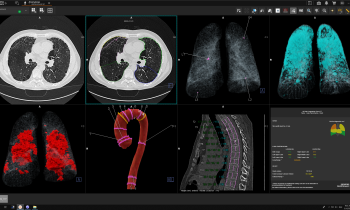

In his Opening Lecture that kickstarted the French radiology meeting, Rufin explored an unexpected analogy: the link between radiology and writing. Both disciplines, he said, are arts of interpretation. Both reveal what cannot be seen directly. ‘Radiologists interpret shadows,’ he reflected. ‘Writers do the same – we make sense of what hides beneath appearances.’

In his view, radiology is not only a technical practice – it is a narrative one. Each scan tells a story of fear, resilience, or recovery, waiting for someone to translate it into meaning. Through that act of interpretation, medicine becomes something more than diagnosis – it becomes understanding.

Between science and spirit

Rufin’s talk flowed like a dialogue between two worlds – that of data and that of humanity. He reminded the audience that science and art are not enemies but allies, sharing the same curiosity about the human condition. ‘Science describes, literature reveals,’ he said. ‘One seeks to heal the body; the other helps heal what the body can’t.’

The more precise our tools become, the more we must protect the human connection that makes healing possible

Jean-Christophe Rufin

For Rufin, the danger of modern medicine lies not in technology itself, but in the forgetting of poetry – when doctors stop seeing their work as an encounter and start seeing it as a procedure. ‘The more precise our tools become,’ he said, ‘the more we must protect the human connection that makes healing possible.’

He spoke of the early days of humanitarian medicine – of doctors who worked without machines, guided only by listening, touch, and intuition. Those experiences, he said, taught him that true healing happens in the space between two beings, long before any prescription or image.

The radiologist as storyteller

As the discussion deepened, Rufin returned to a theme that unites all caregivers – the responsibility of interpretation. Whether doctor or writer, both face the same challenge: to make the invisible legible, without reducing its mystery. ‘Every diagnosis,’ he said softly, ‘is a kind of story. To tell it well, one must see the person, not just the lesion.’

That sentence – part poem, part prescription – seemed to suspend the room in silence. Around him, hundreds of radiologists listened as if reminded of something intimate: that behind every image lies a face, a name, a heartbeat. It was a moment of collective stillness, a shared awareness that radiology, in its essence, is about empathy through vision.

The courage to see

When asked whether he missed practicing medicine, Rufin paused, then smiled: ‘I never left it. I just changed instruments. A pen can reveal as much as a scalpel.’ The audience laughed softly, but the truth of his words lingered. For Rufin, writing remains a form of care – one that dissects human experience with tenderness instead of steel.

He spoke of his younger self, the doctor walking through refugee camps with nothing but gauze, hope, and exhaustion; and of his older self, the writer who still searches for the same thing – a way to understand suffering and give it shape. ‘When you write,’ he said, ‘you heal a little – not only others, but yourself.’

As the session closed, the applause carried both admiration and gratitude. Rufin had not spoken of imaging protocols or artificial intelligence, but of something rarer: the ethics of attention – the act of truly seeing another human being.

In a congress filled with technology, his words offered a kind of radiography of the soul – reminding everyone in the room that beyond the noise of machines, the essence of medicine is still, and always will be, a story.

Profile:

Jean-Christophe Rufin is a French doctor, diplomat, historian and novelist. He is a former president of Action Against Hunger, one of the earliest members of Doctors Without Borders, and a member of the Academy française. After completing his residency in neurology in 1981, mainly at La Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, Rufin became a senior registrar and assistant at Paris hospitals, then an attaché at Paris hospitals. Rufin is one of the pioneers of the humanitarian movement Doctors Without Borders (MSF), where he was drawn to Bernard Kouchner's personality and where he met Claude Malhuret. For MSF, he has led numerous missions in East Africa and Latin America. He has received countless awards for his literary work, notably the Prix Goncourt for first novel for “The Abyssinian” in 1997 and the Prix Goncourt for his historical novel “Brazil Red” in 2001.

04.12.2025