High costs

POCT could lose economic attraction

In addition to physical examinations, medical history laboratory test results are critical in almost all medical decisions made in the hospital. The demand for adequate, fast measurements has increased exponentially over at least the last 50 years and may have increased 100-fold, or more, since the 1950s. This could not have been achieved without the introduction of partial or full automation, of course boosted by the availability of computers and micro devices. Modern, rational healthcare would not be possible without an efficient laboratory service, warns Dr Astrid Petersmann, senior physician at the Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, University of Greifswald, Germany.

Nowadays highly consolidated and complex analysers can run hundreds of different assays simultaneously at a rate of more than one thousand tests per hour. In the modernisation process monotonous, sometimes-dangerous work was eliminated and the precision and relevance of results improved beyond what was thought possible. This has been further emphasised by implementing quality management systems and formalised quality control mechanisms.

Laboratory medicine is responsible for only a comparatively small fraction of healthcare costs and amounts to less than five percent of these. However, the Point of Care Testing (POCT) market has grown much faster than the core laboratory market. Given today’s efficient technology at hand in core laboratories, why has POCT also achieved an immense and accelerating growth in hospitals at the same time as core laboratories grew extremely efficient and highly standardised?

Costs for POCT reagents often exceed costs for core laboratory tests several fold. Investment costs for a single POCT assay systems may seem low but POCT devices are limited to one or few assays only and do not produce a fraction of results during their life cycle compared with instruments in the core laboratory. Additionally, the latter often handle hundreds of different assays. If investment costs were calculated per assay, POCT could lose its economic attraction. The investment costs may be hidden in the reagent costs when pay per use, or pay per patient result, are the basis for financing. Further, the price for a single assay POCT device may be affordable by individual hospital departments and the approval of hospital administration may not be needed. Managing directors might be surprised if they inspect their hospital for all POCTs in use.

Patient safety is a critical issue. In the same hospital, assays offered by the core laboratory and a POCT can be of high quality yet could still lead to discrepancies in results, especially if there is no centrally managed POCT concept. If a patient receives results from both systems during his stay this question will be raised: Which result is the correct one? How can the clinician deal with these discrepancies? What is common knowledge to Laboratory Medicine does not receive a high awareness in other professions among the hospital medical and administration staff: assays may differ systematically and it is not a rare finding, despite worldwide efforts for harmonisation.

An issue affecting economics and patient safety at the same time can be summarised as ‘responsibilities connected to running laboratory test’. Regardless of how easy any POCT is, everyone in the workflow stages needs to be trained. One of the key features of POCT is the number of people involved.

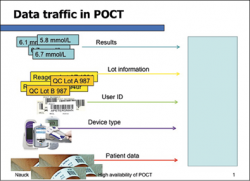

Whereas a core laboratory has a rather limited number of staff, POCTs are often carried out by even thousands of hospital staff members across different healthcare professions. Even if training for one type of device takes a minimum amount of time, it immediately builds up huge demands of time and organising resources, if professionally done. Skills also need to be practised and maintained, or quality will falter. Regardless of whether a test result was obtained from a core laboratory, or a POCT, the same quality standards must be met. Therefore, there can be no compromises in quality assurance and quality management in POCT. Unfortunately, this is not always realised or practiced and imposes risks for patient safety. For instance, if connectivity to the hospital information system is missing, faulty instruments and reagents may be overlooked and create threats to patient safety. Also, the use of analytically poor devices, untrained or unlicensed users might lead to erroneous test results and errors in patient care. By the time thousands of users are involved, the risk of errors increases, bearing immense challenges for any quality management system.

Do the benefits of POCT exceed these risks for patient care and economic efforts? If properly used, certainly yes. Not without reason POCT has a long tradition in patient care. Measurements of blood glucose and blood gas analysis are well-known examples. One common key feature is their immediate impact on patient care that can hardly be achieved by the core laboratories. Even though a few hospitals manage to offer centralised blood gas analyses with the help of fast transport e.g. pneumatic tube systems, most hospitals operate blood gases as a POCT to meet urgent needs in intensive care. An immediately available glucose test result is often crucial in diabetic patients, when insulin dosage depends on it.

When it comes to hospital processes the issue becomes a little more complicated. POCT is thought to improve workflows by cutting short the time a test result from the core laboratory becomes available. Especially in emergency rooms this has become a trend that first focused on a few assays, such as Troponin. Nowadays, the assay menu offered in emergency rooms begins to broaden as suitable and consolidated multiple assay POCT instruments become available.

Some hospitals even create dedicated satellite labs in the emergency room equipped with POCT. If done professionally, this may be of considerable value for patient, hospital and staff. Still, the benefit of POCT on workflow, and consequently on costs, is controversially discussed. Even if theoretical scenarios for the positive impact of POCT on clinical workflows appear promising, sufficient and comprehensive studies are still missing. One reason may be that clinical workflows contain many steps and also depend on human beings. They can only be standardised to a certain extent, which is challenging for the evaluation of economic effects.

How then should POCT be used? Naturally, because both core laboratory tests and POCT are used for patient care in hospitals, they should have the same demands on quality standards. They are both subject to legal requirements, such as the EU-IVD and subsequently many other national and local regulations. To meet those standards POCT uses up more human resources than a core laboratory. These human resources are difficult to estimate and therefore often neglected in justifying a POCT solution. Neglecting the training efforts, maintenance, quality assurance and troubleshooting cost causes an enormous bias in economic considerations. The burden is often imposed upon health care professions, such as nurses or physicians who already are overloaded by tasks that are not directly experienced as related to their respective profession.

There are needs in patient care that can best be met by professionally and centrally managed POCT. Professional POCT management includes IT solutions that go hand in hand with the laboratory and hospital information system and also suitable instruments that fulfil analytical and workflow needs.

With all this in mind, POCT should be used as much as necessary and as little as possible. A point of care testing concept represents a key responsibility that should be inter-disciplinarily developed and centrally decided in each hospital.

PROFILE:

Biologist Astrid Petersmann MD specialises in laboratory medicine and is a senior physician at the Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, University of Greifswald, Germany. She is also a member of the ‘POCT’ working group at The German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (DGKL).

13.01.2016