Nanoparticles

Huge potential, but are there health implications?

EH correspondent David Loshak reports

The rapidly developing discipline of nanotechnology is now the focus of intense scientific research, not least because it could have hundreds of applications in drug delivery, diagnostics, nutriceuticals and biomaterials.

Sadly, however, like most major scientific advances, it poses serious medical and environmental dangers. History is strewn with technologies that initially appeared to be benign but proved to have disastrous effects.

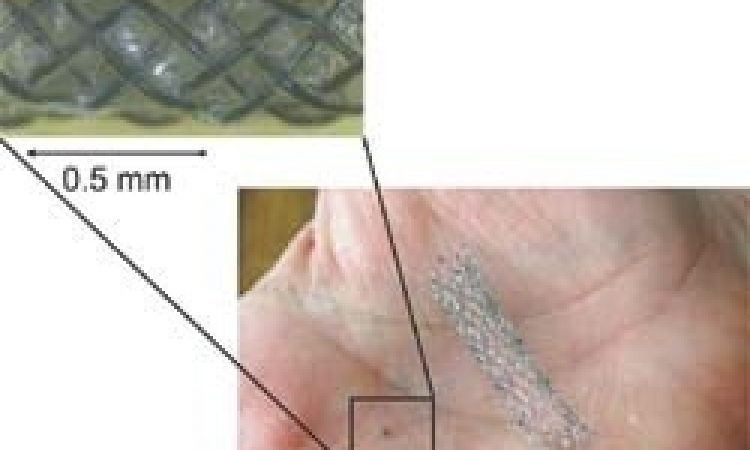

Nanoparticles are less than 100nm. across – a thousandth of the width of a human hair. Despite these minuscule proportions, they are huge in potential.

According to Professor Wolfgang G Kreyling (right), of the Helmholtz Zentrum München Research Centre for Health and Environment in Germany, nanoparticles are attractive because their surface to mass ratio is much larger than that of other particles and materials, which permits catalytic promotion of reactions. It also allows different compounds to be adsorbed – the process by which a layer of atoms or molecules of a substance, usually a gas, is formed on the surface of a solid or liquid.

However, studies have shown that some nanomaterials can damage skin, brain and lung tissue. Because so small, they can be inhaled into the very deepest reaches of the lungs, where they can migrate into the blood and also damage the cardiac and immune systems. The US Centre for Disease Control cites animal studies that have shown that ‘at equivalent mass doses, tested insoluble ultrafine particles are more potent than larger particles of similar composition in causing pulmonary inflammation, tissue damage, and lung tumours. Engineered nanoparticles are likely to have health effects similar to well-characterized ultrafine particles with similar physical and chemical characteristics’.

Prof Kreyling likewise warns that nanoparticles, after inhalation, besides involving inflammatory responses in the lung, with subsequent systemic effects - asbestos provide a disturbing example – threaten to have direct toxicological effects on the central nervous system. ‘The reactivity of the surface can make nanoparticles unpredictable since, immediately after generation, they may have their surface modified.

‘On the one hand, they have a large functional surface, which can bind, adsorb and carry other compounds such as drugs, probes and proteins. On the other hand, nanoparticles might be chemically more reactive than their fine (100 nm) analogues.’

Prof Kreyling points out that nanoparticles have been responsible for increased mortality and morbidity due to environmental particle exposure. ‘Deaths from specific respiratory diseases can increase by as much as 2.7%.’

Despite this, nanoparticles are in medicine to stay because they are crucial for the development of better drugs. As it is, many oral medications are destroyed by the stomach or liver. Their therapeutic potential is hampered by their inability to cross biological obstructions such as the blood-brain barrier and placenta. And, while all have side-effects, some are unacceptably toxic.

Targeted drug-delivery with nanoparticles could overcome such problems, which is why many applications are being developed. There is also the prospect that nanorobots smaller than a cell could transform medicine, with computational genes introduced into the body to detect damage, repair it and overcome infections.

01.03.2009