Article • Smart patch

ELSAH: A wearable to determine biomarkers

The EU four-year project ELSAH, which began at the dawn of 2019, aims to design a wearable to enable continuous determination of biomarker concentrations.

Interview: Sascha Keutel

Project coordinator Dr Joerg Schotter, Molecular Diagnostics, Centre for Health & Bioresources, AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH, explains the project’s objectives and potential applications for the planned wearable.

‘The market for wearables – devices that monitor the fitness status of the user in real time – is growing rapidly,’ Dr Schotter explained. But, he added: ‘These are mainly devices that measure the physiological parameters, such as heartbeat or oxygen saturation in the blood. These wearables cannot determine the molecular biomarkers in biological fluids that are important to obtain a better insight in certain illnesses or health conditions. One problem here is that such analysis requires direct contact with the user’s biofluids, normally blood. However, blood extraction is an invasive technique that is incompatible with the needs of wearable users.

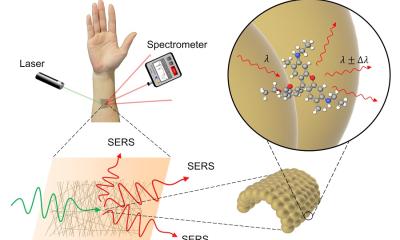

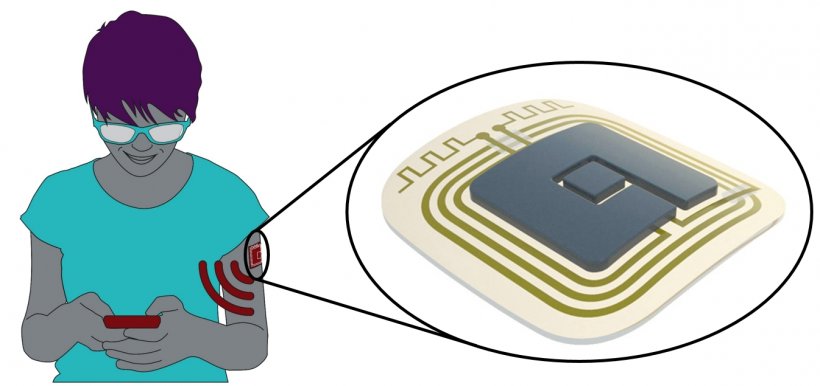

‘To overcome this obstacle, we want to develop an integrated sensor system that can be worn on the body. ELSAH stands for “Electronic smart patch system for wireless monitoring of molecular biomarkers for healthcare and well-being”. Our smart patch ought to determine the concentration of molecular biomarkers in the skin, more precisely the interstitial fluid, in a minimally-invasive fashion.’

For which fields is the patch intended?

The smart patch opens completely new opportunities for use of wearables for evidence-based applications in the health and lifestyle field

Joerg Schotter

‘In the first demonstrations of our patch, we chose glucose and lactose, among the most established biomarkers, to measure a healthy way of life. Lactose has a similar objective to that of athletic watches to determine the user’s training condition. Applying the lactose parameter, hyperacidity of the blood can be controlled and thus the optimum training range determined. By measuring glucose, on the other hand, we can monitor the nutritional condition of the user. This wearable is supposed to support the user in daily decisions for a healthy way of life, for example if this person wants to maintain a certain diet, together with a workout program.

‘The smart patch opens completely new opportunities for use of wearables for evidence-based applications in the health and lifestyle field. Their use can lead to improved health and increased well-being. In the long term, we expect they will also lead indirectly to a reduction in the number of popular illnesses, such as obesity, cardio-vascular illnesses, high blood pressure or type 2 diabetes.

‘At the end of the project period we want to present a demonstrator that we have developed together with our partner, the German Sport University Cologne. This demonstrator is then to be evaluated in a limited user group both in the laboratory and at home monitoring.’

How does this technology work?

‘Currently, a series of wearables have been developed that use non-invasive biofluids, such as sweat, saliva or natural eye fluid. These systems often have to deal with specific challenges, such as poorly defined correlations of biomarker concentrations. ‘Our portable sensor system ought to overcome this problem. The patch comprises micro-needle biosensors, a microchip, printed antennae and a printed battery. The micro-needles can be placed and worn painlessly. A “patch applicator”, a kind of spring, ensures that the patch lies properly on the skin and that the micro-needles are properly placed. The electronics in the patch function autonomously and measures independently; the data is transmitted wirelessly to the appropriate user app.

‘The patch makes wireless transmission of collected data to the user’s app possible and thus permits real- time measurement of both biomarkers. At present, we plan the measurement per patch for 24 hours.’

Are many others involved in the development?

‘The project consortium comprises ten partners from five European countries. Preparation for the measurement of biomarkers in the skin, using micro-needle biosensors, comes from Tony Cass, Professor of Chemical Biology in the Department of Chemistry and Institute of Biomedical Engineering at Imperial College London. Cass has already shown that glucose in the interstitial fluids of the skin is measurable with microneedles and that there is a correlation to the amounts measured in blood. Along with Imperial College London, the German Sport University Cologne and AIT, the research institutes Centro Technológico LEITAT (printing of antennae) and Tyndall National Institute (production of micro-needles) are involved.

‘Our partners from the industry are DirectSens GmbH (development of enzymes for the biosensors), LykonDX GmbH (app development and use), Saralon GmbH (print of batteries) as well as Infineon Technologies Austria AG (manufacture of microchips). Sanmina Ireland Unlimited Company is the partner that takes to the overall integration of the patch. Sanmina will also produce the applicator that enables controlled application of the patch to the skin.’

Profile:

Dr Joerg Schotter joined the Centre for Health & Bioresources at the AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH in 2005, where today he researches new ways and principles to identify and analyse biomolecules. Within this context, he also coordinates the ELSAH project.

Further details: http://www.elsah.researchproject.at/

18.11.2019