Ebola

Anesthesiologists need to 'better educate' themselves

As the Ebola virus disease pandemic unfolded in 2014, it may have seemed like a sudden and unprecedented event. But the disease has a long history, the epidemic is ongoing, and new outbreaks are certain to occur in the future, reports the September issue of Anesthesia & Analgesia.

Especially with recent news of persisting and recurrent Ebola outbreaks in some West African countries, anesthesia providers and other healthcare professionals need to know about the "past and present" of Ebola virus disease, according to a review by Dr. Michael J. Murray of Grand Canyon Anesthesia Consultants, Scottsdale, Ariz. He writes, "We as anesthesiologists should take the necessary steps now to better prepare and educate ourselves so that we can protect our families from the sequelae of such events, and provide effective treatment for those to whom we will provide care during this and subsequent epidemics."

Modern Health Threat with a Long History

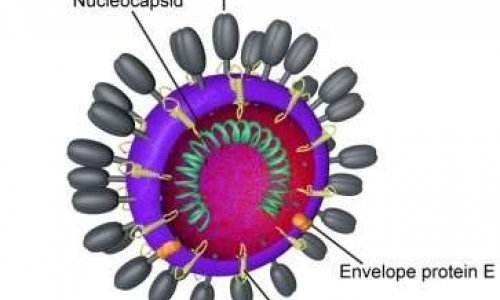

Ebola virus and the related Marburg virus belong to the Filoviridae family of viruses. The first cases of viral hemorrhagic (bleeding) disease caused by Marburg virus were recognized nearly 50 years ago, when European laboratory workers were infected by monkeys imported from Uganda. Two epidemics caused by a virus that proved to be Ebola occurred in Sudan and Zaire during 1976. The disease spread readily, especially with close contact. Stringent infection control and isolation measures were necessary to bring the outbreaks under control. Over the years, more than 20 outbreaks have occurred in Africa, with mortality rates sometimes reaching 100 percent.

After extensive research, fruit bats were identified as the natural reservoir of Ebola virus. The current epidemic likely began with a child in Guinea who had contact with a bat. The disease rapidly spread to other West African countries—among the world's poorest nations, with limited resources to deal with the challenge. "Barriers created by poverty, illiteracy, and distrust impaired efforts to contain the disease," writes Dr. Murray.

With the ease of international air travel, the epidemic quickly became a pandemic affecting three continents. Many Ebola cases in the United States and Europe occurred in healthcare providers exposed to infected patients. In some cases, workers were infected despite personal protective equipment.

Ebola virus spreads through body fluids and direct contact. Although there have been no confirmed cases of aerosolized Ebola transmission to humans, this remains a "justifiable concern," according to Dr. Murray. He reviews the pathophysiology by which Ebola virus is transmitted and causes disease. Early infection may block key immune functions, allowing the virus to disseminate throughout the infected organism.

The disease doses not become contagious until fever and other symptoms appear, after an incubation period ranging from two to 21 days. Symptom criteria for diagnosing Ebola virus disease have been established; confirmatory tests must be performed at a biosafety level-4 facility. There no known treatment, and little is known about how the disease leads to fatal shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation (widespread clotting).

While the Ebola epidemic has largely dropped out of the headlines, the World Health Organization continues to report new cases in Sierra Leone and Guinea. Recently, the epidemic recurred in in Liberia, where it had previously been considered under control. "The current Ebola virus disease pandemic has lasted longer, affected more individuals, killed more patients, and created more social havoc than all previous Ebola virus disease epidemics combined," Dr. Murray writes. He emphasizes that the outbreak occurred not because the virus mutated, but because of lack of information, inadequate public health practices, ease of travel, insufficient infection control, and poor healthcare education.

Potentially effective treatments are under development, including use of serum from convalescent patients, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines. But Dr. Murray emphasizes that the Ebola outbreak will ultimately be brought under control using the techniques and methods proven effective in past epidemics: early diagnosis, allowing patients to be quickly isolated; contact tracing to identify other people who may have been exposed; and "strict (and better) infection control procedures."

Source: International Anesthesia Research Society

28.08.2015