Article • White matter

Age-appropriate disease? Doesn’t exist

What can we learn from population studies? According to Gabriel Krestin MD PhD there are things that we can un-learn, as well as learn, from population imaging studies.

Interview: Daniela Zimmermann

The Chair of the department of radiology & nuclear medicine at Erasmus University Medical Centre, Krestin also leads the European Population Imaging Infrastructure (EPI2), an initiative of the Dutch Federation of University Medical Centres and Erasmus University.

Population imaging is the large-scale application and analysis of medical images to find imaging biomarkers that enable the prediction and early diagnosis of diseases. The EPI2 coordinates data acquisition at diverse locations and times and is a flagship node of the Euro-BioImaging initiative, one of the large distributed life-sciences infrastructures on the European Strategy Forum for Research Infrastructures Roadmap. Pan-European participants include radiologists and research organisations from Austria, Finland, France Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

At the Garmisch MR 2017 Symposium, held in January, Krestin focused on brain imaging in the Rotterdam Scan Study to challenge the widely held concept that there is an age-appropriate approach in medicine. ‘There is no such thing,’ he stated during our EH interview, defying this largely accepted idea in what he acknowledges is a provocative talk.

‘In the past the term “age-appropriate” has been used to relate a lot of alterations to the process of aging. The changes that we attributed to age are, in fact, caused by symptomatic and sometimes pre-clinical or asymptomatic disease. Aging is not a so-called normal process. There is no such thing as a normal aging of the brain. It is not normal that you lose or deteriorate in your brain function with age, that the brain becomes senile.

‘What we see is the influence of many external factors, many risk factors, many related diseases, or perhaps of genetic predispositions. But it’s not necessarily the number of years you have lived that lead to these changes.

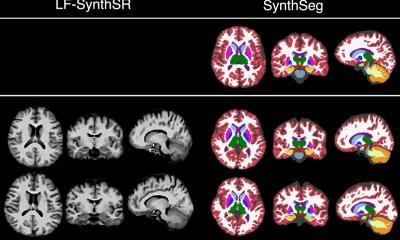

‘In population studies, when we started we were looking for very simple things, such as the different volumes of the brain across subjects of different ages. We were taught in medical school that, after adolescence, the number of neurons in the human brain is decreasing with age. Yet, when we were looking at volumes of brain structures, measuring grey and white matter, what we saw was that, with increasing age, the grey matter is not changing in volume. It’s the white matter that changes in volume. If we look deeper we find that it is not the grey matter that atrophies so much as the white matter.’

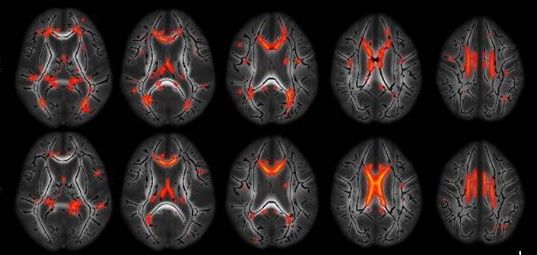

‘Another process that we relate to age is the formation of white matter lesions. With some sequences in MRI we can identify those small, high-signal intensities, even if we don’t know exactly the histopathology and pathophysiology of these lesions.

‘We assume that these white matter lesions are related to degeneration, and at the same time, we know that the number and the load of white matter lesions increase with age.

‘From population imaging studies we learned that white matter lesions are associated with a certain number of risk factors. For instance cardiovascular risk factors, like smoking, hypertension, or diabetes, lead to an increased white matter lesion load. And, finally, we also learned that these white matter lesions are also predictors of certain outcomes, of dementia, but also of stroke.

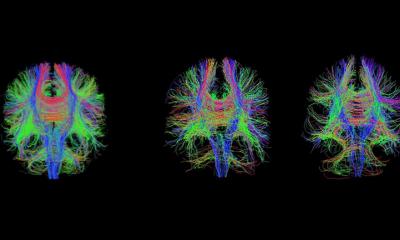

‘Still, all of this is only the tip of the iceberg. There’s a lot more that we cannot see with our eyes that are under the water line, let’s say. Today we can measure with sensitive tools such as diffusion weighted MRI, the microstructural integrity or damage of the white matter. With these measures, what we find in longitudinal population studies is that even in the non-affected white matter, which appears to be completely normal on conventional MRI images, a change in these diffusion metrics appears long before the white matter lesion becomes visible – years later. On the other hand the microstructure of the white matter is linked to cognition, and damage is associated with impairment of cognition.

‘We have also done functional connectivity studies and we can see these white matter damages that we attributed to aging are quite extensive. Yet they have nothing to do with age. When we correct for all the risk factors, and a lot of other factors that can play a role, we see that there’s not much remaining. Instead of a change with age these aging people are increasingly affected by other diseases or impairments related to cardiovascular risk factors, diabetes, decrease of brain perfusion or impaired microvasculature.

‘Again, my message is that what we relate to age is not, in fact, due to the so-called normal aging process but is part of a process that has to do with some disease pathophysiology.

‘The reason that assessment of such imaging alterations becomes important is that these measures are biomarkers that can predict certain outcomes. People who have damage to the microstructure of the white matter, or show a high level of atrophy, or white matter lesions, will have a higher risk to develop dementia or stroke.

‘Over the past fifty, years we have increased life expectancy due to the fact that today we have a much better understanding of these risk factors and thus a better prevention, by decreasing the number of predisposing or external factors.’

Profile:

Professor of Radiology Gabriel P Krestin chairs the radiology and nuclear medicine department at Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. A graduate of the University of Cologne, Germany, his residency in radiology was completed in 1988. He was later appointed radiologist and head of the MRI Centre in Zürich University Hospital, Switzerland, where he became associate professor of radiology and head of the clinical radiology service, before moving to his present Position.

02.03.2017