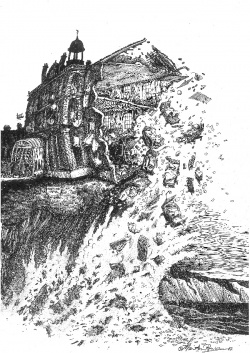

Acute hospital care in England could be on the verge of collapse

Around 65% of in-patients are over 65 years old

With growing bed shortages and increased demand on clinical services, the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) says that the country’s National Health Service (NHS) is approaching the point where acute care cannot keep pace in its current form, Mark Nicholls reports

Figures contained in the college’s hard-hitting report ‘Hospitals on the edge?’ show there are a third fewer general and acute beds in the NHS today than there were 25 years ago, but there has been a 37% rise in admissions over the last decade.

According to RCP President Sir Richard Thompson, ‘It is difficult to measure how close we are to collapse but a lot of hospitals are only just managing at the moment so any major unforeseen emergency could tip them over the edge and see them close to acute admissions.’

Treating patients with dignity

The fall in bed numbers is coupled with more older people being admitted to hospital. Some 65% of people admitted are aged over 65, with a significant number over 85. An increasing number are frail with hospital buildings, services and staff often not equipped to deal with people with multiple, complex needs including dementia, diabetes, stroke and urinary tract infections.

‘It is a very complex mix of patients coming in,’ Sir Richard explained. ‘We do not have a good social care structure out in the community, nor good primary care, so these patients come into hospital because there is nowhere else for them to be looked after.

‘We have noticed the situation getting worse, year on year. The number of A&E attendances and admissions to acute beds goes up each year, while there has been a continuing reduction of acute beds across the country.

That progressive reduction has been to save money with the hope that better community care will reduce admissions but at the moment it is not doing that.’

A survey of RCP members showed their biggest concern was a lack of continuity of care with hospitals particularly failing to look after patients properly at evenings and weekends. It is not uncommon for patients, particularly older patients, to be moved four or five times during a hospital stay because of a shortage of beds and often with incomplete notes and no formal handover.

‘As a medical profession we have to look at how we are handling acute patients in the hospital - the fact so many are moved beds at night or having blood tests at night is appalling and that is the sort of thing we are going to have to resolve,’ he added.

Additionally, the RCP report said that hospital staff often see the elderly as ‘unwelcome’ and think they ‘shouldn’t be there’, even though they make up two thirds of patients. ‘One doctor told me that his Trust does not function well at night or at the weekend and he is ‘relieved’ that nothing catastrophic has happened when he arrives at work on Monday morning,’ Sir Richard said. ‘This is no way to run a health service. Excellent care must be available to patients at all times of the day and night. We call on government, the medical profession and the wider NHS to work together to address these problems.’

To help tackle the looming crisis, the RCP is calling for: all health professionals to promote patientcentred care and to treat all patients with dignity at all times; the redesign of services to better meet patients’ needs with planning and implementation of new services clinically led; re-organisation of hospital care so that patients can access expert services seven days a week; and access to primary care to be improved so that patients can see their GP out of hours, relieving pressure on A&E services.

More money is no answer

The report said there should be a concentration of hospital services in fewer, larger sites that are able to provide excellent care round-the-clock and improvements in community services to avoid many patients ending up in hospital because of a lack of help close to home. To examine better processes and standards for treating medical patients, the RCP has established the Future Hospital Commission (FHC), which will report in a few months’ time. The RCP report, which plays a leading role in the delivery of high quality patient care by setting standards of medical practice and promoting clinical excellence and represents over 27,500 fellows and members worldwide, coincides with a period that the NHS is under severe pressure to make financial savings amounting to billions of euros. However, Sir Richard said making more money available was not the only answer and he believes that junior hospital doctors’ hours should be relaxed to help with more flexibility within rotas and with continuity of care, which is currently ‘very poor’. He also wants to see a new cadre of generalists appointed in hospitals to provide the continuity of care, as well as more physician assistants.

Struggling with age and complexity

If action is not taken soon, he said, ‘I think there will be a continued flight of doctors from this area of medicine because they are finding the strain very high and some are disillusioned. In addition, hospitals will be closing to acute admissions at times because they will not be able to cope. It is very serious.’ Professor Tim Evans, one of the report’s authors and also an intensive care consultant at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London, added: ‘It’s increasingly clear that our hospitals are struggling to cope with the challenge of an ageing population with multiple, complex diseases’, and he warned that if steps were not taken to improve hospitals, there may be other scandals, such as that which occurred at Mid-Staffordshire NHS trust, where hundreds of patients died due to poor care between 2005 and 2009.

Profile:

Having served as treasurer of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) from 2003, Sir Richard Thompson became its President in 2010, a role in which he leads the organisation on behalf of its fellows and members. Following his training in natural sciences and medicine at Oxford and St Thomas’ Hospital Medical School, and junior posts in London, he joined Dr Roger Williams in the early days of the liver unit at King’s College Hospital, and spent 18 months with Professor Alan Hofmann at the Mayo Clinic. He became a physician and gastroenterologist at St Thomas’ Hospital in 1972, serving until his retirement in 2005. For over 30 years he also led a clinical research laboratory, chiefly studying aspects of nutritional gastroenterology, and had also supervised 30 MD and PhD theses as well as publishing over 200 papers and, during 21 years of his career, Sir Richard also served as physician to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

09.11.2012